During the Advent season, we bring you an inspirational piece of Renaissance music that is based on a quote from St. John’s gospel. Nearly five hundred years old, this hymn has a timeless beauty that will be a gift to our world for as long as there are voices to sing it. But first a little background.

If you are familiar with Gregorian chant, you know that its form is essentially a single line of music with voices singing in unison. It is the familiar religious music of monks and nuns in their monasteries. (I’m sure its sound echoing off chapel walls is also the origin the word “enchanting”!)

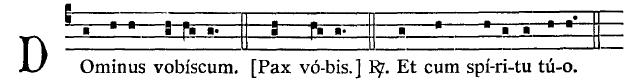

Here is a graphic representation of one line of simple Gregorian chant (tr. “The Lord be with you. [Peace be with you.] And with your spirit.”):

Chant blossoms

But Gregorian chant, for all its sublimity, blossomed into another type of music in the Renaissance era. For the sake of illustration, allow me an oversimplification here. Sometimes in my imagination I wonder what it must have been like for the first monk to miss his cue and mistakenly sing two notes above the other chanting voices.

“Hey, that sounds kinda nice!” he might have said when he heard the effects of his mistake. Then, some other daring monk decided to sing two notes above that to see what it sounded like and, lo and behold, three-note harmony was born!

“A three-ply cord is not easily broken,” says the Book of Ecclesiastes (4:12), and the term, in English at least, describes perfectly the phenomenon we call a musical “chord”, which is what results when two or more voices (or instruments) join together to create a single complex tone.

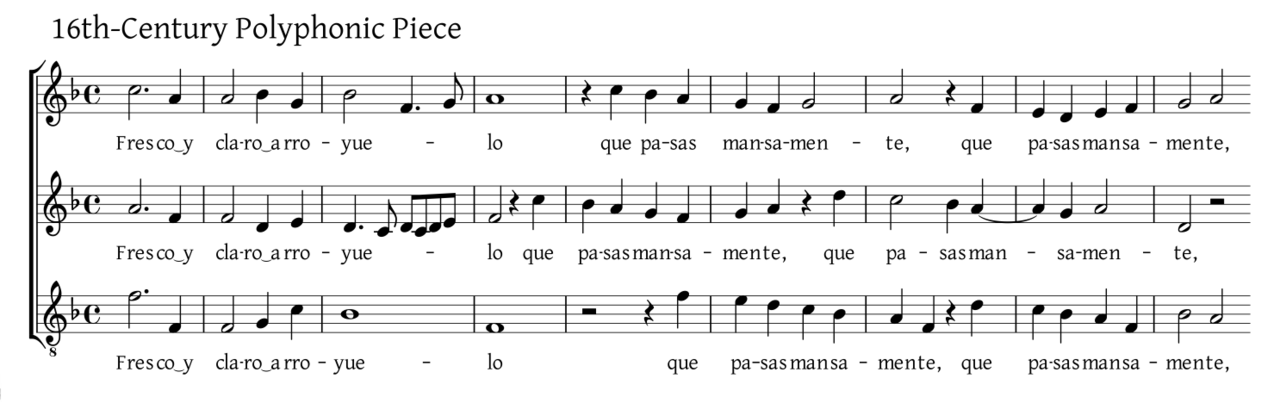

In musical terminology, this type of singing is called “polyphony” (accent over the middle “y”) as distinct from chanting or unison singing. Here is an example of polyphony:

As I say, for the sake of illustration I have oversimplified a musical phenomenon that is probably very ancient in human history and developed over many centuries in Western culture. However, we can roughly date the advent of church polyphony to about the late Middle Ages (13th century) and its flourishing in the Renaissance (14th-16th centuries).

Thomas Tallis

One of the preeminent English polyphonists is Thomas Tallis, whose spectacular work, “If Ye Love Me” (1565), is the subject of this post. Tallis was a dedicated Catholic whose music thrived despite the persecution of Catholics during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (reigned, 1558-1603). He grew up during the reign of Elizabeth’s father, Henry VIII, and performed for four different English monarchs during his long lifetime (1505-1585) which spanned the entire tumultuous 16th century in England.

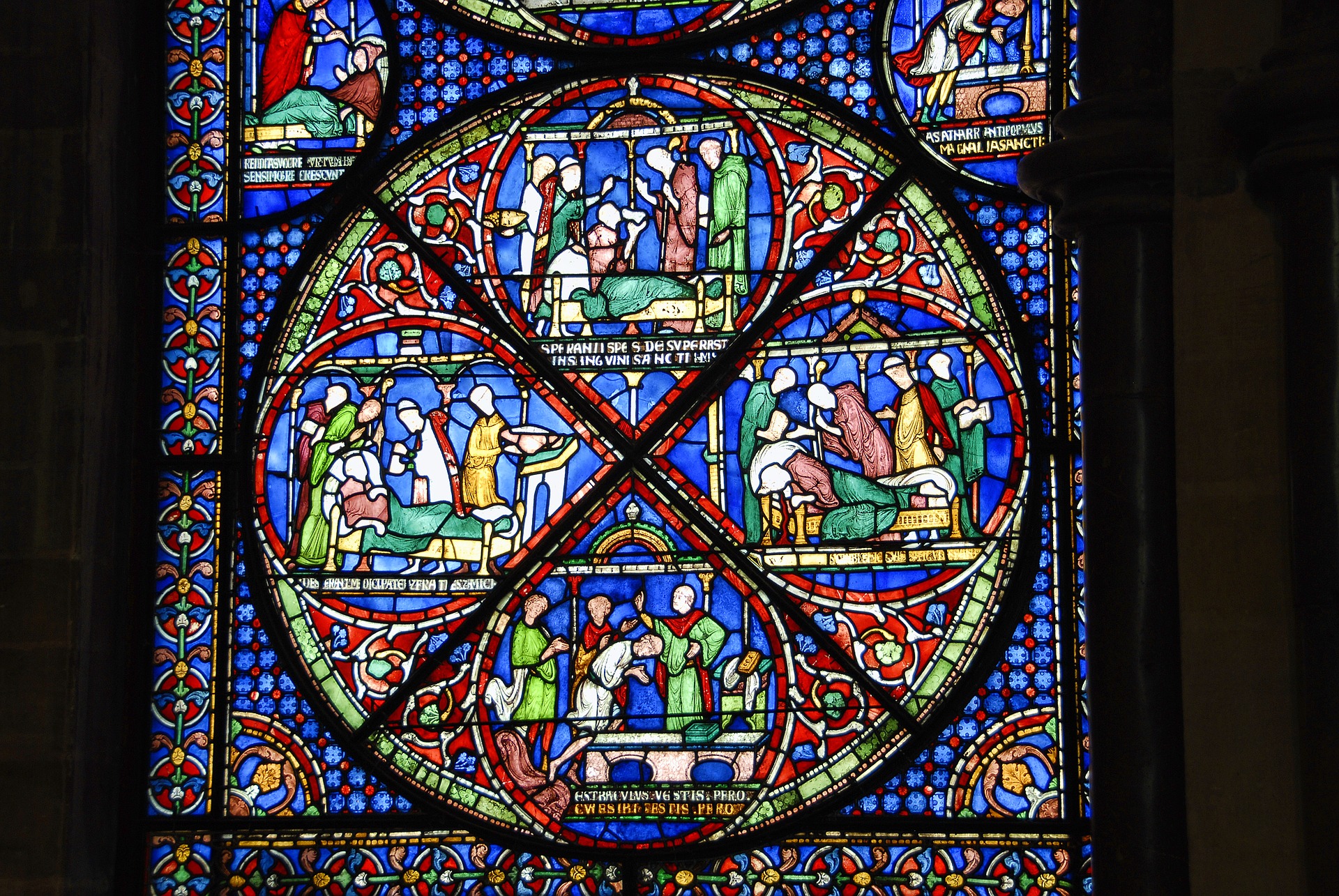

(By the way, the featured image above is a stained glass window from Canterbury Cathedral in Kent, England where Tallis was choirmaster and chief musician for most of his career.)

Listening to his music, however, you would not imagine that he composed his angelic polyphony in a time of such turbulence. The piece you will hear in the video below is clearly the most popular of Tallis’s works. It is sublime worship. It is technical perfection and beauty itself.

The piece has such stature in English (Anglican) choral tradition that it was performed for Pope Benedict XVI on his visit to England in 2010 and for Meghan and Harry’s wedding in 2018. One wonders what Thomas Tallis would have thought about the latter, but we’ll leave that one in the realm of speculation.

Before you listen

A few brief notes may help you deepen your understanding of “If Ye Love Me” as you listen:

- It is a religious hymn, technically known as a motet for four voices, which was a distinct style of polyphonic voice music during the Renaissance and beyond. Motets during this period were sung a capella, that is, without instrumental accompaniment.

- As noted at the beginning, the lyrics are a passage from the Gospel of John (14:15-17) taken from William Tyndale’s English translation of the bible. The wording feels a bit archaic, but it is completely understandable to our modern ears. The word “Ye” in the title is the poetic version of “You” plural.

- King Edward VI (reigned, 1547-1553) had encouraged the composition of hymns in the English language rather than Latin. He wanted hymns that the common people could sing, clarifying that the composers of sacred music were to adhere to his one stated principle: “to each syllable a plain and distinct note”. You will notice this principle in the two-syllable words “spirit” (shortened to spir’t), “even” (e’en) and “abide” (‘bide), all of which fulfill the king’s wish perfectly.

- The motet resembles a very elaborate form of the type of song most of us sang as children: the round. The song begins with everyone singing together but then breaks into staggered, overlapping parts which all eventually converge and merge at the end on the same note as it began – forming a perfect circle. (Hence the name “round”.) In this case, the voices interlace with each other throughout the performance like fine strands of colorful thread weaving a tapestry of sound and sublime, worshipful feeling.

I have placed two versions of the same performance side by side for your viewing choice. The first is set to a visual background taken from the final scene of the 1940 Disney animated film, Fantasia, while the second displays the actual musical score so that you can see with your own eyes the almost mystical interlacing of the voices, if that is something that interests you.

After you’ve listened to the performance, I’ll offer one final reflection before our Soul Work section – enjoy!

The performances (duration, 2:09 and 2:26)

Final “note”

The Renaissance was not the age of virtuoso singers such as England would see in the Baroque era 150-200 years later (Handel’s oratorio, The Messiah, is a perfect example of this).

Renaissance church music was still essentially choral music, the production of a community of human voices, which is why John Rutter’s Cambridge Singers are perfectly suited for this amazing performance. As we’ve seen before, Rutter’s work is second to none.

Perhaps because of its choral sophistication, lacking solo voices, this motet is highly unified and integrated. The strands of intertwined voices are not independent of each other but form a whole piece. You cannot remove any one voice part without diminishing, even undoing, the whole piece because it is a single, complete work of inspirational art.

Certainly we owe a great debt of gratitude to Thomas Tallis, a man who dedicated his whole life and career to filling souls with musical grace and peace.

Soul Work

Sublime beauty is an oasis for the soul, and we should take refuge periodically from the hustle and bustle of life in pieces like “If Ye Love Me”.

Yet always keep in mind that the key to this beauty is not individual performance. It is the work of a team, a chorus. Tallis’s original musicians were probably simple parish choristers who gave their talents to others for the sake of participating in a communal act of worship.

We cannot survive in life without teams and groups of like-minded people dedicated to helping others. The self-made man is a myth of Hollywood.

Are you a member of any team? Do you have companions in a holy work or some group of close associates who encourage you to give your best for others? Your talents are more effective when you give them side-by-side with other people who join in the giving.

Focus on your team today and re-dedicate yourself to your generous offering of self so that others can benefit from your selfless work.

Leave A Comment