When you say the word “vault”, most people would assume you’re referring to a gymnastics event or perhaps a form of bank security. But if you were in England, people of a religious bent might actually think you were talking about something very different: the ceiling of a church, or more specifically, the ceilings of their greatest cathedrals and abbeys.

It’s impossible for me to do an adequate survey of the marvels of English Gothic architecture because it is too complex and wondrous to do them justice in one short article. But they are sacred windows into heaven in a very literal way, so for now, I’ll just make a few observations with a focus on the marvelous ceilings.

Drawing the Eye Upward

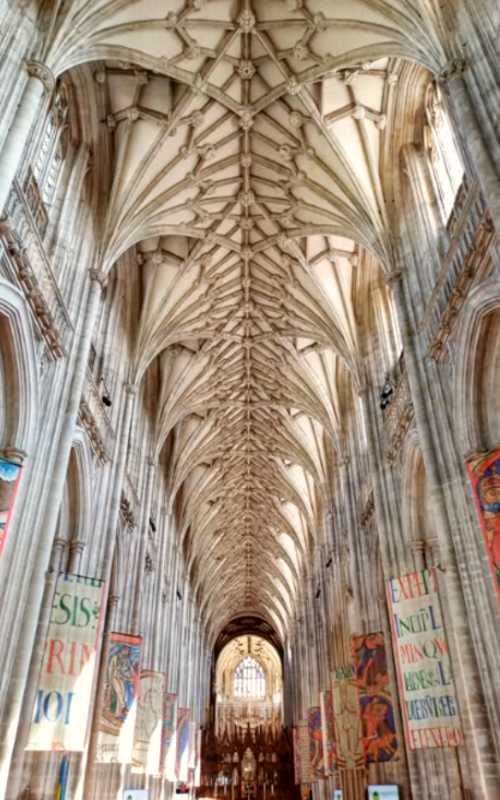

The purpose of a Gothic cathedral, with its pointed arches and soaring columns, is simply to draw the eye—and the heart—upward in a reverent attitude of wonder and prayer. They are the greatest gifts of the medieval period, an age of almost universal Christian faith in Europe.

The ceilings of these magnificent cathedrals will give you a good idea of what I mean about “upward” motion. The very first movement of the observer’s eyes when he enters this space is undoubtedly upward, and his very first word upon seeing them is usually “Wow!”

Westminster Abbey

Carlisle Cathedral

York Minster

Extraordinary Accomplishments

In 1989, the famous British author, Ken Follett, wrote an amazing historical novel called The Pillars of the Earth in which he details the long and intricate process of a community that built a medieval cathedral over the space of some fifty years.

That something could take half a century to build is mystifying to us in the modern age who are used to buildings going up in short order. Even the 102-story Empire State Building in NYC only took a year to build (March 1930-April 1931)! Here is what Follett says about these medieval marvels:

The building of the medieval cathedrals is an astonishing European phenomenon. The builders had no power tools, they did not understand the mathematics of structural engineering, and they were poor: the richest of princes did not live as well as, say, a prisoner in a modern jail. Yet they put up the most beautiful buildings that have ever existed, and they built them so well that they are still here, hundreds of years later, for us to study and marvel at. (Intro, xiv-xv)

He is right. “Astonishing” is probably the only word that can adequately describe the phenomenon of one of these churches.

I can’t help repeating here my favorite quote from historian Paul Johnson who said that “The medieval cathedrals of Europe – there are over a hundred of them – are the greatest accomplishments of humanity in the whole theater of art” (emphasis added).

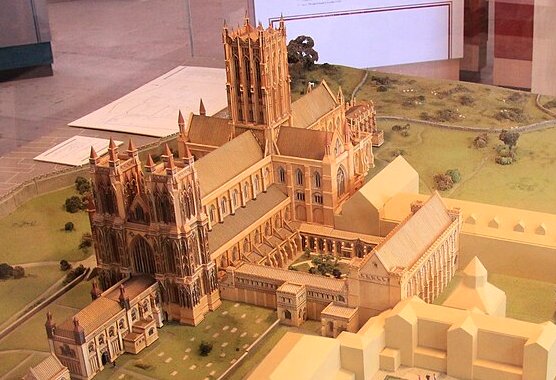

Worcester Cathedral

A Gift of the French?

As I noted in a previous article, Gothic architecture originated in France in the 11th century, but it quickly spread throughout Europe. Cathedral building in the Gothic style was met with immediate enthusiasm once it spread to England.

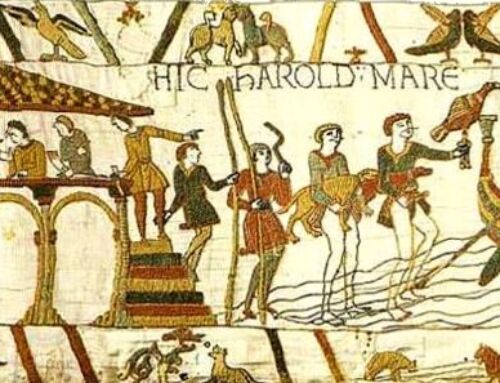

Virtually all of these cathedrals were built from existing churches prior to the Battle of Hastings in 1066 AD. They were Romanesque in style. The earlier churches had round arches, very little window space, and thick walls. Since William the Conqueror was French, maybe he brought the Gothic idea with him!

The starting dates of a few of the largest English cathedrals seem to reflect that idea and show a kind of “holy competition” for glory taking place in the religious culture of Medieval England from that point on:

Winchester (1079) | Coventry (1102) | Ely (1110) | Wells (1180) | Lincoln (1192) | Salisbury (1220) | York (1220) | Gloucester (1327), and many more.

Remember that these were just the starting dates of the respective building campaigns. Due to wars, financing problems, aristocratic infighting, social strife, even the Black Death, many of them took literally hundreds of years to achieve the final form we see them in today.

And some of them, such as Coventry and Westminster Abbey were almost completely destroyed by Hitler in the Blitzkrieg of the Second World War. The latter was wholly rebuilt according to the medieval plans. Amazing!

We must also keep in mind that these were the massive building projects of communities of faith, not corporations. These communities (usually whole regions) marshalled all the skilled resources and money for the task and persisted for three, sometimes four, successive generations or more in watching “their” cathedral rise slowly from the earth. They are, in a word, nearly miraculous expressions of the Church’s common faith.

Peculiarly English

The Gothic style, generally, is characterized by pointed arches, stained glass windows, and high, thin walls (usually bolstered by flying buttresses on the outside). A good number of the English cathedrals retain these characteristics while also giving the architectural style its own unique English flair, such as:

Towers

If the French crafted exquisite spires pointing to heaven, the English did so with square towers that might be mistaken for battlements of the Church Militant.

I particularly love the pinnacled towers that jut upward so powerfully from the roofs of English cathedrals. It’s easy to see where Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, and the cinematic artists of the LOTR movie series, got their inspiration. York Minster (center picture) may be the coolest example of this feature, but it is by no means the only one.

I particularly love the pinnacled towers that jut upward so powerfully from the roofs of English cathedrals. It’s easy to see where Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, and the cinematic artists of the LOTR movie series, got their inspiration. York Minster (center picture) may be the coolest example of this feature, but it is by no means the only one.

And by the way, when a cathedral is called Minster, it always means that it was the church of a religious order or contained the houses for a community of monks. Minster is from the Old English word “mynster”, the equivalent of “monastery”.

Broad Facades

Likewise, the French style was to make their cathedrals comparatively narrow, even if the tower had balancing spires on either side. This is definitely the case with many of the Gothic revival cathedrals built in the US in the mid-to-late 1800s, such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan.

Likewise, the French style was to make their cathedrals comparatively narrow, even if the tower had balancing spires on either side. This is definitely the case with many of the Gothic revival cathedrals built in the US in the mid-to-late 1800s, such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan.

The English, on the other hand, tended to broaden the facades of their cathedrals to massive proportions. Whereas, from the French style, one gets a feeling of light and delicate vertical movement, the English façade leaves one with the sense of imposing grandeur, strength, and maybe God’s wide embrace of the human community. It would not be wrong to describe them with a good British adjective: stout.

My favorite broad façade by far is Lincoln Cathedral (last picture), which is one of those jewels that seems to have all the right facets and accessories. It is also the place where one of the original copies of the Magna Carta is on display because the 13th century bishop of Lincoln was one of the signatories. How about that?

Salisbury Cathedral

Rochester Cathedral

Peterborough Cathedral

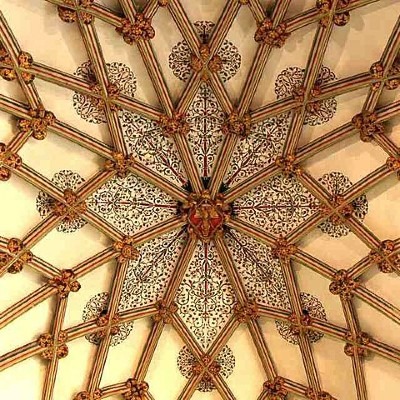

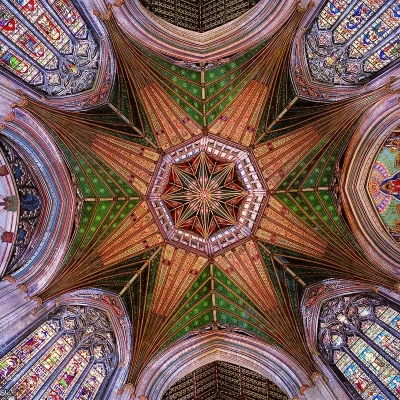

The Vaults

But let’s not get too far afield from our main topic: the ceilings (vaults). They come in various flavors and are simply marvelous. The ceiling designs, of course, are deeply interwoven with the structural design. You can’t have a nice roof unless there is something to keep it from falling in on you!

In the imagery below you’ll see the delicate interplay of pillars, columns, windows, and stone ribbing with the incredible roofs and chapels they hold up. After the structural questions are solved, the English add their own accents and bits of pageantry to make sure you know they’re English and not French or German!

In order not to weigh down my review of these works of grace and art with too many words, I’ll conclude with a summary note at the end after you’ve gotten your fill of these architectural masterpieces, offered in no particular order.

More Fabulous Central Naves

Litchfield Cathedral

Bath Abbey

Wells Cathedral

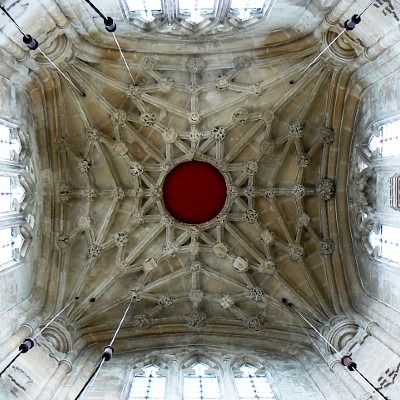

Gazing Up Into The Towers

St. Samson’s Church

Wells Lady Chapel

Winchester Cathedral

Bath Abbey

Beverly Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral

Chapels and Cloisters

Gloucester Cathedral Cloisters

Oxford Divinity School

Westminster Abbey

York Minster Chapter House

Tewksbury Abbey

The Grande Dame of English Vaults

Ely Cathedral

The Only Downside

Perhaps the only sour note in the grand symphony of English Gothic is that all these magnificent churches, built by Catholics, were stolen by Henry VIII and his band of marauding aristocrats in the decade-and-a-half after the Act of Supremacy (1534) by which Parliament made Henry VIII the head of the Church in England.

The destruction that followed was called the Dissolution (or Suppression) of the Monasteries and is easily history’s greatest single act of theft.

It is said that some 12,000 priests, monks, and nuns were made homeless overnight and deprived of their rights to worship. Some abbeys and churches, such as the famous Glastonbury Abbey, were literally dismantled to use their elegant carved stones for building aristocratic manor houses. (Glastonbury was the location of the tomb of King Arthur, now lost.)

The before and after pictures of Glastonbury will give you an idea of the scale of destruction carried out by Henry VIII’s thugs.

It’s a sad tale for sure but one with a glimmer of hope. The vast majority of these ancient monuments of faith were not destroyed and remain in the hands of communities that maintain them and keep them open for prayer and worship. Their architectural genius and beauty still gives witness to Christ on a grand scale, and for that we are grateful.

It reminds me of the words of St. Paul when he wrote to the Philippians about “rivals” who were preaching in competition with him while he was in prison. The great Apostle had the right perspective, as always:

“What difference does it make, as long as in every way, whether in pretense or in truth, Christ is being proclaimed? And in that I rejoice” (Phil 1:18).

Amen! And so do all who look upon the splendor of these amazing vaults.

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 5/18/25. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

———-

Photo Credits: Via Wikimedia and other sources: William the Conqueror (Bayeaux Tapestry): Bath Vault (Deyemi Akande); St Sampson Church Vault (Brian Robert Marshall); Tewksbury Abbey (Bs0u10e01); by Photographer Dillif (Carlisle; Worcester; Bath Abbey Nave; Peterborough; York Minster Nave and Chapter House); Westminster Henry VII Chapel (Herry Lawford); Kings College Divinity School Chapel (Facebook: UK Ancient Cathedrals, Church, Abbeys, and Priories Page); Wells Lady Chapel Vault (Mattana); Glouchester Cloisters (Christopher JT Cherrington); Glastonbury Model (Karl Gruber); Glastonbury Ruins (Nessy-Pic); Ely Cathedral: Lantern (Tilman2007); Feature picture of sunrise (ARelton9); Vault (Trip Advisor: Sofia M); Lincoln façade (DrMoschi); Salisbury Front (Diego Delso); Canterbury Vault (Tobiasvonderhaar); Rochester (2006SweepsCath1); York Tower (Peter K Burian); St Patrick’s NYC (MoTabChoir01).

Leave A Comment