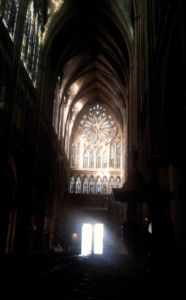

I have never kept my love of Gothic architecture a secret. I have only to walk into a Gothic cathedral to experience a spiritual retreat. I can literally spend hours  looking upward. And there is a good reason for that.

looking upward. And there is a good reason for that.

Gothic architecture is not a bunch of stones placed cleverly together for dramatic effect. It is, rather, an eloquent story to be read and absorbed by the human soul. Best of all, you don’t need a college degree to “read” that story in stone. You can be totally illiterate and still understand the meaning as well as any Oxford don.

That’s because Gothic structures were made for uneducated people in an age before the time of high literacy. The elegant stories they tell are not abstract. They are instructional: their stones tell us how to worship.

The Marvelous Work of a Whole Civilization

The first thing to realize about Gothic architecture is that it is the product of a profoundly Catholic civilization. The men who built these churches were by all accounts fervent believers who also had immense artistic and practical talent.

I noted in a previous newsletter that there is no necessary connection between faith and religious art, yet, when deep faith and art do coincide, the resulting works are usually extraordinarily beautiful.

That is undoubtedly the case with Gothic architecture, which emerged from the completely Christianized society of the Middle Ages.

That is undoubtedly the case with Gothic architecture, which emerged from the completely Christianized society of the Middle Ages.

The majority of the cathedrals I will highlight below were begun in the century beginning around 1150 AD, and it almost defies belief that one age could produce so many enormous blessings for the world.

My favorite historian, Paul Johnson, had this to say about these mammoth creations:

The medieval cathedrals of Europe – there are over a hundred of them – are the greatest accomplishments of humanity in the whole theater of art (emphasis added.) They are total art on the grandest scale, encompassing architecture at its highest pitch, and virtually every kind of artistic activity, from carpentry to painting…. An entire lifetime can be profitably spent in visiting cathedrals and in the minute examination of their beauties and treasures. (Art: A New History, 2003)

Johnson goes on to say that the durability of these structures is also part of their wonder. No one worships the gods in the Roman Pantheon any more, but Christians still worship the One, True, God in all of the ancient cathedrals of Europe!

The Name and Origin

Believe it or not, the name Gothic was not originally meant as a description of a sublime architectural style as we are accustomed to understanding it. “Gothic” was actually meant as an insult. Unfortunately, we only have Catholics to blame for this.

Believe it or not, the name Gothic was not originally meant as a description of a sublime architectural style as we are accustomed to understanding it. “Gothic” was actually meant as an insult. Unfortunately, we only have Catholics to blame for this.

The Italians of the Renaissance (1400s to 1500s) wanted to exalt their own style of architecture (called Romanesque) as superior to all others, so they disparaged the dominant earlier architectural style that was the main rival of their beauty. (Those Italians!) St. Peter’s Basilica is a pretty good example of the Romanesque style.

Yet, in their enthusiasm to denigrate, the Italians also got their facts wrong. They somehow thought the Gothic style was German (where the barbarian Goths came from), so they hoped to brand it as northern, cold, crude, barbaric, and uncultured. Ha!

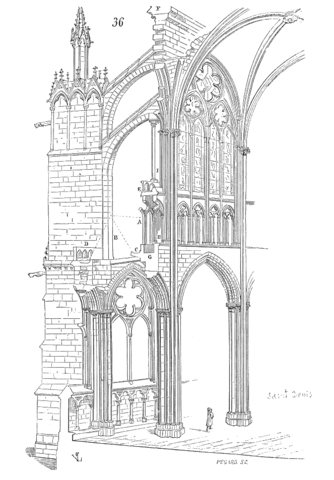

But how could they have overlooked the fact that Gothic was French in origin?! The concept of the Gothic architecture developed from the design of Abbot Suger (pron. Soo-Zhay, 1081-1150 AD), who created the first grand basilica to incorporate all the elements of the Gothic style in the Abbey of St. Denis just outside of Paris.

But how could they have overlooked the fact that Gothic was French in origin?! The concept of the Gothic architecture developed from the design of Abbot Suger (pron. Soo-Zhay, 1081-1150 AD), who created the first grand basilica to incorporate all the elements of the Gothic style in the Abbey of St. Denis just outside of Paris.

From there, the Gothic style spread rapidly throughout Paris and northern France, and within a century there were hundreds of Gothic churches small and large in France. Then, of course, it spread to many other countries of Europe (including Germany!)

English Gothic is as much of a wonder as French Gothic and deserves its own special treatment—stay tuned.

The Most Essential Feature

If you were to boil down the complexities of Gothic architecture to its most essential feature, it would have to be the pointed arch, which was an advancement from the rounded arches used in the early medieval period as well as later.

The pointed arch had several advantages over the rounded arch:

- It shifted the immense weight of the roof to the sides so that the load pushed outward rather than downward;

- This led to the development of decorative flying buttresses on the sides of these cathedrals which strengthened the walls as the weight pushed outward.

- It also allowed the architects to raise the roofs higher than ever before because the weight on the walls was less onerous;

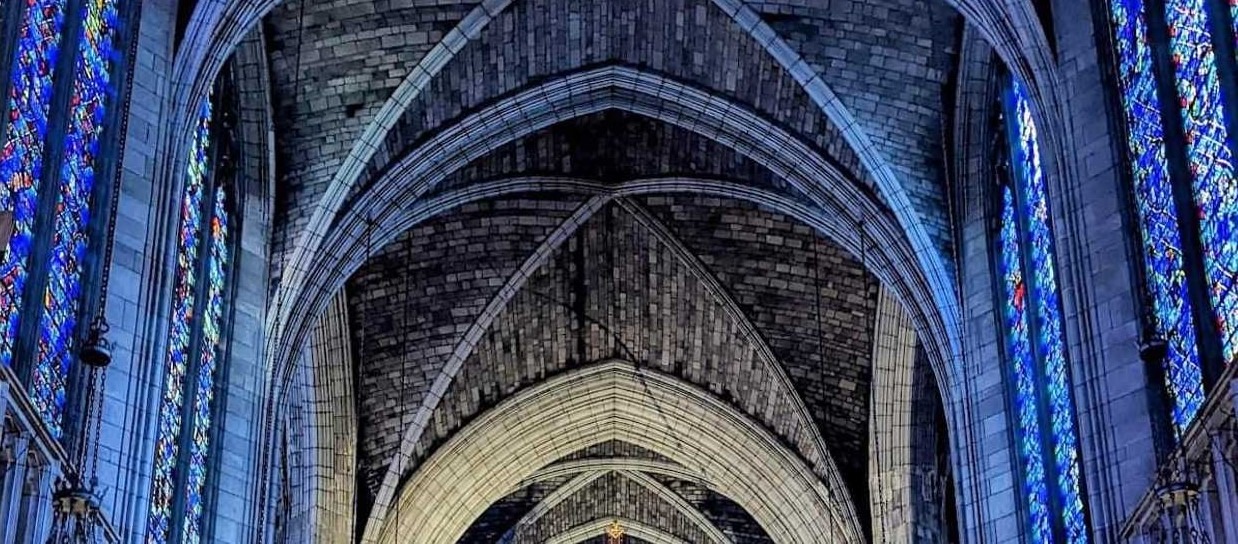

- A further advantage: that the pointed arch allowed the walls to be thinner, which in turn gave them the grand idea of placing big holes in the walls and filling them with stained glass. Wow!

It really is amazing how one simple design change in an arch led to such gracious developments in stone, glass, and form!

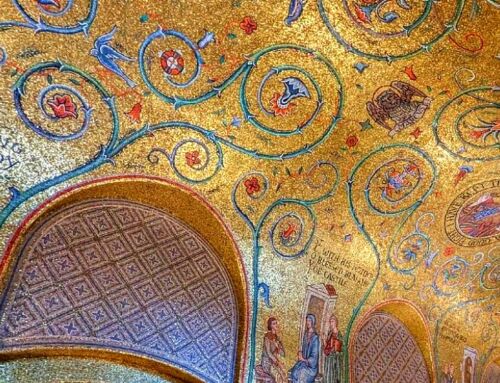

When you look at Romanesque churches, you’ll notice that they don’t have much, if any, stained glass. Their dominant features are mosaics and those huge domes, which sit nicely on the rounded arches.

Grace Builds on Nature

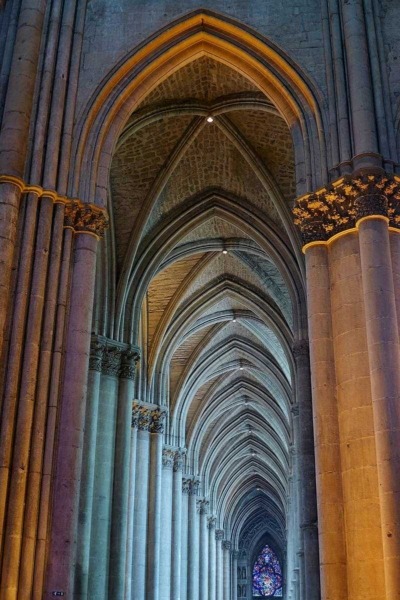

What I like best about the pointed arch is that it almost makes you look up at it once you enter the space. It’s a fascinating and attractive view that mimics something you’ve seen before in nature: a forest.

The succession of pointed arches in a long cathedral corridor creates the impression of trees in a lush forest. The fan vaulting (namely, the stone ribs that hold up the roof) resembles the tree branches as they “fan out” to create a sort of sacred canopy over the viewer’s head. Stunning!

The succession of pointed arches in a long cathedral corridor creates the impression of trees in a lush forest. The fan vaulting (namely, the stone ribs that hold up the roof) resembles the tree branches as they “fan out” to create a sort of sacred canopy over the viewer’s head. Stunning!

If the dome sitting on the rounded arch mimics the “vault of heaven” in a way, the pointed arch reminds the viewer of something natural and majestic, like an oaken forest, that draws the eye up, up, upward—beyond this world, to heaven.

A theological message is integral to this Gothic creation: namely, the beauty of the natural world leads us to the spiritual world, to the world of grace.

As I have always said, many things in this world—natural and human creations—become sacred windows to a higher reality. Nothing displays this better than Gothic architecture.

Oh, and make sure not to miss the aspect of the pointed arch that contains a sort of invisible icon within it: the pointed form can be visualized as a pair of praying hands.

Other Aspects of Gothic

I could offer whole newsletters on all of the other wonderful aspects of Gothic architecture, but I can only list a few in this one, hoping to whet your appetite for learning to “read” these churches more deeply and prayerfully.

Pardon the pun, but the sky’s the limit here! (Links are to previous SW articles.)

- Flying buttresses and stained glass, as mentioned

- Gargoyles and carved statues;

- Elaborate towers and spires

- Clerestory windows (on the second level between floor and ceiling)

- Magnificent rose windows (huge round windows at the ends of aisles)

- Cross-shaped floorplan, and

- Magnificent portals.

Final Note: Gothic Revival

Did you know that there was a revival of Gothic architecture more than seven centuries after the original medieval cathedrals were built? It took that long for architects to get the Renaissance out of their system!

Sacred Heart Basilica at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana

The reason why we see so many Gothic-style churches in American cities is because the 19th and early 20th centuries blossomed into what is known as the Gothic Revival in Europe and North America. The style is sometimes called Neo-Gothic.

These centuries experienced periods of relative stability (between wars, that is), which, combined with economic prosperity and advances in construction technologies, caused the immortal Gothic style to emerge once again to grace the landscapes of so many places.

We could name a hundred US Catholic cathedrals and churches in the Neo-Gothic style, but St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City is probably the most recognizable example of the Gothic Revival in the US (built from 1858-1910).

Many Protestant denominations copied the Catholic style quite effectively with the building of massive churches like St. John the Divine in NYC and the National Cathedral in our own nation’s capital. Both were built in the same general timeframe as St. Patrick’s.

While the Medieval Gothic style was used solely for houses of worship, the Neo-Gothic expanded to encompass a wide variety of buildings, particularly the most exalted and important centers of power in a country.

Case in point: the British Houses of Parliament are pure Gothic Revival (rebuilt between 1840 and 1876 over early medieval foundations).

The Gothic wonder has many facets and many angles, but most importantly, it is a gift that keeps on giving. The myriad Gothic stories written in stone throughout the world have been instructing the faithful to worship for many centuries. Above all, there is one thing their story is not: boring!

Thank you for sharing such a fascinating topic! You have deepened my understanding and thus my appreciation and gratitude for these mysterious and marvelous structures! Some of the photographs you provided are so beautiful, it’s like glimpsing into another world; shadows of Heaven!

Thank you Annabelle! I am grateful that you got so much from the article. Those beautiful structures are really a gift to the world. Blessings!

I went to school at St. John the Divine. They are STILL building it it to this day. Each stone is hand cut and it takes a very long time.