You’ve seen his artwork on countless Christmas cards. His birth name was Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni dei Filipepi (1445-1510 AD) but art history knows him as Sandro Botticelli, or just Botticelli (a nickname which means “little barrel”!)

Alessandro took the surname of his father (Mariano), which may give us a clue as to the subject of our newsletter today. He was Marian to the core.

Botticelli’s self-portrait.

I hope (and presume) that Botticelli made it to heaven, and someday, if I make it to heaven, I’d like to sit down with that amazing Renaissance artist and ask him why he painted more than two dozen pictures of the same subject in the course of his career – his beloved Madonnas! Each one is a masterpiece in its own right.

The “Madonna” is a particular genre of art which depicts the Virgin Mother holding the Child Jesus, whether as an infant in her arms or at her feet as a young child. It may also include other figures, but Mary and Jesus are always at the center.

And although it’s not an exclusively Italian genre, no one does Madonnas better than the Italians! (The very word Madonna means “my lady” in Italian.)

Primary Subject Matter

But Madonnas were just one of the ways Botticelli presented the Blessed Virgin to us. If you add his other Marian themes (such as several Annunciation scenes, the Adoration of the Magi, the Pietà, etc.) it is clear that Our Lady is the primary subject matter of his life’s work.

I counted over four dozen Marian images on Wikipedia’s list of Botticelli paintings. Wow!

His paintings reveal an artist who seemed to be on regular speaking terms with the Blessed Mother. Only that level of familiarity with a subject could lead to such vast and versatile artistic expression, I believe.

His paintings reveal an artist who seemed to be on regular speaking terms with the Blessed Mother. Only that level of familiarity with a subject could lead to such vast and versatile artistic expression, I believe.

In Botticelli’s collection, Our Lady is both physically and spiritually beautiful, always inviting us to focus on the Christ Child before her, and exquisitely delicate in all her features. She is always arrayed in the finest attire of earth and heaven.

Having said all that…there is also one very natural reason why Botticelli could paint such ravishingly beautiful Madonnas.

He had his own Renaissance supermodel whose looks could not have been more perfectly suited to modeling his delicate Madonnas (and, um, a couple of Roman goddesses too, as we will see.)

La Bella Simonetta

I’m not an art history expert by any means, but I have eyes, and my eyes tell me that one particular face crops up in a great number of Botticelli’s paintings as well as on many of his beautiful Madonnas.

It was the face of Simonetta Vespucci, whom everyone in Renaissance Florence called “La Bella Simonetta” (Bella means, simply, beautiful.)

Pictures are worth a thousand words, they say, so I trust your eyes too will discern the remarkable similarities of the faces in a range of Botticelli’s paintings.

Although scholarly opinion may differ on some of them, the consensus of both experts and amateurs is that they are all depictions of this one ravishing Renaissance beauty queen. (Note the nearly identical chin, eyes, nose, hair color/style in all of these images, despite some minor differences.)

Simonetta was celebrated as the most beautiful woman in the Republic of Florence at the time, which was probably an extraordinary feat in itself and eminently true, given how everyone seemed to adore the very ground she walked on.

As the daughter of a Genovese nobleman, she was married within her caste to a Florentine nobleman named Marco Vespucci sometime in the late 1460s. Her family was closely connected to the ruling Medici family in Florence, which is how she came to be associated with the art of the High Renaissance.

And does the name Vespucci sound familiar? It should. Her husband was a cousin to the famous explorer, Americo Vespucci, whose first name now graces a whole hemisphere of the New World.

The Goddesses

Another artistic focus of Botticelli (at least during the middle period of his career) was Roman mythology, and from this subject matter came his two most famous works, The Birth of Venus and Primavera (Springtime). They are immortal classics.

Who is not familiar with the exquisitely delicate and ravishing faces of his mythological women? Even if you can’t name the artist, you know the beauties. It’s almost as if they come alive when you look at them.

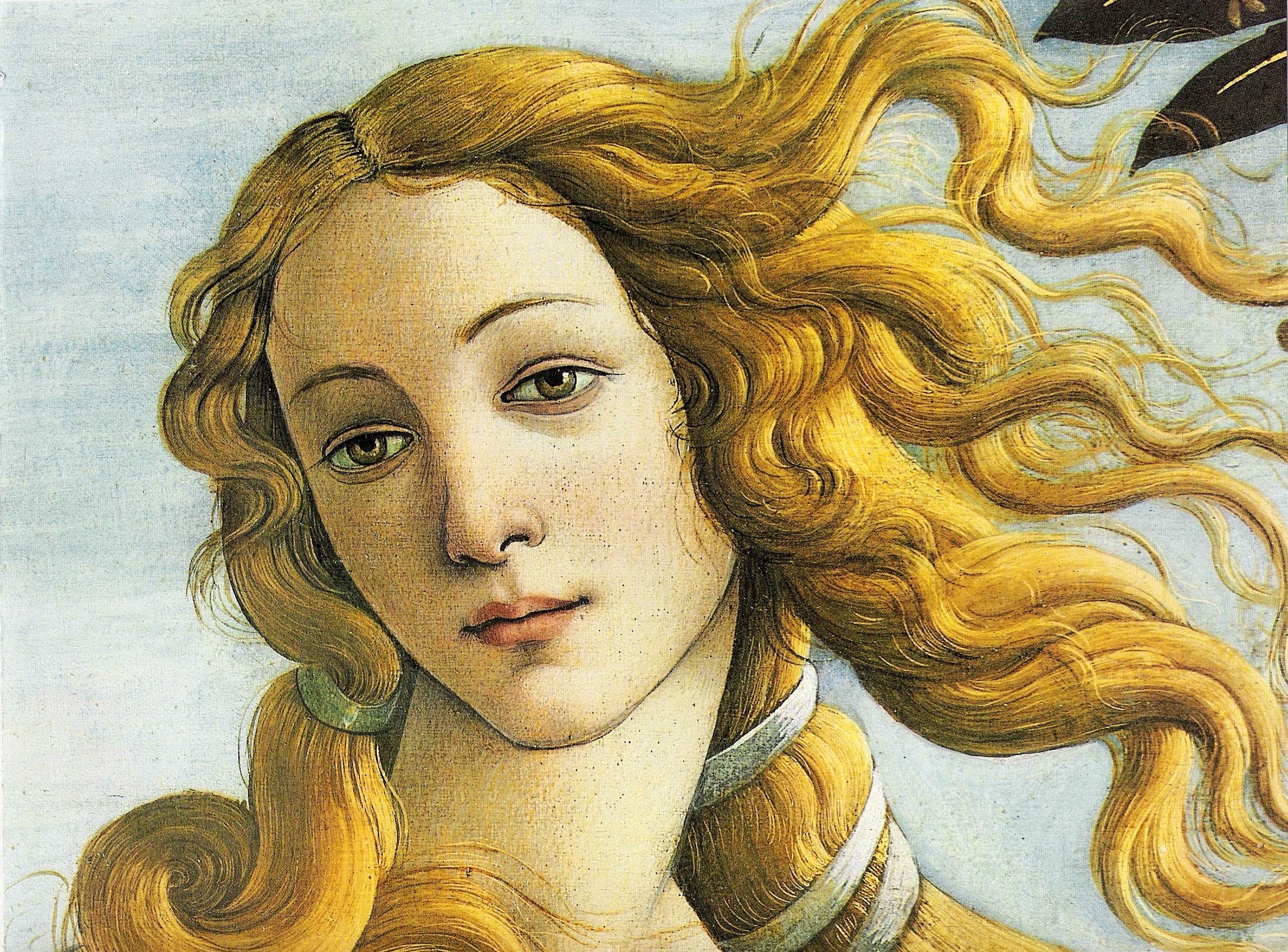

Here we find the portrayal of La Bella Simonetta’s radiant beauty in full form:

Detail from The Birth of Venus

Detail from Primavera (Springtime)

I told you she was a supermodel. (And trust me, there are many more images of her that we could show.)

Yet, the ethereal beauty of Boticelli’s goddesses cannot rival the total and perfect beauty of his Madonnas because goddesses don’t actually exist, and even supermodels diminish in beauty as age and time take their toll.

On that point, Simonetta, sadly, died at the tender age of 22, in the prime of her physical beauty and popularity. It is believed that she died of tuberculosis. Sic transit gloria mundi! (“Thus passes the glory of this world.”)

But how blessed we are that Botticelli spent those few years of her earthly sojourn in Florence (and, apparently, many years following her death) immortalizing La Bella Simonetta as the ideal of feminine beauty.

Yet, as a man of deep faith, Botticelli knew that another beauty queen, in a very literal sense, stands in an entirely different category, transcending all earthly beauty, and he found her in the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Madonna-Like Beauty

If Simonetta was the model for his Madonnas, she was a fitting one. One might ask if Our Lady was as physically beautiful as La Bella, and of that I have no doubt. But we are not given to know this for a fact until we meet the Mother of Christ face to face.

If Simonetta was the model for his Madonnas, she was a fitting one. One might ask if Our Lady was as physically beautiful as La Bella, and of that I have no doubt. But we are not given to know this for a fact until we meet the Mother of Christ face to face.

In any case, all the seers who have received apparitions of Our Lady say that she is indescribably beautiful. They usually stop short of even trying to recount their experiences of her beauty.

What we do know is that Botticelli’s Madonnas come alive the same way his more secular depictions of Simonetta seem to. Or maybe it’s better to say that his Madonnas seem to draw us into their beauty, an effect that few other artists are capable of achieving so perfectly.

Given the extraordinary amount of Marian imagery in Botticelli’s life’s work, we can only whet your appetite for further viewing by highlighting three of his matchless Madonnas.

Here are a few facts to know before you view these images in greater detail:

- These three were painted in the round, a form of presentation called the “tondo” in Italian (short for “rotondo”).

- They are huge, as paintings go! Each measures more than four feet in diameter, augmented by elaborate golden frames.

- Each is painted on a wood panel (more durable than canvas, thankfully), and

- Boticelli used tempera (egg-based), not oil paint, for these works. Oil eventually supplanted tempera as the artistic standard right at the time Botticelli’s career came to an end, ca. 1500. Leonardo’s Mona Lisa (ca. 1505), for example, was the full expression of the new era of oil painting.

I’ve offered only a few comments about the images below to help focus your attention on their deeper aspects, but I can’t pretend to add anything of significance to a Botticelli Madonna.

Their beauty speaks for itself! Enjoy the views.

Madonna of the Magnificat (1481)

You’ll easily notice the five angels who hover around Our Lady, two of whom hold what looks to be a semi-transparent crown above her head.

The wavy hair and curls, the colorful Renaissance garments, and the transparent veils and sashes – all are pure Botticelli!

Note also that Our Lady is dressed in the traditional colors of the Madonna, red tunic and blue mantle, symbolizing heaven and earth.

The distinctive aspect of this Madonna is that Mary seems to be writing the Magnificat (her own canticle in the Gospel of Luke). Botticelli thus presents Mary, not as a passive recipient of God’s graces, but as an active participant in the mystery of the Word made flesh.

One final detail: Jesus’s tiny right hand touches the Magnificat written on the right-hand page of the book – as if blessing it.

Madonna of the Pomegranate (1487)

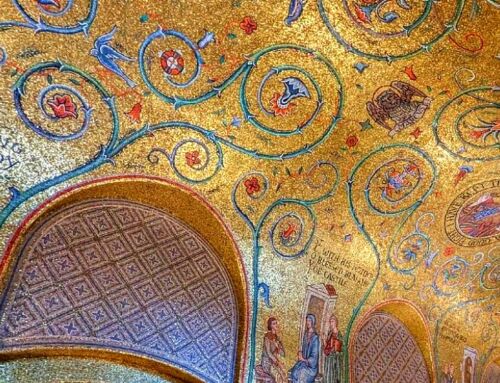

If the only elements of this extraordinary painting were the six angels with their facial expressions, symbols, and raiment, it would be a Renaissance masterpiece all its own!

But the angels also fulfill a distinct artistic function: they “frame” the Virgin and Child perfectly (three on either side) under a sun of glorious rays that descend from heaven to give this Madonna, very literally, a supernatural feel.

But the angels also fulfill a distinct artistic function: they “frame” the Virgin and Child perfectly (three on either side) under a sun of glorious rays that descend from heaven to give this Madonna, very literally, a supernatural feel.

Mary stares out, almost mournfully, at the sea of sinful humanity that longs for the redemption that only her Child can provide.

The Baby Jesus looks at the viewer directly with intelligent, piercing gray eyes. His lovely little left hand touches a pomegranate that looks curiously like a human heart in size, shape, and color. His right hand is raised in blessing.

Madonna and Child with Eight Angels (1478)

The model for this exquisitely beautiful Madonna must clearly have been the same ideal woman who modeled Botticelli’s mythological Venus. Yet, the Roman goddess does not presume to have the diaphanous halo whose faint outline we can discern around Our Lady’s head.

Under it, the sinuous veils (one decorative blue, the other translucent) cover up what might be Venus’ curls, but the eight angels surrounding her have no such hair restrictions. They all have distinctly ebullient curls! Yet, they also silently proclaim their modesty in the lilies above their heads, symbolizing angelic purity.

The number eight is understood in symbolic terms as a sign of the Resurrection, which took place “on the eighth day.” As before, these angels “frame” the Mother and Child. Four of them (at right) seem to be singing from a book while the other four wait in attendance on their Queen.

The Virgin once again looks out at the mass of humanity in need of redemption, but the Christ Child turns His radiant visage to the viewer in a call to be attentive to the Mystery whom the Virgin Mother cradles in her arms.

Well, unfortunately, we must stop here, but I hope you can now more deeply appreciate the meaning of the images we see on Botticelli Christmas cards every year.

If you were to adopt just one Renaissance artist as a guide to Marian spirituality, you could never go wrong with Alessandro (di Mariano) Botticelli. As the title of this article says, his Madonnas simply take your breath away.

Soul Work

How deeply the Catholic Tradition venerates Our Lady! Earthly beauty is certainly a marvel to behold, but Mary’s beauty is total: body, soul, and spirit.

The bridegroom in the Song of Songs (4:7) describes his lover in these terms: “you are all beautiful” (Latin: tota pulchra es). So, it’s not hard to see why that phrase has unanimously been applied to the Virgin Mary throughout Christian history.

Some Christians do not come from a tradition that venerates the Blessed Virgin, so it might be hard to place her in a spiritual category all her own, but I would encourage them to remember the scripture passage, Luke 1:48, where Mary proclaims that “all generations will call [her] blessed.” It is a statement of fact, not a boast.

No Christian worships Mary. She is not God or a goddess. She is “blessed among women” (Luke 1:42), which is where the Church derives its deep sentiments of Marian veneration.

For these Christians and for those who already venerate Our Lady, perhaps a few moments of meditation on these iconic images from Botticelli will help to teach something that really can only be experienced in personal contact and prayer: total beauty.

—–

Photo Credits: The source for all Botticelli images is Wikimedia Commons; all images are in the public domain.

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 8/6/23. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Beautiful