Back in 1987, the clever creator of the Far Side comic strip, Gary Larson, drew a single-panel cartoon entitled simply, “Michelangelo’s father.” It shows a toothless old man standing at the foot of a very tall ladder, looking up, and apparently giving instructions to his son during the painting of the Sistine Chapel.

What makes it so funny is that the viewer gets to hear only the father’s side of the conversation:

Watch those flesh tones, son – they’re too yellow … How much they payin’ you for this? Back in my day we’d finish a ceiling twice this big in less than a week! ‘Course in those days we had to make our own brushes.

Hilarious! And in case you were wondering, it wasn’t Michelangelo’s father who taught him to paint and sculpt. His father was actually a banker who was not very pleased that his only son decided to run off to art school.

Genius Proportions

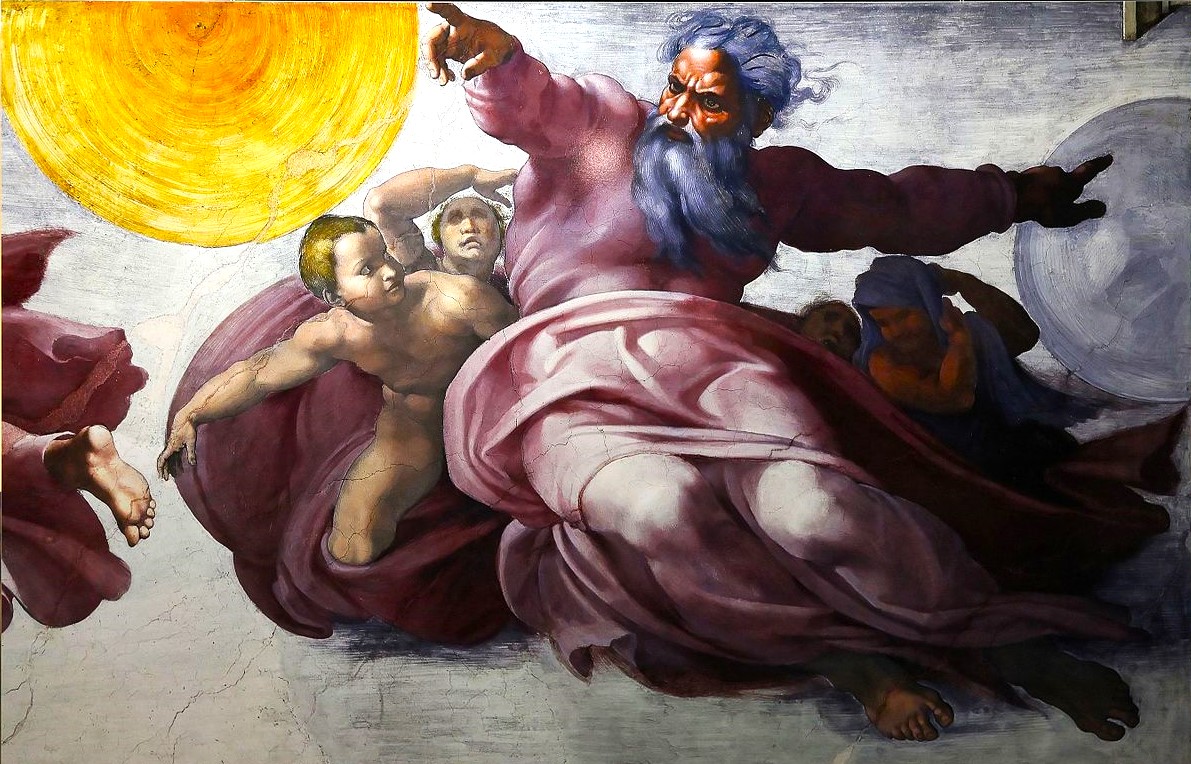

But the rest of the world is glad he did. Art was both his son’s passion and his calling, and eventually that son became the world’s undisputed grandmaster of sculpture, not to mention the fiery, temperamental, and often brash fresco painter of the Sistine Chapel.

And did you know that Michelangelo also designed the magnificent dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome?

Sculpture, Painting, Architecture. He did it all, and he did it supremely well, even for an era that was filled with geniuses in those fields.

Michelangelo Buonarotti lived to nearly 89 years of age (1475-1564) and offered his gifts to the world for nearly eight decades with an amazing generosity of spirit. It is said that in his 18 years of work on the Dome of St. Peter’s he never accepted a cent from the pope who commissioned him. He did all for the glory of God alone.

That’s not necessarily a pitch for his canonization. Michelangelo surely was a man of faith, but, despite his name, he was hardly an angel!

The Infamous Portrait

To give you an idea of what I mean, when he was painting the Final Judgment scene on the back wall of the Sistine Chapel (from 1536 to 1541), Michelangelo painted the face of one of his enemies onto an ugly, donkey-eared figure enveloped by a snake. He placed this mythical creature in the very bottom corner of the mammoth painting (so that observers could see it more easily.)

Said enemy was actually the pope’s Master of Ceremonies, and when Archbishop Baigio da Cesena found out about this insult to his dignity, he complained bitterly to Pope Paul III about the uppity artist. But the pope is alleged to have replied,

“Well, if he had put you in Purgatory I might be able to do something about it….”

It seems that Michelangelo had placed the good prelate in Hell. Done deal.

Mentors or Influencers?

There is some debate as to whether a world class genius in any field can actually be taught the elements of his particular realm of genius or whether he has them innately. I maintain that both are true, and Michelangelo is a prime example.

Here we have to make a distinction between those who teach (in the sense of apprenticeship) and those who exercise influence (in the sense of opening up avenues for that person’s genius to express itself).

Here we have to make a distinction between those who teach (in the sense of apprenticeship) and those who exercise influence (in the sense of opening up avenues for that person’s genius to express itself).

The question has a direct answer in Michelangelo’s two mentors. As an early teen, he was apprenticed to a master painter in his own right who became one of the more famous Renaissance painters. Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448-1494, inset picture), who was himself a student of the famous Donatello (1386-1466). This was quite an artistic pedigree.

But Ghirlandaio is the very reason Michelangelo had the ability to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling so many years later. He had been taught to paint frescoes by a master of that technique.

In his later teens, his sculptural mentor was more of an influencer than a teacher – at least Michelangelo thought so. The man was a Florentine sculptor named Bertoldo di Giovanni (1420-1491), who was the master in residence and caretaker of the Medici family’s art academy. He is almost entirely unknown today due to his being eclipsed in reputation and talent by his most famous student.

In terms of influence, however, Bertoldo held a key that opened a door for the young artist. He was the one who recommended his prize student to Lorenzo di Medici for further opportunities at artistic development. This recommendation exposed Michelangelo to a vast range of other artistic prodigies and launched the young sculptor into his prime work of sculpting for rich patrons.

The first and grandest of all his masterpieces followed soon after: namely, his famous Pietà, which he sculpted at just 24 years of age.

Taught or Caught?

Michelangelo always claimed that no one could have taught him his trade, and it’s not hard to see that he had a point. When you observe the incomparable grandeur of the Pietà or his David, for example, how is it possible that one could be taught to sculpt works like these?

Rather, he “caught” or picked up the elements of sculpting from his influencers and environment, but he did not get his talent or techniques from them. So he claimed.

There is another little-known story of Michelangelo’s life that showed a certain artistic influence on him as a child. His mother died when he was just six years old, and he was then given over to the care of a nanny in those tender years. The nanny’s husband was a stone mason. The artist’s love-affair with stone writes itself after that.

As for architecture: if you can believe it, the creator of the dome of St. Peter was entirely self-taught. Imagine. Further wonder: he only began to study architecture at the age of 40. He was 71 years old when the pope commissioned him to do something no one had ever done before: raise a dome the size of Rome’s ancient Pantheon 200 feet off the ground and place it on the top of the still unfinished St. Peter’s!

Genius vs Talent

The famous French philosopher, Etienne Gilson, says that genius differs from mere talent in one major respect: genius absorbs and assimilates the best examples of one’s field of expertise and then produces unique creations in that field out of whole cloth.

Talent, on the other hand, is something less than genius. It may express itself in precocious and fascinating ways, but talent is essentially imitative. It reproduces the designs that have gone before it and adapts what it sees to its own style.

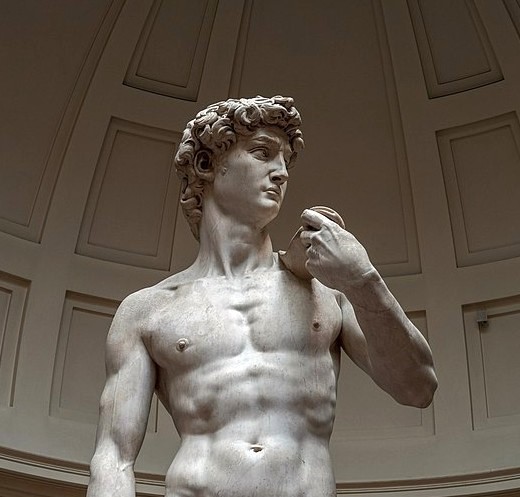

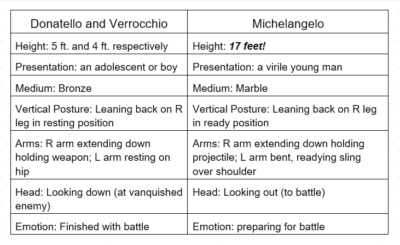

One brief example using Michelangelo’s David (completed in 1504) should make this clear. His genius was not in being the first to sculpt a freestanding David statue. That title belongs to Donatello who crafted a very bizarre bronze sculpture of David in the 1440s, sixty years before Michelangelo carved his marble monolith.

Then, another famous Florentine sculptor, Andrea del Verrocchio, fashioned another (slightly less-weird) bronze David in the year Michelangelo was born (1475). Verrocchio was Leonardo Da Vinci’s mentor, and it is sometimes claimed that Leonardo was his model for the statue.

Be that as it may, both bronze images of David show the young biblical patriarch standing over the severed head of Goliath holding the sword used for decapitation. In other words, they picture a victorious David after battle.

Surpassing His Tradition

Having studied these sculptures, which were in the Medici collection at the time, Michelangelo came up with a different – rather genius – idea when received a commission to carve a David out of a huge, abandoned chunk of marble for the community of Florence.

His idea was to show David before battle, not with Goliath’s sword but with the actual lethal weapon he used to slay the giant: the slingshot.

The intrepid youth looks with steely eyes at his nemesis and contemplates his battle strategy. I’m sure you’ll be able to notice the superiority of Michelangelo’s genius in these comparison pictures:

Donatello

Verrocchio

Michelangelo

You may also notice that Michelangelo took certain aspects of past masters – particularly, the similar posture – and enhanced their previous, rather bland, styles with his own genius. This checklist offers a few points of comparison:

As Gilson noted above, genius is not a detachment from a tradition; even less is it a rejection of past precedents. Rather, it’s a mature artistic mind that absorbs, assimilates, and re-presents the imagery in stunning new formulations. Michelangelo has clearly done this with his David.

There is literally no comparison between his style and his forebears in craftsmanship, fineness of musculature, intimate detail, or even emotion elicited by the gigantic marble masterpiece. They were masters in their own right. Michelangelo was a genius.

A Sacred Window

Is human genius a sort of sacred window into God’s creative blessing on the world? I have no doubt the answer is affirmative.

As noted, the possession of pure genius doesn’t assure that a genius is easy to live with (Beethoven’s atrocious personal care and egotism is one obvious example). Long human experience attests that most geniuses are proud of their talent and tend to lord it over others, and sometimes the results are not as pleasant as their works. Apparently, neither Michelangelo nor Leonardo ever gave a single shred of credit to their mentors.

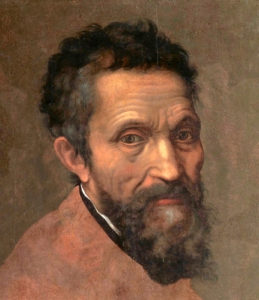

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

Church history also witnesses a number of authentic geniuses in their respective fields who have become canonized saints (St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Augustine in theology, for example), but let’s face it: holy geniuses are exceedingly rare!

In the final analysis, our lives are richer because of the many geniuses who have gone before us and offered their unique gifts for the sake of others, but we can be thankful that we don’t have to live with them.

So, whenever we find ourselves reacting to some astonishing work of genius in amazement or wonder, we are usually looking through a window that shines a faint light of truth, beauty, or goodness on our lives from beyond.

As prodigious as the work of genius may be, it’s still only human. It’s just a spark of the grand bonfire of divine creativity…from the One who created genius itself.

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 4/30/23, so it does not end with the regular Soul Work section. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Photo Credits: David (Verrocchio), (Donatello), (Michelangelo); Pietà; the following via Wikimedia Commons: Dome Interior Erik Drost, CC BY 2.0; Dome Exterior, Dennis Jarvis; Sistine Chapel Ceiling, Aaron Logan; Ceiling (Brass Serpent Detail); Ceiling (Oracle of Delphi Detail); Ceiling (Frank Vincentz Creation of Sun and Moon Detail); Biago da Cesena; Portrait of Michelangelo, attributed to Daniele da Volterra, Public domain, c. 1545. Self-portrait of Ghirlandaio.

Leave A Comment