A more beautiful form of music does not exist.

Some have described it as a flowing river of sound, but Gregorian Chant feels more like a gentle, insistent wind beneath the wings of a majestic eagle carrying him higher and higher into the heavens.

It has that same effect on the human soul too. It raises the mind and heart upward like a wind of spirit.

An Organic Creation

No one knows the actual origins of Gregorian Chant because no single person or place developed it. It grew organically out of the celebration of the sacred liturgy and the innate desire of the human heart to sing the praises of God with the human voice. This was nothing new to our tradition: the psalms of the Old Testament were performed to music and used in the worship of Yahweh in the Jerusalem Temple.

Yet, Hebrew chant was not unique either. Chanting as a form of sacred music is reflected in all ancient cultures, many of which are extremely beautiful and some of which are still in use in various forms to this day. (Such as this amazing ancient chant of the Lord’s Prayer in Jesus’ own native tongue.)

For Liturgical Use

Gregorian Chant has been the standard musical language of the Latin Church since the late 700s AD, although it is much older than that in origin. It received its name from Pope Gregory the Great who reigned as pope a century and a half earlier (590-604 AD), but Gregory didn’t directly create this form of music, so it’s a bit unusual that this style of music bears his name.

The essential reason is that Pope Gregory was a reforming pope and a church builder who standardized the Latin liturgy and is known to have loved and promoted sacred music. It is believed that he compiled a book of chants for liturgical use (called an antiphonary) based on an earlier form of Roman chant, though not the exact form of Gregorian Chant that has come down to us.

Gregory’s old Roman chant fused with French (Gallican) chant traditions around 750 AD, and then Charlemagne ordered it to be the standard liturgical music for worship in his empire. From there it spread through the entire Church by way of the influence of Benedictine monks, particularly during the 9th and 10th centuries. The monks came to refer to it as “Gregorian” as a homage to the founder of the musical tradition, much the way an important city like Washington DC is named after a historical figure of great importance who didn’t actually build the city!

Evangelization and Prayer

We shouldn’t overlook the evangelization aspect of this form of music either.

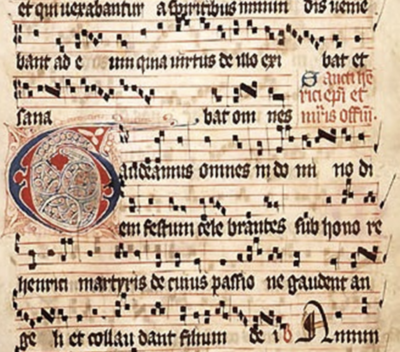

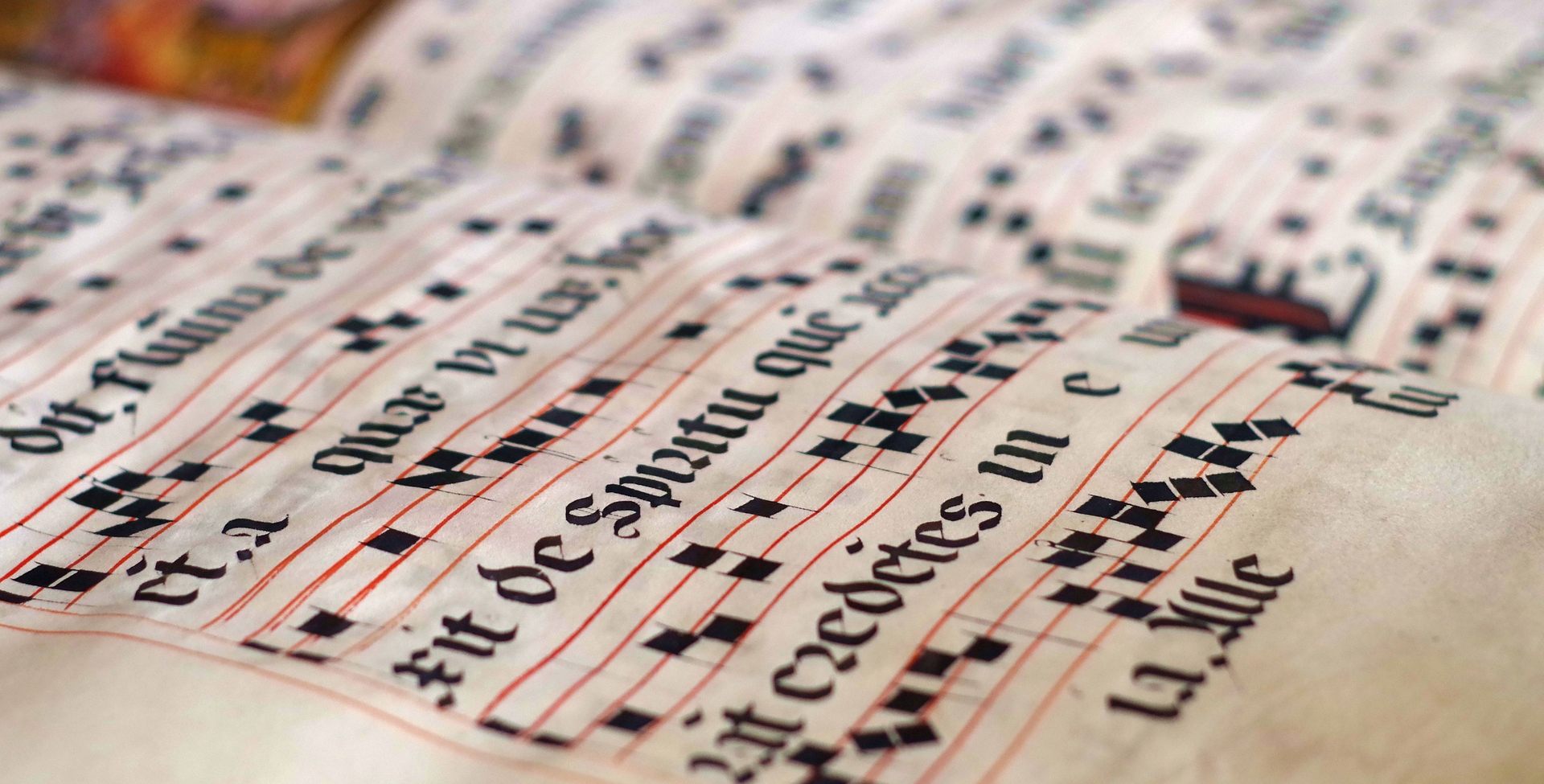

Before Gregorian Chant was written down, all chants were memorized and passed on in oral tradition. Around the time of Pope Gregory, however, notations began to be added between the lines of the Latin texts which directed the flow and direction of the music. These notations looked more like shorthand squiggles than musical notes. During Charlemagne’s time, however, the monks began to write down the notes so that the music could be used to evangelize other lands and people who were not familiar with the Roman musical tradition.

Before Gregorian Chant was written down, all chants were memorized and passed on in oral tradition. Around the time of Pope Gregory, however, notations began to be added between the lines of the Latin texts which directed the flow and direction of the music. These notations looked more like shorthand squiggles than musical notes. During Charlemagne’s time, however, the monks began to write down the notes so that the music could be used to evangelize other lands and people who were not familiar with the Roman musical tradition.

Above all, Gregorian Chant is prayer. It owes its sublime beauty not only to the richness and simplicity of its tones but also to its very soul: every word behind Gregorian chant is prayer, the prayer of the worship of God in the Roman Catholic Latin liturgy. There is no such thing as secular Gregorian Chant. It is a form of music entirely dedicated to God’s glory.

Dr. Peter Kwasniewski has said that “the chants are the clothing that the liturgical texts are dressed in.” A fine observation.

A Few Facts

Since I am not in any way an expert on the techniques or mechanics of Gregorian Chant (here are three excellent resources if you are so interested), I only wish to point out a few characteristics of Chant that the intelligent lay person should look for in this form of music:

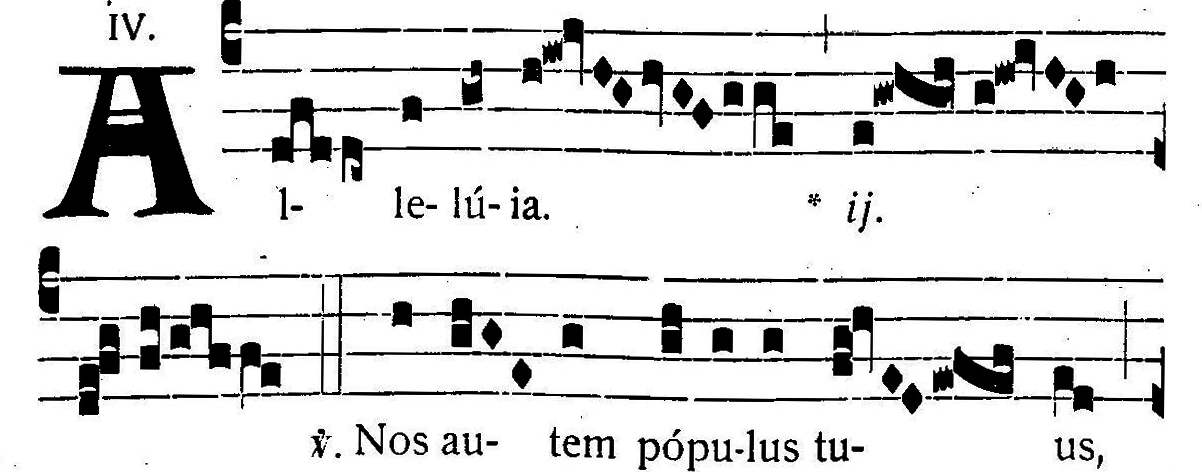

- Its notes are square rather than round notes like we use today; these little squares were created by single strokes of the flat calligraphy pens that the monks used to copy the chant in medieval times, and the square notation remains the standard way to denote chant to this day;

- In addition to the square notes, the dots, flag staffs, slides, and vertical lines that appear in chant notation all have their own meanings (such as pauses, up/down voice modulations, glissandos, etc.), and the chanter has to know them in order to sing the music correctly;

- Gregorian chant is monochromatic (namely, a single tune sung by all voices together) so it is written on a simpler four-line musical staff rather than the standard five-line register which is used for music today; polychromatic music (i.e., many voices singing different parts) generally has a wider range and needs more lines!

The Alleluia chant you will hear in the video below defines the word “sublime.” You will probably feel, as I did, that upward motion of your spirit when you listen to even a few of the opening bars of this magnificent chant.

He is Risen – Alleluia!

Gregorian Chant in a Benedictine Seminary (duration, 3:37)

Soul Work

Is there anything in your life – any object, place, time, or habit – that is exclusively dedicated to God, something that has no other use or purpose but worship?

Each of our lives should contain these elements of the sacred in very tangible forms. Despite the hard press of our day-to-day living, we should even expand and multiply them to meet the deeper needs of our souls. Sacred places and things that belong only to God are necessary for spiritual growth.

For example, the effort required to carve out a sacrosanct prayer time in the course of our busy day always pays us back abundantly in greater focus and energy that comes from spending one-on-one time with Christ. All the better if we have a sacred space to go to (such as an adoration chapel) or even a place in our own homes that we reserve for prayer.

This is a way of applying the lesson of Gregorian Chant. It’s an experience of sublime beauty like no other because it is dedicated exclusively to the Source of all Beauty.

Leave A Comment