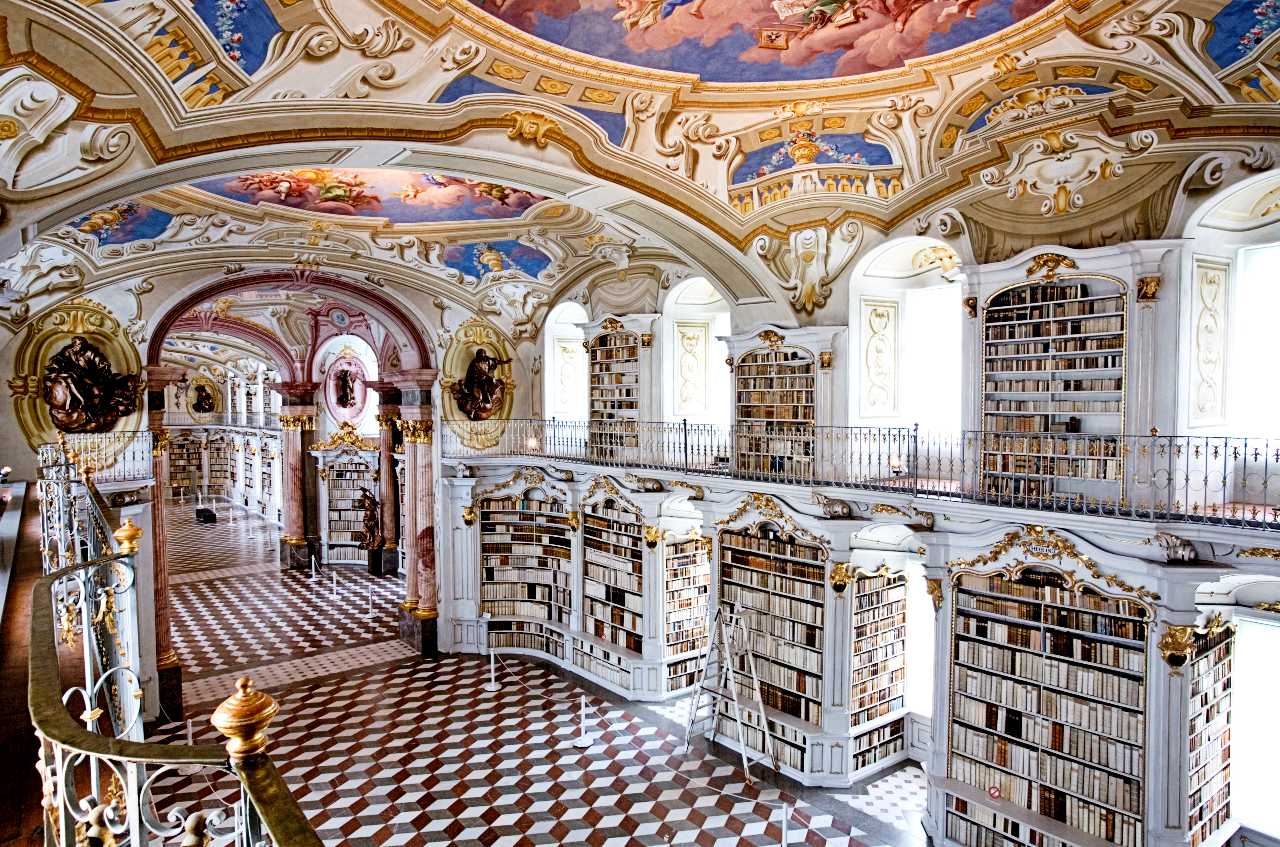

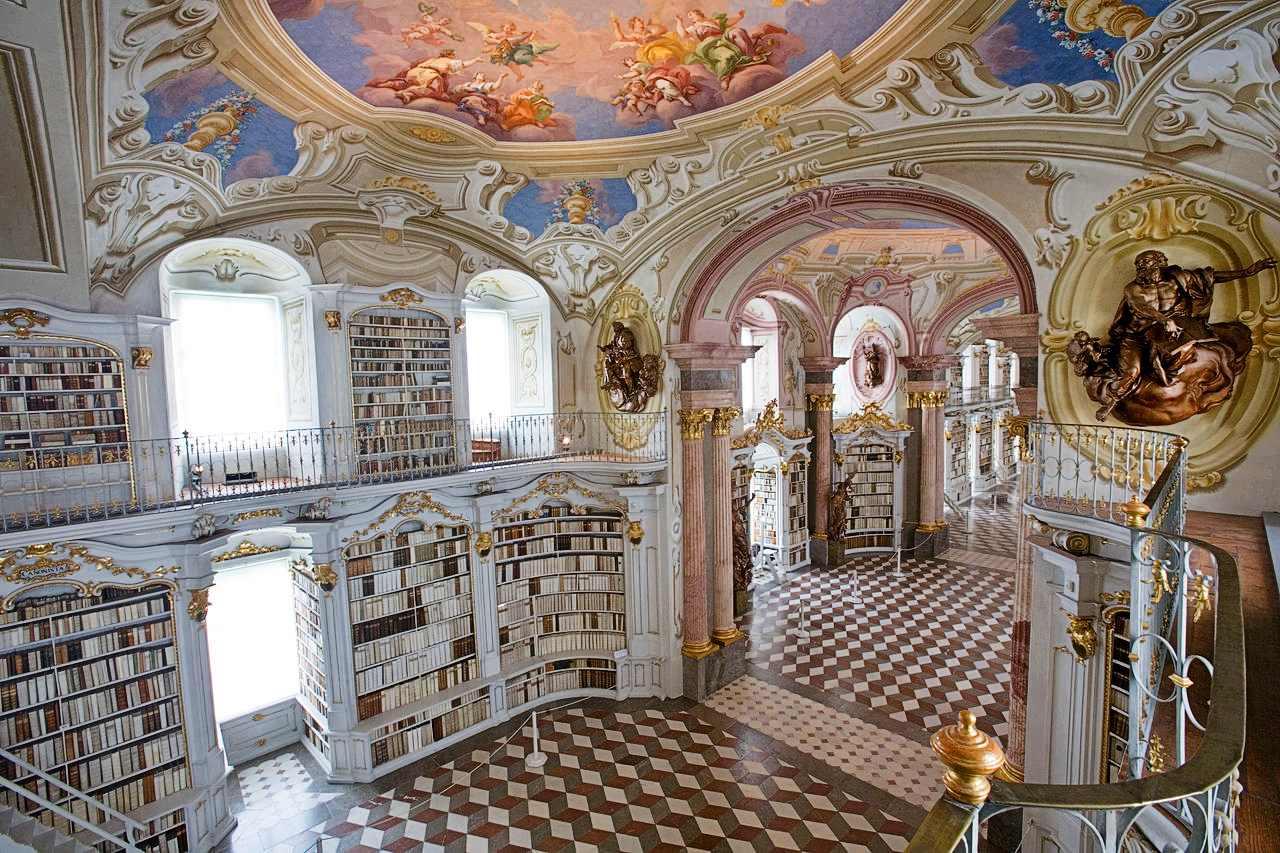

If it is not the most beautiful library in the world, it certainly ranks in the top tier. The library of the Benedictine Abbey of Admont (Austria) is so breathtakingly beautiful that I wonder how any student or scholar could ever get anything done in those surroundings!

The Abbey itself was founded in 1074 AD by the Archbishop of Salzburg who wanted to Christianize the center region of Austria which had scarcely been touched by the Church’s evangelization efforts up to that point. So he wisely sent the Benedictines who built a monastery, established parishes, preached to the local people, and began to educate them about the faith.

The Abbey itself was founded in 1074 AD by the Archbishop of Salzburg who wanted to Christianize the center region of Austria which had scarcely been touched by the Church’s evangelization efforts up to that point. So he wisely sent the Benedictines who built a monastery, established parishes, preached to the local people, and began to educate them about the faith.

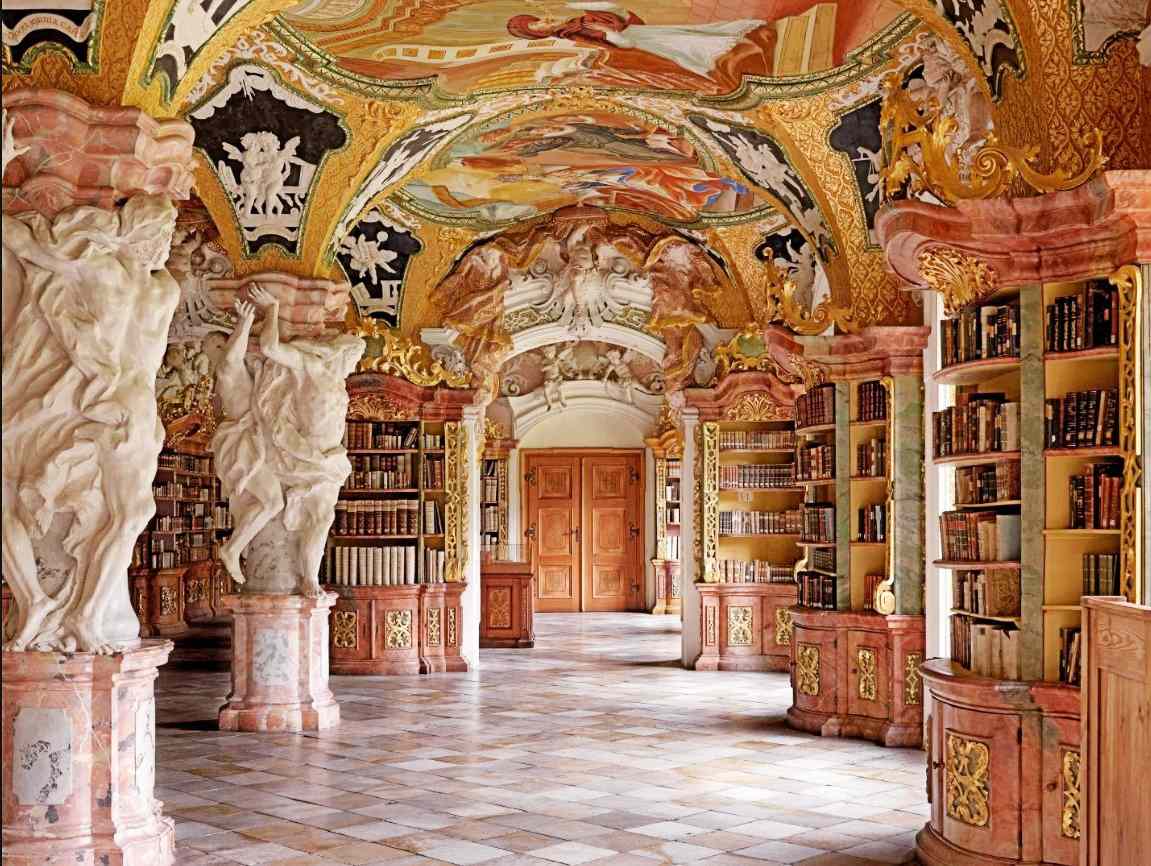

The library of our story wasn’t to be built for a full seven centuries after the founding (it was completed in 1776), but the monks began collecting books and ancient manuscripts from the start to make their new monastery a place of learning and culture. The Abbey’s masterpiece library is a jewel of late Baroque art and architecture.

Admont Library is not unique in the world of monasticism, however. It is one of the many amazing accomplishments of the Benedictines throughout history. It stands within a whole tradition of learning and culture that dates back to the founder of Western monasticism himself.

A Light in the Darkness

The birth of St. Benedict of Nursia (480-547 AD) coincides almost exactly with the fall of the Roman Empire. The latter is generally dated to 476 AD. The end of Rome was the beginning of what we commonly call the Dark Ages, and St. Benedict was to be the brightest light in that darkness.

As a young man, Benedict traveled to Rome and witnessed firsthand the decadence and chaos that took over society when the Empire’s organizing structure fell apart. The old society was being tossed about on barbarian waves like a ship without a rudder. Benedict realized there was no way for him to remedy the chaos, so he withdrew from the world and lived in a cave on Mount Subiaco near Rome for three years asking the Lord to show him what he must do with this life.

And the Lord answered – in a striking way.

Seeing Benedict’s holiness and radical way of living, many men were inspired by his example and wanted to join him, so he gathered around him a community of like-minded men who prayed, worked the fields, and fled the corruption of the world. For this community – and 12 others he founded – Benedict wrote his famous Rule (founding document) for a new form of religious life that became the basis of all of Western monasticism after that.

Fr. William Slattery beautifully expresses the powerful force that grew out of this new experiment in radical Gospel living:

Down that mountainside came a trickling stream of Christian life that, with the centuries, began to grow and swell until it became a mighty river of grace and culture irrigating the plains and valleys of Europe. Benedict and his monks can rightly be called “Fathers of European Civilization”, for during the Dark Ages their monasteries became “the storehouse of the past and the birthplace of the future” (Heroism and Genius, 59).

With uncanny insight and zeal, the earliest generations of Benedictine monks saved a good deal of the classical manuscripts from Rome and Greece that would have been lost in the barbarian invasions were it not for the monasteries. In doing that, they literally enabled Western civilization to grow out of the ashes of the Roman Empire. The political and social structure died, but the best of the culture was preserved in the monasteries, which is the reason we can read the writings of Plato, Aristotle, Homer, Tacitus, Marcus Aurelius, and Cicero today.

The order’s mission of evangelization through a fusion of prayer, work, learning, and culture is the reason why libraries have always been attached to Benedictine monasteries. You might not know it because they are unobtrusive, but Benedictine monastic libraries are everywhere, especially throughout Europe. For example, an exhaustive study of the Medieval Benedictine libraries in England alone fills four volumes of nine hundred pages each!

It is an awesome spiritual legacy.

Libraries and Learning

In practical terms, you can’t preserve human civilization unless you preserve concrete sources of it like art, music, architecture, books, and critical documents. You also can’t preserve religious culture unless you promote forms of religious genius that we see in monastic creations like Gothic architecture (the prototype of the Gothic church is the Benedictine monastery of St. Denis outside Paris) and religious music and art (such as Gregorian Chant and the Book of Kells, among other gifts.)

Baroque art, architecture, and music are known for their florid expressions and grandiose designs such as the Versailles Palace in France and St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, built during the same era. Bach and Handel are Baroque composers and Caravaggio and Rubens are Baroque painters, just to offer a concrete idea of what the styles were like.

But the Admont Library is a unique work of grace in that it is not just the creation of one discipline; it is a fusion of art, architecture, learning, prayer, and evangelization – essentially the Benedictine ideal – all wrapped up into one gorgeous institution. It is so beautiful that one author called it a “real-life fairy tale library”!

As you view the images of the library, here are several things to note about it:

- First and foremost, Admont is the largest monastic library in the world holding some 200,000 books (only 70,000 of which are displayed in the publicly

accessible areas);

accessible areas); - The library’s collection contains about 1500 medieval manuscripts as well as over 500 handwritten texts produced before the year 1000 AD;

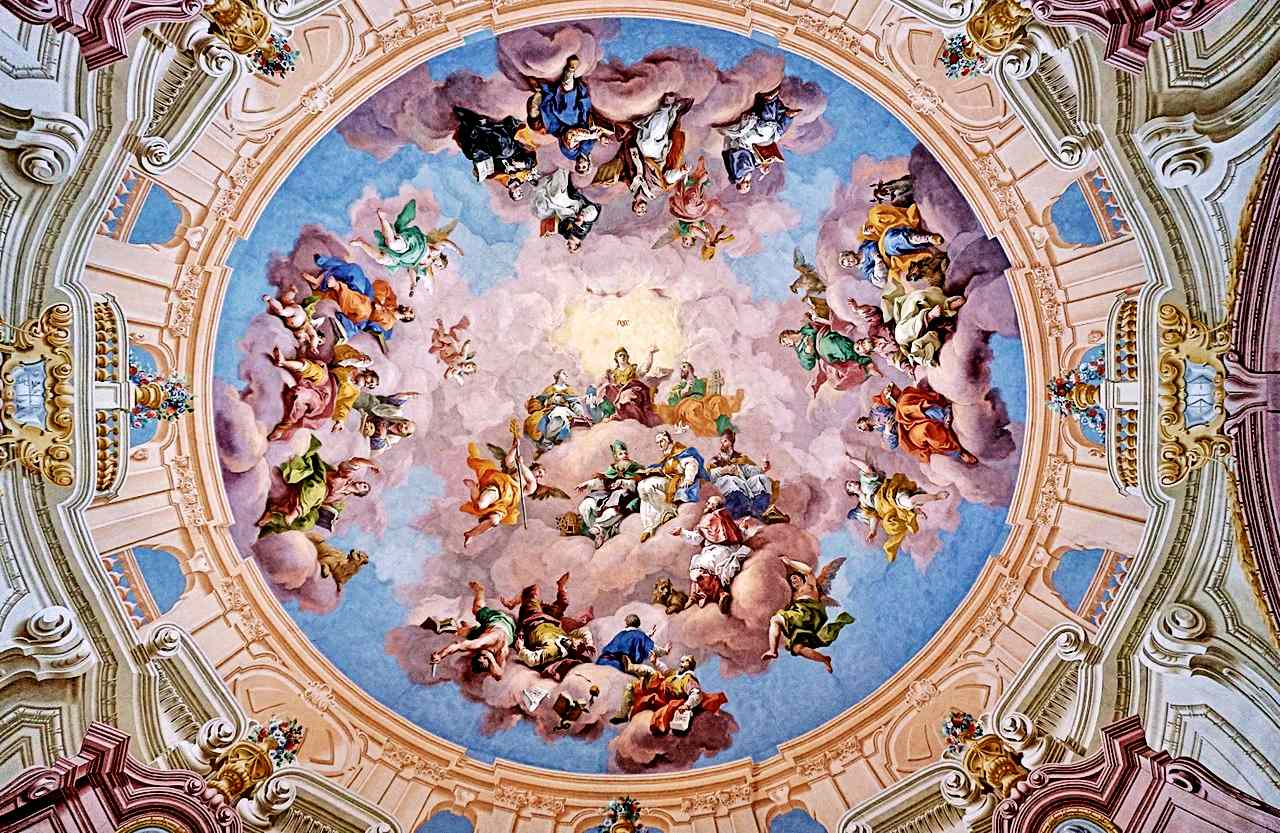

- The famous main hall of the library is one long, wide corridor consisting of seven consecutive rooms, each topped by a dome;

- Each of the seven domes is decorated by frescoes with themes relating to the progressive illumination of the human mind up to the highest point of enlightenment, namely, Divine Revelation, which is the center dome;

- The four decorative pillars that hold up the central dome have bronze statues attached to them symbolizing the Four Last Things: Heaven, Hell, Death and Judgment; and

- Most of the books of the Admont Library are in rooms adjacent to the central hall and accessible through passages between the tall stacks of books.

Despite its relatively “young” age compared to its monastery, the library has its own history to tell. In 1865 a catastrophic fire destroyed the entire Abbey, but, providentially, the library remained unscathed by the blaze except for a little water damage.

When the Nazis entered Austria in 1938, they closed the Admont monastery and expelled all the monks. Again, providentially, nothing of the library was lost or damaged during those years (1938-45), and the Benedictines returned after the Nazi defeat to take possession of their great gift once again.

The Most Fascinating Part

To me, the exquisite beauty, the dedication to learning, and the story of survival are all wonderful, but they are not the best part of the library’s story. The best part is about people, not books.

Among the archives kept in the Abbey are literally thousands – I do not exaggerate – of humble parish register books from over four hundred churches in the surrounding region of central Austria where Admont has had its greatest influence for over ten centuries. True to form, the register books have been preserved by the monks and are now all documented, photographed, and archived on the Library website (albeit entirely in German!).

These registers offer an astounding window into the history of an entire nation. Anyone who happens to have ancestors from Central Austria (the region of Styria) in the last four centuries could look up their names and find them as they were originally handwritten into the baptismal registers of the churches preserved by the Abbey.

With Teutonic efficiency, the books, some going back to 1600, are catalogued by the names, founding dates, and locations of the parishes (with photos of current day churches!); and by alphabetical/chronological listings of the names of all the souls who received sacraments in the Catholic evangelization of Central Austria during the last four centuries.

It has to be the library’s most precious collection of all because it’s a story of the people the Church has shepherded into the Kingdom of God.

All of this brings us back to the founder of Western monasticism. While St. Benedict’s sons have been unrivaled in preserving books, manuscripts, cultures, and civilizations, they never seem to have forgotten the essential mission of St. Benedict and work of monks: the salvation of souls.

Four More Benedictine Libraries

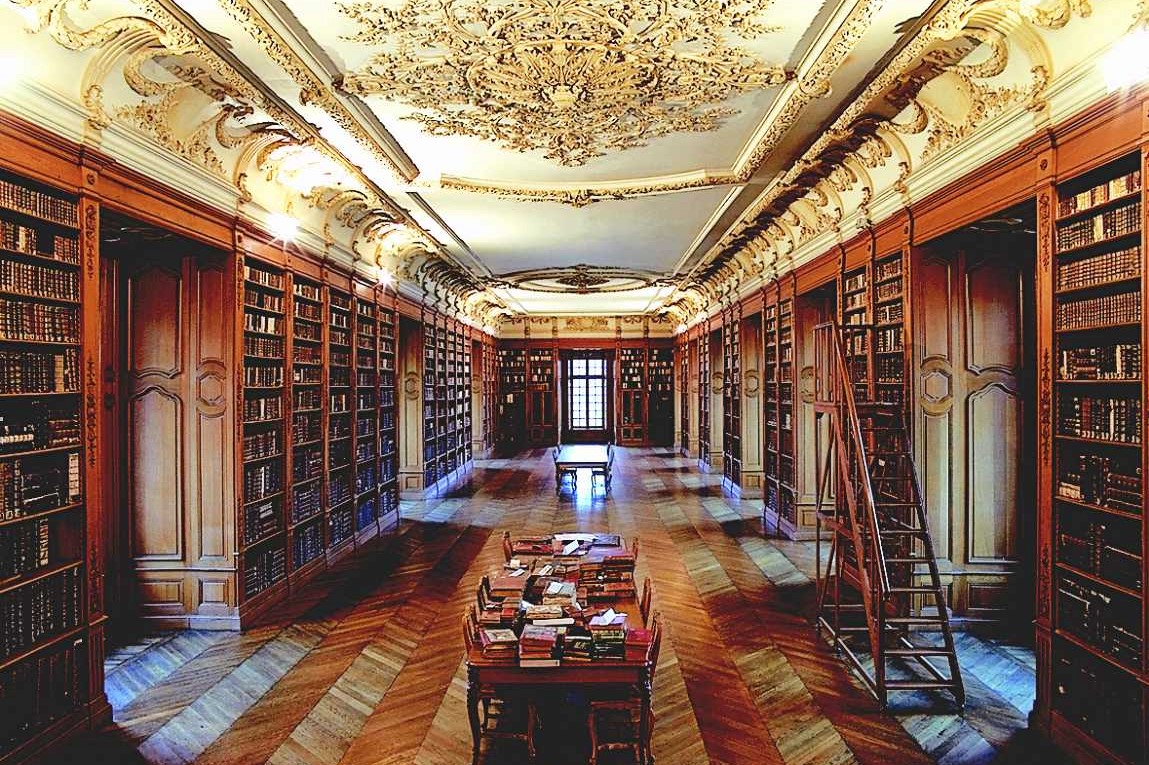

For your viewing pleasure, here are four more breathtaking monastic libraries among the hundreds of others I could have added. All are Benedictine creations, with the names and founding dates of the monasteries below the pictures.

Metten Abbey, Bavaria, Germany, 766 AD

Pannonhalma Abbey, Hungary, 996 AD

Saint-Mihiel Abbey, Lorraine, France, 709 AD

Wiblingen Abbey, Black Forest, Germany, 1093 AD

[Images courtesy of Jorge Royan via Wikimedia Commons and Admont Abbey Library.]

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 5/01/22, so it does not end with the regular Soul Work section. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

[…] Sacred Windows newsletter, I featured the magnificent library in the Benedictine Monastery of Admont, Austria. An institution like that is one of a huge network of Catholic monasteries in Germanic countries […]

[…] in which I marveled at the amazing grace of the Order of St. Benedict. Their extraordinary monastic libraries dotting the landscape of Europe symbolize the ancient order’s contributions to the world’s […]

how were these masterpieces built over a thousand years ago? without any modern machinery and could not be duplicated today

Hi Tony, They are true wonders of the world, aren’t they?! We have amazing technology today, but these buildings are the product of societies of faith. We pray for a renewal of that same faith for our time and our world! God bless you. Peter D.