Some months ago, one of my best Sacred Windows readers (among so many marvelous readers, assuredly!) asked me a very interesting question. He wondered when Christ opened the gates of Heaven.

The answer to that question is not as easy as one may think, but it is a natural and logical question because those little troublemakers, Adam and Eve, had closed off mankind’s access to paradise long ago. (I intend to have a talk with them about that some day).

Paradise Lost

After the expulsion, the Just God would only open the gates when sufficient atonement for humanity’s sins had been made. Man could not storm his way into heaven, even if he were righteous.

In fact, that was the cause of the question. My friend was struck by the comment I made in an article about St. Joseph that even the saintly foster father of the Son of God could not enter the heavenly realm until Christ had opened the gates for him. That’s pretty astounding, when you think about it.

In fact, that was the cause of the question. My friend was struck by the comment I made in an article about St. Joseph that even the saintly foster father of the Son of God could not enter the heavenly realm until Christ had opened the gates for him. That’s pretty astounding, when you think about it.

So, the question arises: After Christ’s sacrificial death, when did He open the gates of heaven so that all redeemed souls could enter?

We have several logical choices. Either He opened the gates of heaven

1/ Immediately after His Death, 2/ At His Resurrection, or 3/ At His Ascension.

All are plausible, but only one is correct. Let me explain.

The Good Friday Theory

Some have speculated that Christ’s Death, which caused an earthquake and eclipsed the sun, was so powerful that it must have opened the gates of heaven. One of the occurrences on that day seems to support that theory.

When our Lord died, the curtain in the Temple was mysteriously torn in two (Mt 27:50-51). Wow, if that doesn’t seem like a sign of opening, I don’t know what is.

When our Lord died, the curtain in the Temple was mysteriously torn in two (Mt 27:50-51). Wow, if that doesn’t seem like a sign of opening, I don’t know what is.

The actual effect of the curtain’s tearing, however, was the abrogation of the Old Covenant, whose ritual sacrifices would be brought to a violent end with the destruction of the Temple by the Romans in 70 AD.

In other words, the torn curtain signified the closing of something, not the opening of heaven.

The Descent to the Dead

Then, there is one of the most mysterious and fascinating passages of Scripture. In the First Epistle of Peter, the Apostle claims that Jesus actually descended to Sheol (or Hades) after His death.

In our Creed, we say “He descended into Hell,” but this term is synonymous with the Jewish understanding of Sheol, the realm of the dead before Christ came. It is not the Hell of the damned of later Christian theology.

Here’s the scriptural reference. St. Peter said:

“Put to death in the flesh, he was brought to life in the spirit. In it he also went to preach to the spirits in prison who had once been disobedient” (I Peter 3:19-20).

Preach to the spirits in prison?

Preach to the spirits in prison?

The Church has always understood this to mean that on Holy Saturday, Jesus descended into Sheol to preach the Good News to those souls who had died before Him and were awaiting salvation. It is unthinkable that God in His great mercy would have let those souls languish in darkness for all eternity.

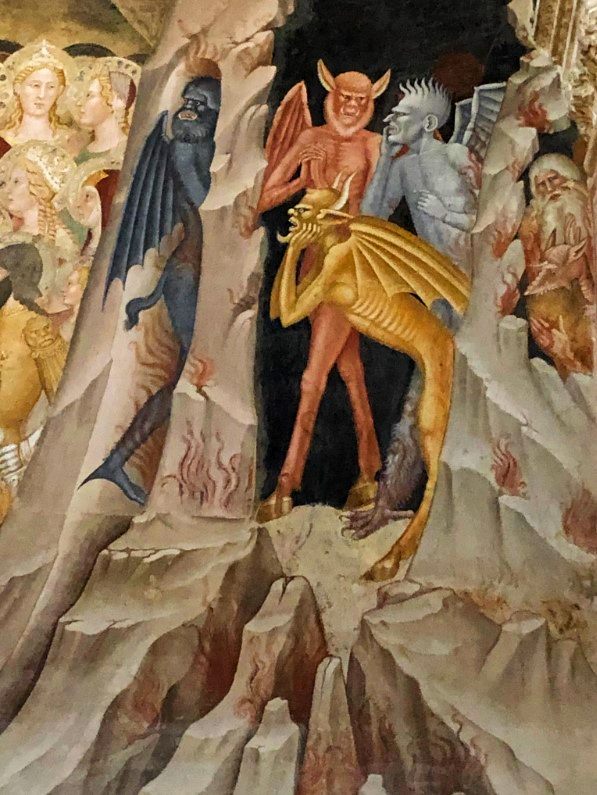

We don’t have much biblical information about it, but our religious intuition tells us there was nothing positive about the place. You may recall the frightening message that Dante placed over the gates of death in the Inferno (ca. 1325 AD):

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.”

Who would dare go there voluntarily? The theory was that the only person who could enter the realm of death unopposed was one who had no stain of Adam’s sin. (The sinless Virgin Mother of God could not go there simply because she had not died yet.)

In a word, only the unblemished Lamb of God, sacrificed for our sins, could walk through those gates unopposed.

What St. Peter describes in so few words is actually the ultimate rescue story, a tale that plays out more vividly than a Hollywood thriller. The traditional English term that has been assigned to that event may be familiar to you:

The Harrowing of Hell

The scene was harrowing all right. In the Tradition, Sheol was envisioned as a giant fortress, menacing in its hopelessness. Death had devoured Adam and Eve and locked them away with all their sinful children behind its forbidding gates.

Again in Dante’s Inferno, the poet Virgil guided Dante into the realm of the dead. When the two arrived at the entrance, they saw that those seemingly impenetrable gates had been totally shattered, hanging off their hinges, never to be repaired.

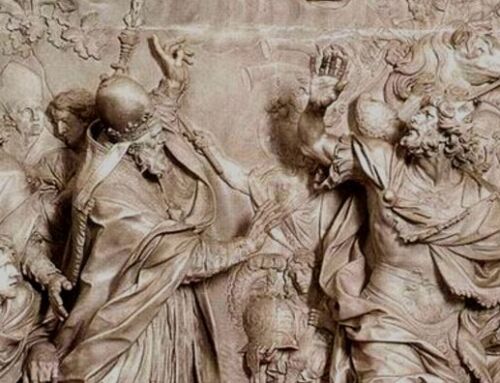

In the Renaissance fresco below (The Harrowing of Hell, by Andrea di Bonaiuto, from the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence), the Lord stands on a huge gate that has been torn off its hinges and pins the devil underneath it! At right, a few little demons cower behind a wall.

As Dante described it, the gates looked as though some great force had emerged from inside of Sheol blowing the gates apart as it exited. That idea is not biblical, as such, but it’s great artistic imagination, isn’t it?

The power that broke the gates from the inside was the Man-God Himself who was “swallowed up in death.”

The Cross as Bridge

St. Ephrem the Syrian (306 – 373 AD) is undoubtedly the most eloquent witness to this tradition. Here is part of his radiantly beautiful Easter Sermon:

Death trampled our Lord underfoot, but he in his turn treated death as a highroad for his own feet. Death slew him by means of the body which he had assumed, but that same body proved to be the weapon with which he conquered death.

Concealed beneath the cloak of his manhood, his godhead engaged death in combat; but in slaying our Lord, death itself was slain. It was able to kill natural human life, but was itself killed by the life that is above the nature of man.

Death could not devour our Lord unless he possessed a body; neither could hell swallow him up unless he bore our flesh; and so he came in search of a chariot in which to ride to the underworld. This chariot was the body which he received from the Virgin; in it he invaded death’s fortress, broke open its strongroom, and scattered all its treasure.

Such beauty! It seems clear, then, that in accord with God’s eternal plan, Christ chose not to open the gates of heaven until He had first shattered the gates of hell. The final image of St. Ephrem’s Easter sermon is utterly wonderful:

He who was also the carpenter’s glorious son set up his cross above death’s all-consuming jaws, and led the human race into the dwelling place of life. We give glory to you, Lord, who raised up your cross to span the jaws of death like a bridge by which souls might pass from the region of the dead to the land of the living.

(A creative modern rendition by Elizabeth Wang.)

One final thought: Christ’s heroic act also gives new meaning to the spiritual power He gave to the Church before He died: “And so I say to you, you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it” (Mt 16:18).

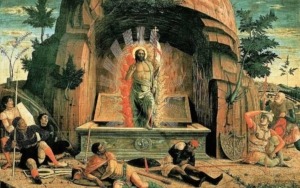

The Resurrection Theory

But even His triumphant rising from Sheol did not open the gates of heaven because the Resurrection brought Him back to earth, not heaven. The twin events of the descent and rising of Christ had their own distinct meaning in salvation history.

The downward journey into Sheol brought about the total defeat of mankind’s mortal enemy: the Devil. Jesus had “bound the strong man” (Mt 12:29) and put an end to the enemy’s tyranny over humanity. The upward movement of the Resurrection sealed Christ’s victory.

By means of these divine acts, He established His sovereignty over all things in the universe. St. Paul said that to Him “every knee should bend, of those in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (Phil 2:10). Amen!

The Ascension Theory

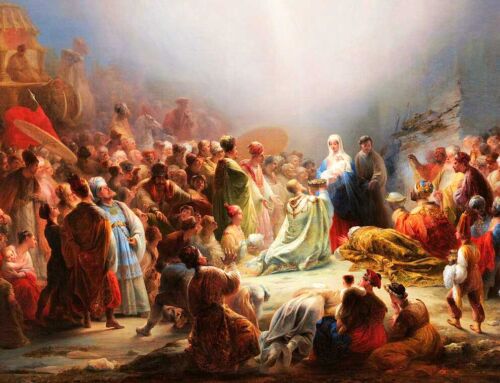

There was only one thing left for Christ to do, which brings us to our final point. He had to return to His Father with the spoils of victory.

Theologically, it makes the most sense that the gates of heaven were opened only when He went there personally and brought all those redeemed souls with Him. In addition to St. Luke’s accounts of the Ascension (Lk 24:31; Acts 1:9), St. Paul testifies to this mighty event:

What does “he ascended” mean except that he also descended into the lower [regions] of the earth? The one who descended is also the one who ascended far above all the heavens, that he might fill all things (Eph 3:7-10).

We have further biblical testimony to this, but from the angelic point of view. Here we have to suspend literal interpretations and embrace the following as a poetic explanation of an unfathomable mystery:

O gates, lift high your heads, grow higher, you ancient portals, that the king of glory may enter! (Ps 24:7)

The Fathers of the Church interpreted this particular passage as the clamor of the angels of earth who escorted the glorious King to His coronation in heaven. It reads almost like a parlay between two military forces meeting each other at the gates of a mystical fortress.

Ascending in His vanguard, the angels of earth called out to the angels of heaven, ordering them to open the mighty gates for their conquering King.

But apparently, the heavenly guardians didn’t recognize this King because the Second Person of the Trinity had taken on a human nature, so they asked:

“Who is He?”

And the angels of earth responded back with a proclamation verifying His identity:

“The Lord, strong and mighty, the Lord, mighty in war. He is the Lord of Hosts, he is the king of glory” (Psalm 24:7.10).

What a mystery: At the Resurrection, the humans didn’t recognize their Lord, and at the Ascension, the angels didn’t recognize Him either! He was transformed by glory.

But it was their Lord—this King of Glory—who was now bringing human nature itself into the heavenly realm. Nothing like that had ever been seen in heaven before!

Though the angels were astonished at the sight, they immediately knew what to do. In one fell swoop, they flung open the gates of heaven so that the mighty, conquering King could enter with all the souls He had won for His Father!

Oh, what I would have given to be there when the King of Glory entered heaven amid shouts of joy on the day of His Ascension!

———-

Feature Image by Dennis Gries from Pixabay; Via Wikimedia Commons: Expulsion of Adam and Eve (Benjamin West, 1791); Resurrection (Andrea Mantegna); Christ Rescues Adam and Eve (Circle of Albrecht Durer); The Harrowing of Hell (S.M. Novella, Andrea di Bonaiuto); Gustave Doré (Ascension).

Leave A Comment