Mother Teresa of Calcutta was largely known for her work in India, so we tend to forget that she was born in the tiny Eastern European county of Albania. What many also may not realize is that Albania was the first country in the world to establish atheism as its official state religion.

Albania’s history is a study in paradox. As part of the Byzantine Empire it has the singular distinction of being part of the first area on the European continent to accept Christianity under Emperor Constantine (325 AD). But, over several centuries, the area became a majority Muslim state, the only one in Europe. Albania did not become an independent nation state until after World War I.

The lives of Albania’s two most prominent citizens reflect this small country’s deeply paradoxical history.

A teacher became a tyrant …

Enver Hoxha (pronounced Hodja), born in 1908, was the man responsible for Albania’s woes. His father was a Muslim cloth merchant, but Enver took another route. He chose to be a teacher. After WW I, however, he became embroiled in the politics of the day. He dedicated himself to propagating Marxism of the brutal Leninist-Stalinist type that took Old Europe by force after the folly of the Great War.

Hoxha’s political history is complex and quite interesting. It is also extremely sad for anyone who laments the destruction of many once-great civilizations by Communism. Albania, thanks to Hoxha, was one of those countries that was totally overrun by the forces of evil. He became the absolute ruler of Albania when he and his Communist Party seized power after World War II.

Hoxha immediately conducted a purge of at least 400 of his political enemies whom he ordered to be murdered between 1946 and 1950. It was the first of two major purges of leadership he would undertake (the other occurred in 1974). The purges, among other reasons, are why Hoxha is sometimes called “the Iron Fist of Albania.”

… and turned Albania atheist

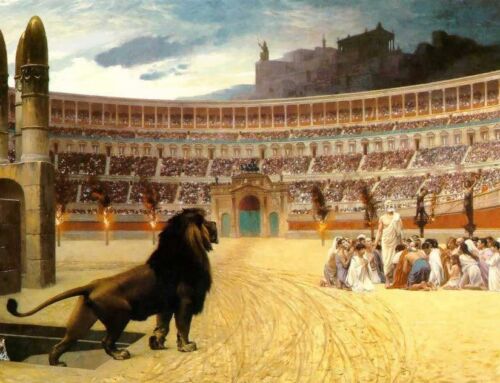

During his 41 years of absolute power, Hoxha turned Albania into the world’s first and only exclusively atheist state. He completely outlawed religion – which even the Soviet Union did not do. He closed all churches and mosques (2,169 of them), murdered 100,000 people, and killed all but 30 of the 300 priests in the country.

The heartless Hoxha even denied Mother Teresa re-entry to her native country, claiming that she was a dangerous and subversive agent of the Vatican. He prohibited her from visiting her aged mother and sister before their deaths and would not let Mother Teresa’s relatives leave Albania to visit her elsewhere.

Hoxha died in 1985 after forty-one years of tyranny, and typical of Marxist tyrants, he left his country the poorest in Europe. His mausoleum in Albania’s capital city of Tirana was a bizarre-looking white pyramid that has since been converted to a museum for tourism.

Hoxha’s corpse was disinterred in 1992, after the fall of Communism, and was removed to a cemetery on the outskirts of the capital. He is buried in an unmarked grave.

From the heart of Christian Albania

But Albania produced more than just a mass murder. It produced a saint in the person of Agnes Gonxha (pronounced Gondja), later known to the world as Mother Teresa of Calcutta. She was a contemporary of Hoxha, born only two years after him, but her life took a very different path.

Like virtually all Albanians of that era, her family circumstances were poor and disadvantaged. Her father was a businessman but died when Agnes was only eight years old.

At age eighteen, the pious girl left Albania for Ireland to pursue a religious vocation. In Ireland, in 1931, she joined the Institute of the Blessed Virgin Mary, known as the Sisters of Loreto. She took her final vows in 1937, just a few years before Hoxha founded the Albanian Communist Party.

Another teacher became a missionary

Like the young Enver Hoxha, Mother Teresa was also a teacher. But in 1946 Mother Teresa had a mystical vision on a train in which she perceived the crucified Christ saying, “I thirst” (John 19:28). She understood that image ultimately as Christ’s call for her to serve “the poorest of the poor” in India. In 1948 she founded the Missionaries of Charity to carry out that mission.

Her religious order was soon overflowing with women who wanted to dedicate themselves to the service of Christ in the poor. The order now has 4,500 nuns, and Mother Teresa has a reputation as one of the greatest humanitarians of the 20th century. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 for her work.

It is hard to believe that the small country of Albania produced both an Enver Hoxha and Mother Teresa. Where Hoxha left a legacy of emptiness and evil, Mother Teresa left an international legacy of goodness.

Darkness and light

The lives of these two Albanians are remarkable in their parallels and contrasts. If we are not too literal about the comparison, it seems that they could be a mirror image of each other.

The dictator and the saint were born two years apart on opposite sides of the same country. Both were school teachers early in their careers. Each of them founded an institution that would have a massive impact for good (a religious order) or ill (an oppressive political party) on millions of people.

The picture of their respective ascents to positions of authority is also a very interesting study in contrasts. While Hoxha was seizing and solidifying absolute political power over a suffering people, Mother Theresa was experiencing Christ’s call to found a religious order to assist the most hopeless suffering souls on the face of the planet. For each of them, the critical time period was 1946-1950. Hoxha had killed all his rivals by 1950. The Missionaries of Charity received Vatican approval in the same year.

Their contrasting styles of leadership – iron-fisted tyranny versus poverty and humble service – reflect, in an absolute way, the values of Satan versus the values of Christ.

Enver Hoxha ruled as dictator and is now largely forgotten. Mother Teresa died in 1997 after fifty-one years as head of the Missionaries of Charity and is now a canonized saint whose tomb in Calcutta is visited by millions of pilgrims each year.

The contrast between darkness and light could not be more striking.

Lord of history

What conclusions are we to draw from this paradoxical picture of a dictator and a saint from the same land? Several.

“God will not be mocked” (Galatians 6:7):

In addition to his use of oppressive power, Hoxha made himself into an idol. He set up statues of himself all around the country and demanded total religious obedience. The “atheistic state” was the religion he forced on everyone with himself as its god.

St. Paul tells the Galatians that God ultimately controls human history, and every idol and false system of worship raised against Him will fall.

Evil has power but never authority:

We cannot deny that evil has real power to do lasting damage. Hoxha closed and tore down churches, killed thousands, and abolished Christian education. Millions of people’s lives were turned upside down by the coercive will of one man. Yet, history shows that no one ever loves a tyrant.

Dictators have power but no authority to transform lives and hearts. Evil rearranges the furniture of a society (a business, an institution, etc.) as it sinks into nothingness. Only love and virtue rearrange the inner life of man and raise him up.

Light conquers darkness:

When you walk into a darkened room and turn on a light, the darkness immediately recedes. The same is true in the spiritual world: where light enters, the darkness cannot remain.

Albania reverted to democracy after the fall of Communism, in the early ’90s. Only 2.5% of its population professes atheism today. People are now free to worship something other than Enver Hoxha. Over 57% of Albanians are Muslims and about 17% are Christians. The rest are of different faiths or are undeclared. The light of Christ is not fully shining in that small country of three million, but its prospects for the future are much brighter than during most of the 20th century.

Great good comes out of great suffering:

The Cross of Christ teaches us that something good always comes out of human suffering. But the grace that flows from Calvary does not undo the destruction directly. Grace is usually poured out elsewhere. This is certainly the case with the little Albanian nun who evangelized the entire world out of a homeland that she was forbidden to visit.

Albania’s recovery from forty years of Communist dictatorship is not finished; the damage to that ancient Christian society was real. But the world is now full of missionaries of Christ’s charity – all because of the little Albanian nun in the blue and white habit going around doing good to all.

The good you do today may be forgotten tomorrow. Do good anyway. ~ Mother Teresa of Calcutta

Soul Work

No one can repeat the heroic works of a saint like Mother Teresa, but everyone has a gift to offer the world. Mother Teresa’s deep faith and charity touched even the most hardened hearts because these spiritual gifts always bring light to others when they are shared.

In our concern for the temporal wellbeing of those we love, it is easy to lose sight of the spiritual values that they need more than food to sustain their lives.

Do the people around you know where your deepest loyalties lie? Are you forthright in professing and offering your Christian faith, even to your own family?

Perform some work of goodness today for another person. Do it for no reason other than sincere charity. “Give until it hurts”, as Mother Teresa used to say, and you will be the light in someone else’s darkness.

https://skokowe.pl https://skokowe.pl https://Prestigeitaly.pl/