The Solemnity of St. Joseph on March 19th made me think of the monumental St. Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal, Canada. Apart from it being the world’s largest shrine dedicated to the foster father of Our Lord, the Oratory is also the largest Art Deco church in the world.

The Solemnity of St. Joseph on March 19th made me think of the monumental St. Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal, Canada. Apart from it being the world’s largest shrine dedicated to the foster father of Our Lord, the Oratory is also the largest Art Deco church in the world.

Art Deco! The very name inspires nostalgia for a lost era of quality art and one on which American artists had a significant influence.

This river of intriguing art, like so many in the vast ocean of human creativity, was often used to glorify man. However, St. Joseph’s Oratory (basilica) enlists Art Deco in the work of glorifying God! But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We need some background.

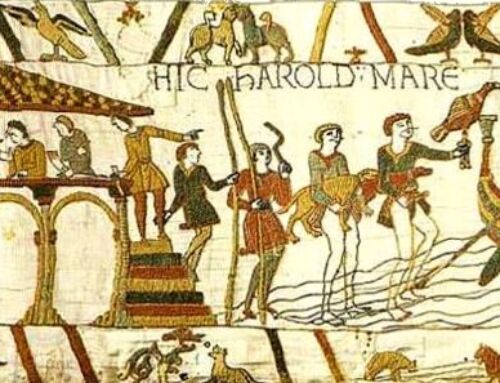

It’s often hard to distinguish Art Deco from the style of Art Nouveau. Historian, Paul Johnson, says the two were essentially on a continuum, with Art Deco coming later and enhancing the former in significant ways. The First World War intervened between the two movements so that we can see them as distinct styles.

that were at their heights around the same time (see my earlier piece), it was a reaction to the classical styles and strictures of the art academies that had dominated art since the Renaissance.

that were at their heights around the same time (see my earlier piece), it was a reaction to the classical styles and strictures of the art academies that had dominated art since the Renaissance.

Artists always seem to want something new and provocative so Nouveau (French for “new”) became the moniker and rallying cry for the breakout movement, which, despite its French name, was international from the beginning. Here are Art Nouveau’s distinguishing features:

- Return to nature and natural forms (vs. the “posed” settings of classicism)

- Curves, graceful lines, and decorative flourishes

- Sedate colors

- A love-hate relationship with technology (that is, attempting to incorporate modern materials and structures into art)

It would be impossible here to do a survey of Art Nouveau designs, but we may be familiar with other examples: all the Tiffany furnishings, lamps, jewelry, and stained glass, for example, are quintessential Art Nouveau and were immensely popular at the turn of the 20th century.

Believe it or not, the famous Russian Faberge Eggs were all created in this style as well as the first design for the Coca Cola bottle!

You may recall that the late 1800s was also a time of economic and social upheaval called the Industrial Revolution. Today we live in an era of constant technological change, so we are used to the noisy intrusions of gadgets and machines into our lives. But Western societies of the late 1800s most certainly were not.

The Art Nouveau movement reacted to the Industrial Revolution in a kind of schizophrenic way. On the one hand, artists “went back to nature” in response to the dehumanizing forces of factories and machines.

The Art Nouveau movement reacted to the Industrial Revolution in a kind of schizophrenic way. On the one hand, artists “went back to nature” in response to the dehumanizing forces of factories and machines.

On the other hand, machines were increasingly infiltrating social life, so artists made an uneasy compromise and sought to fuse new technological forms with art, though not very successfully. I love those fancy entryways to the Paris Metro stations (all created in this era), but, as you can see, they are a bit awkward as art.

On the other hand, machines were increasingly infiltrating social life, so artists made an uneasy compromise and sought to fuse new technological forms with art, though not very successfully. I love those fancy entryways to the Paris Metro stations (all created in this era), but, as you can see, they are a bit awkward as art.

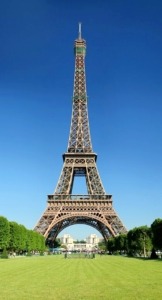

To the extent that we can call the Eiffel Tower a work of art—it sort of is—we can see the influence of an artistic movement like Art Nouveau on technology. It was built for the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris and was a new expression of smooth iron curves, lines, and flourishes worked into a massive piece of architecture.

But from even before the turn of the century (1900), Western culture had seen the development of the car, the radio, the telephone, the airplane, and every form of advancement in construction and architecture, and these soon became a way of life.

All of these new forces were put to use in one way or another during the First World War, which was the first modern technological war in a strict sense, quite different from the Napoleonic wars of just a century earlier.

All of these new forces were put to use in one way or another during the First World War, which was the first modern technological war in a strict sense, quite different from the Napoleonic wars of just a century earlier.

These advancements also set the stage for the Roaring Twenties, when the US emerged from its wartime malaise and experienced an unparalleled explosion of wealth and luxury. By this time, society had simply abandoned its love-hate relationship with technology.

Artists of the Art Deco period (1920s up to the Second World War) breezed easily through this massive industrial change by aiming to fuse technology with art. In this, they were quite successful.

Incidentally, the name “Deco” derives from a 1925 Art Fair in Paris called the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts. At the time it was called le style moderne but only later did the term Art Deco get applied to the whole genre of art.

If Art Nouveau tried to marry technology with nature, Art Deco essentially made brutish technology fashionable. It is really one of the most incredible periods of art in all of history. Here are Art Deco’s distinguishing features:

If Art Nouveau tried to marry technology with nature, Art Deco essentially made brutish technology fashionable. It is really one of the most incredible periods of art in all of history. Here are Art Deco’s distinguishing features:

- Streamlined look and simple, clean shapes

- Straight lines and stylized, geometrical forms (imitating fancy machines)

- The use of man-made substances combined with natural materials

To these, I would add that the style tended to feature mythological themes and also incorporated many bright colors and bold letters into all its designs. Technology even became part of the art itself (the ubiquitous skyscrapers and clock towers, for example).

There are way too many examples from this period to cite even a small sampling, but everyone who has ever watched a Batman movie probably knows what the top of the Art Deco Chrysler Building in New York City looks like.

There are way too many examples from this period to cite even a small sampling, but everyone who has ever watched a Batman movie probably knows what the top of the Art Deco Chrysler Building in New York City looks like.

Its aluminum cap was utterly unique for its time, not to mention the gargoyle-like structures on the 61st floor (lower right corner) that look like Eagles. They are said to represent Chrysler hood ornaments! See what I mean about the fusion of technology and art?

[Check out this great page of original photos of the Chrysler Building.]

On that subject, the decade of the 20s was the era of the classic skyscraper, and Art Deco made it an indelible feature of city skylines, or at least a truly stylish feature. All you have to do is to Google the term “Art Deco Skyscrapers” to see how many of these went up in that era.

The prosperity of the Roaring Twenties made fancy skyscrapers a thing, but then the Depression made them a thing of the past. Here are a few fabulous ones:

The Guardian Building, Detroit

Carbon & Carbide Building, Chicago

Am. Radiator Bldg, Manhattan, NYC

City Hall, Los Angeles, California

There is also a whole town in America that can literally be called an Art Deco enclave: the glamorous Miami Beach. It’s one of a kind.

The Great Depression turned sleepy Miami Beach into an exotic haven to escape to in the late 1920s and 1930s, and it still is an idyllic place. One gets a deep sense of nostalgia and elegance when walking through the historical district in Miami Beach, which is usually just referred to as the Art Deco District.

More than 950 Art Deco style buildings were built in that era and are all well-preserved today thanks to a number of laws passed in the 1970s mandating their preservation and upkeep. Here are a few of the real gems—all hotels—in which the Great Gatsby might have frolicked:

The Breakwater

Leslie Hotel

Casablanca & Majestic

The Ocean Five

Hotel Riviere

The Waldorf Towers

Ultimately, houses of worship were affected by the artistic trend because church building, too, flourished in the 20s. And even though Art Deco always remained a sort of avant garde movement for churches, some communities built magnificent Art Deco churches in America.

The most notable of the Catholic varieties are the National Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan and the Madonna della Strada Church perched on the edge of Lake Michigan in Chicago.

I had occasion to go to the Little Flower shrine when I was a youth to receive a Scouting religious award. I remember the ceremony, but at that age, I couldn’t really appreciate the amazing artistry of the church I had entered. Look at that tower!

(The statue carved into the corner is a Roman Centurion standing guard at the foot of the Cross. Mary Magdalen stands behind him.)

I could go on forever about Art Deco, but I’ll end as I began, with a few words about St. Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal. It was the vision and passion of a humble Holy Cross brother, Andre Besset, CSC (1845-1937, canonized in 2010). He wanted to become a priest but was of such frail health that the order would only allow him to become a religious brother.

This man knew his mission. His room faced Mount Royal, and for years he prayed to St. Joseph for a shrine there. He regularly climbed the Mount with a friend and embedded medals of St. Joseph on the hillsides so as to informally consecrate the land (which he didn’t own!) to his great Patron.

Although the actual owners of the property for years refused to sell the land, some mysterious and miraculous turn of events made them amenable to the sale, and by the end of the 1800s, the Holy Cross Order owned the entire top of the mountain!

The building project didn’t begin until 1914 due to fundraising and planning. And it would take another 50 years to finish the huge basilica, given that its construction spanned two world wars and the Great Depression.

Brother Andre at least lived to see the majority of the Oratory rise on Mount Royal. He died at the age of 92 in 1937, the very year construction began on the dome.

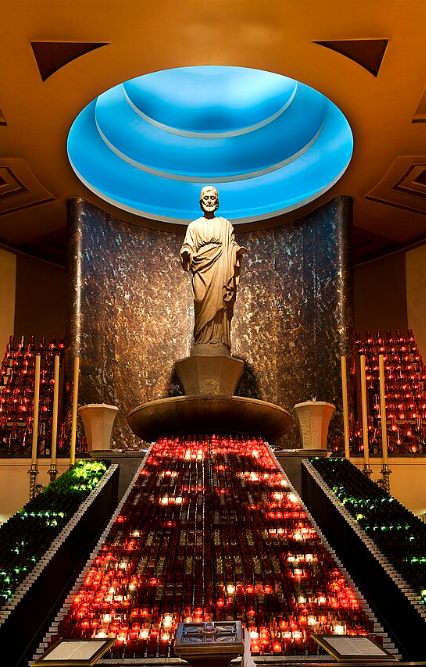

The exterior of the church looks like a Renaissance basilica (the dome was modeled on the Cathedral of Florence), but the interior is nicely done in the Art Deco style, though not flashy like the hotels and skyscrapers above. The decorum was apt for its purpose, which is worship.

Its massive dome rests on smooth-lined columns while some of the ribs of the vault (ceiling) are angular. Notice all the lines and geometric shapes in a few of its greatest features:

Given the charms and charisms of its great Patron, St. Joseph, and the tranquility of its environment, the Oratory is monumental in many ways, particularly in spiritual strength and pristine beauty.

As with all human creations, Art Deco emerges from its own time and radiates its own natural beauty which usually glorifies human ingenuity. But it becomes a sacred window when it is used to glorify God, something St. Joseph would approve of wholeheartedly.

—–

Photo Credits: Carbide & Carbon Chicago (MattHucke); Los Angeles City Hall (Michael J Fromholtz); American Radiator NYC (Jean-Christophe Benoist); Guardian Building Aerial (Funnyhat at English Wikipedia); Ocean Five (Stefenetti Emiliano); Riviere (StefenettiE); Casablanca & Majestic (Visitor7); Breakwater at night (Tamanoeconomico); Leslie (Visitor7); Shrine of the Little Flower: Exterior (Lrgjr72); Door (Nheyob); Tower base (Andre Carrotflower); Madonna della Strada: Exterior; Interior (hakkun); Tassel House Stairway (Henry Townsend); Chrysler Top (PortableNYCTours); Chrysler Eagle (Jason Eppink); Jewelry (Philippe Wolfers); Coca Cola bottle (Gavinmacqueen); Klimt The Kiss (Belvedere Museum, Vienna); Eiffel Tower (Benh Lieu Song); Metro Station (Iste Praetor); Tiffany wisteria lamp (Fopseh); Faberge egg (Miguel Hermoso Cuesta); Bird vase (Lalique); Oratory photos (Visit the Oratory website); Aerial; Front View with Statue; Brother Andre; Colors on wall; Blessed Sacrament Chapel (blue); Dome interior; 10th Station; St Joseph Statue with Angels; Crypt; Organ; Religious Ceremony; Statue with Candles.

—

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 3/23/24. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Leave A Comment