When you did arts and crafts in school as a kid, you probably didn’t realize you were following in a great tradition that began with a Medieval guild – or at least one that sought to imitate the works of the Catholic culture that gave birth to the guilds.

That tradition was called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England, which was begun in 1848 by three dynamic English artists named Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, and several companions.

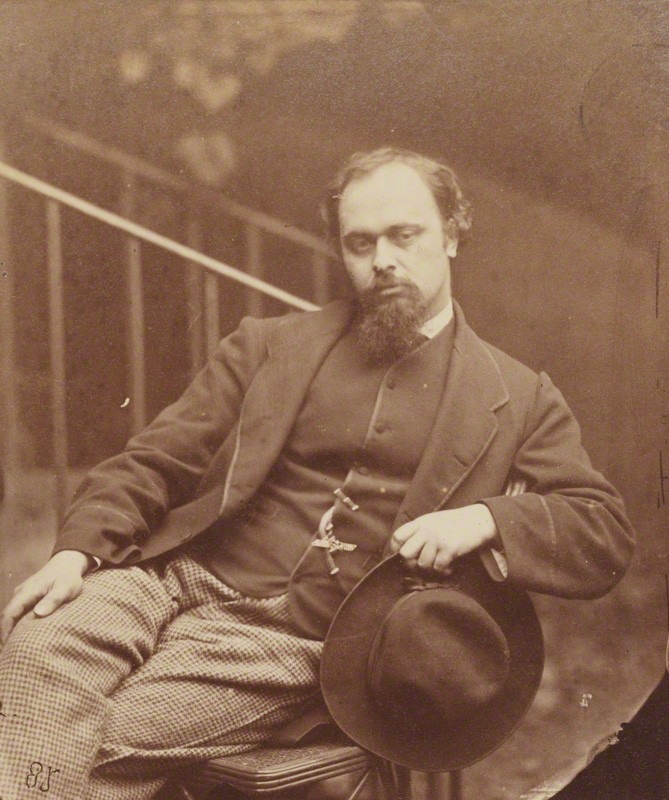

Rossetti

Hunt

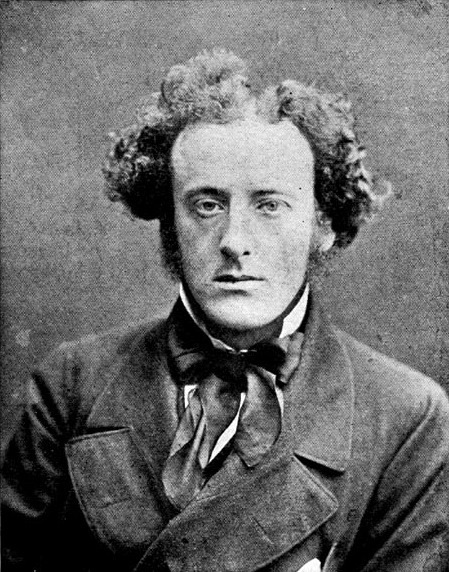

Millais

I know their brotherhood has kind of a strange name, but like all names, it has its roots in something real. These talented young men thought the art world of the time had become, well, boring and decided to do something about it.

Actually, it was a bit more particular than that. These young artists were rebelling against the Royal Academy of the Arts in London, which strictly enforced the classical artistic standards of the day and made it virtually impossible for anyone to be accepted in the art world without the Academy’s approval.

At that time, the painting conventions in England’s Victorian Age had become unimaginative and inflexible: mythological themes; predictable, stylized poses and settings; excessive concern with symmetry and proportion; fuzzy, bland colors, etc. (Similar to how my teenage niece describes the way I dress: boooooorrrring!)

The Brotherhood

So these three men formed their own artistic association as a sort of secret society (which they called a brotherhood, harkening back to a Medieval guild) and attempted to jump over three hundred years of art history and return to a style that was fresh and vibrant and relevant to the common man.

That explains their name. The group blamed the late Renaissance artist Rafaello for locking Eurpoean art into predictable classical themes and styles, so they proposed to go back to the early Renaissance and medieval artistic themes (i.e., “Pre-Raphael”) with their new style. It was a pretty ambitious endeavor, to say the least.

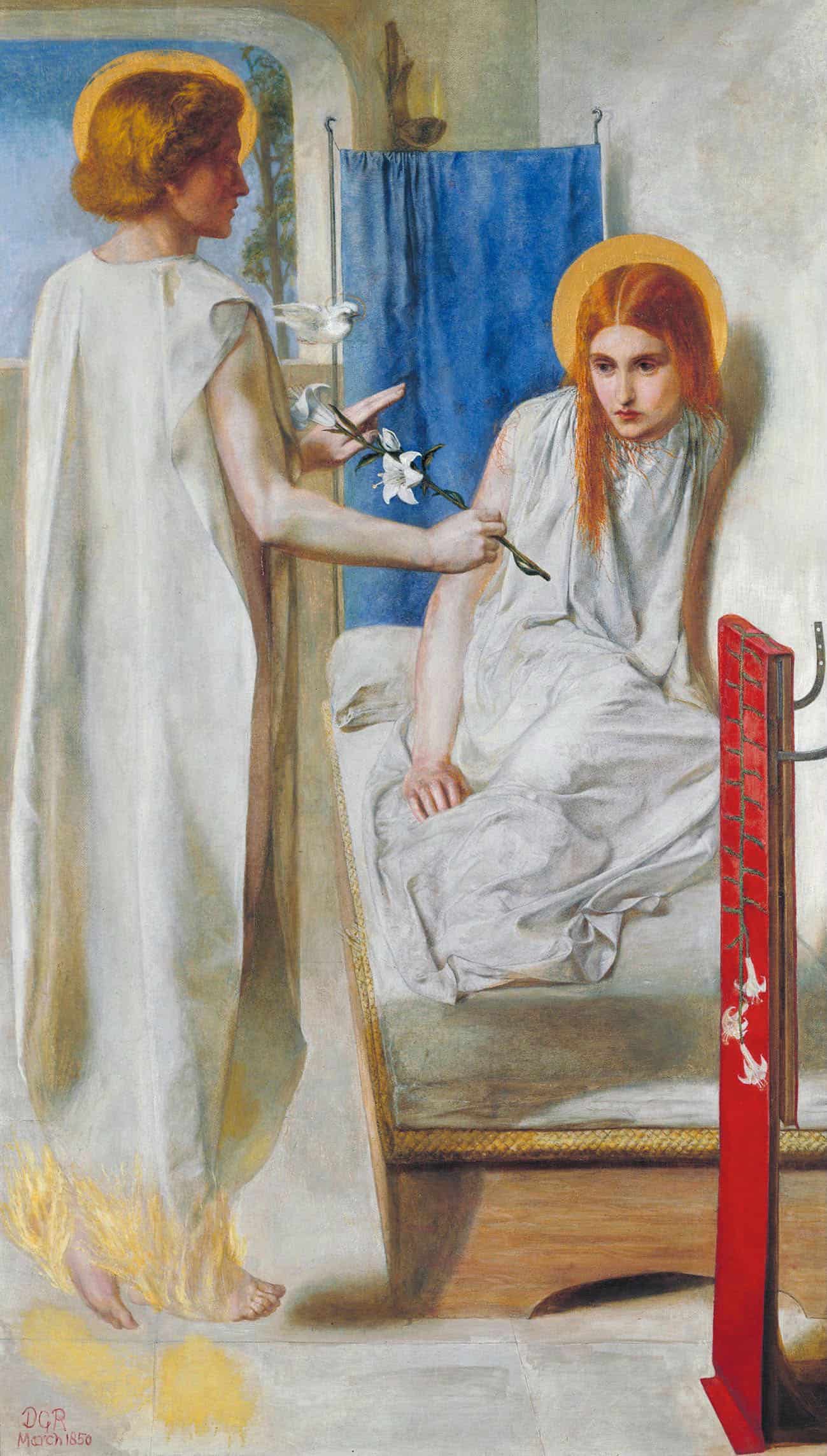

Their work had everything the old standards did not: astonishing color, clarity of presentation, real life themes, and vibrant moral (even overtly religious) messages. They wanted to get out of the game of painting noblemen and women in mythical or stagnant poses and return to the vibrancy of pure nature, lively spirit, and art that could be embraced and understood by commoners.

Want to see the difference? Here is a comparison of the two styles. The first is by Sir Joshua Reynolds, the founder and head of the Royal Academy of Art, and the second by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Brief style note: the Reynolds painting has the fuzzy aura of a Renaissance country scene with bland colors, staid outfits, and the formulaic triangular positioning of the group. There is absolutely nothing wrong with it as a painting, but the brotherhood didn’t wish to be confined to such conditions.

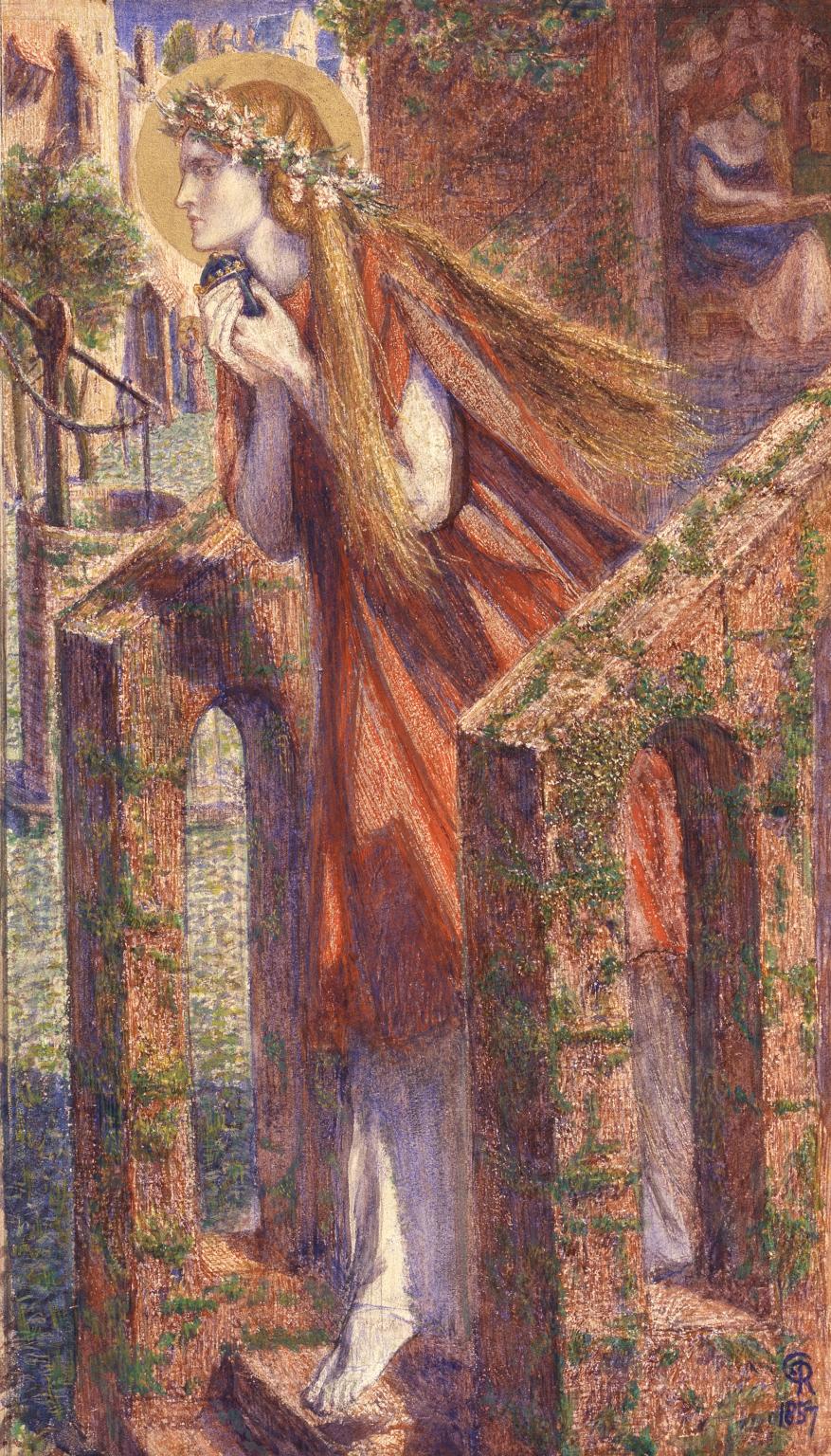

In contrast, there is nothing typical about Rossetti’s Joan of Arc painting (you knew I had to get Joan in somehow…). It comes across as crisp, vibrant, brilliant in color, thoughtful, and dynamically posed. It’s also a religious-type theme featuring not a member of the noble class but a saintly peasant figure of Church history.

Sequential Movements

The Pre-Raphaelites got started in England (their first exhibition was in 1849) just before the more famous Impressionist Movement began to flourish in France (begun in 1874). One can even make the case that the Pre-Raphaelites were the inspiration for the later French movement.

Not surprisingly, the Impressionists, too, were reacting against the hidebound artistic conventions of the day and the control over art that the Académie des Beaux-Arts exerted in their country. The differences between the two movements are fairly significant, though.

The Pre-Raphaelites returned to earlier forms of clarity, depth of color, and moral messaging which emerged from the totally Catholic context of the Middle Ages. That is, they set a rational and objective standard of beauty for their art. Ironically, most of them were not Catholic or even religious believers.

John Everett Millais— Joseph’s Carpenter Shop

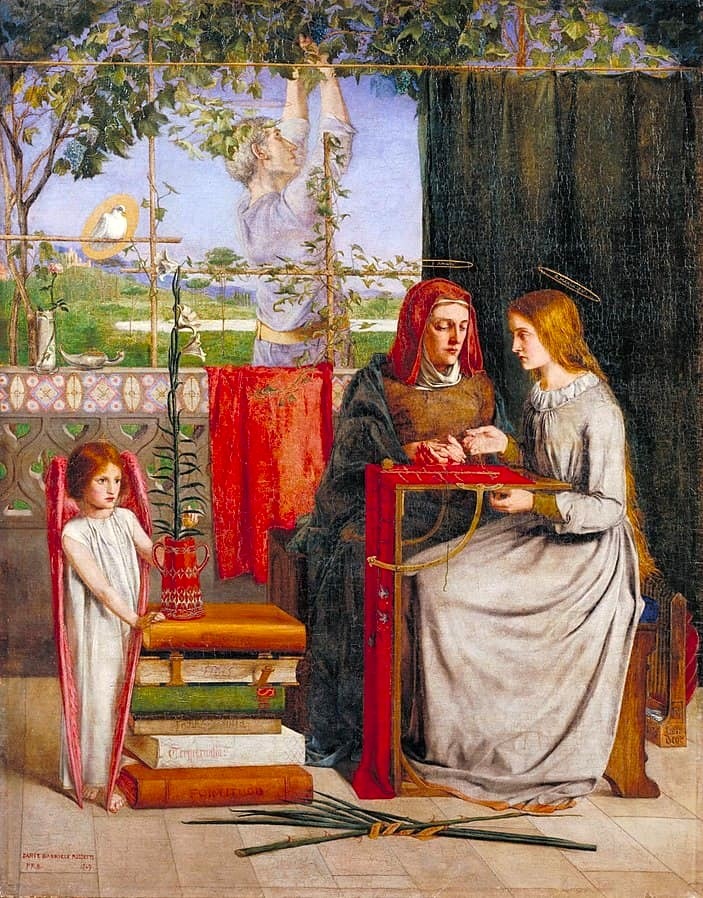

Rossetti - Education of the Virgin

The Impressionists, on the other hand, were interested in art primarily for the sake of free personal expression. Like their British counterparts, they loved vibrant colors and scenes that appealed to the common man, but unlike them, they chose to express beauty through completely subjective standards: namely, through the individual artist’s perception or experience of something.

The essential point I’ll make here is the one I’ve made elsewhere (“Is Beauty Really in the Eye of the Beholder?”) that when art is detached from objective standards of beauty, it soon degenerates into ugliness. That is what we can see with a comparison of the two movements, which both started well.

Pre-Raphaelites (Early)

Started with religious themes and realistic human scenes (1840s and 50s).

Experimented with realistic views of nature and vivid color.

Short-lived first generation of seven artists (lasted only until 1853 when they disbanded).

Impressionists (Early)

Started with scenes of Paris and views of the common man at leisure. The movement was almost completely devoid of religious themes.

Experimented with light and color and formlessness.

The fluid and fractured movement encompassed as many as 30 artists and lasted for 8 exhibitions between 1874 and 1886. Only one artist, Camille Pissarro exhibited in all 8 shows.

Two Artistic Pedigrees

At the risk of oversimplifying these complex realities, I’m attempting to explain only the broad strokes of each movement as they marched into the 20th century.

Here we can speak of a certain artistic pedigree of each movement as they developed over time, one was based on more objective criteria of beauty, the other based primarily on free expression. Here’s is how the movements developed in their later stages.

Pre-Raphaelites (Later)

Second generation (1860s through 1880s) delved into mythological themes quite heavily but never lost their passion for the common man and moral messaging.

Though most Pre-Raphaelites were painters, their number also included artists in other genres, indicating the movement’s depth of talent and influence:

- Literary critics (numerous members)

- Poetry (Rossetti’s sister Christina Rossetti wrote “In the Bleak Midwinter” immortalized in our beloved Christmas hymn),

- Sculpture (Founder Thomas Woolner crafted a statue of Captain Cook in Sydney, Australia)

The decorative arts, especially…

Second generation artists Wm. Morris and Edward Coley Burne-Jones and others expanded to church art, mosaics, frescoes, and stained glass.

Morris and Burne-Jones also created the Arts and Crafts Movement in England (see description below).

Impressionists (Later)

In the late 1800s, the movement skewed into subjectivist art trends, namely, the styles that exalted free expression and individual perception over traditional standards of beauty.

Impressionism quickly morphed into wildly different abstract art movements:

- Primitivism (Gaugin),

- Surrealism (Dali), and

- Cubism (Picasso), among others.

From these, abstract art morphed into other rather horrific art conventions:

- Bauhaus (Germany, boxy, purely functional);

- Art Brut (French, “raw” art by unskilled artists, sometimes called Art of the Mentally Ill); and

- Funk Art (San Francisco-based, absurd, meaningless, ugly art)!

[Article on Edward Coley Burne-Jones as angel artist.]

The accurate and highly realistic landscapes of this generation influenced the plein air (open air painting) movement in Europe and US

Ultimately, the Pre-Raphaelite legacy turned into Symbolism, Naturalism, Art Nouveau, Art Deco. (Think Tiffany and the Art Deco buildings of Miami Beach!)

Here’s the link (20th-Century Art) if you want to see some of the other abstract art movements that litter our modern art galleries.

Downstream

A few years ago, a friend of mine took me to see Van Gogh’s famous “Starry Night” painting at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC, and while there, I also saw an art display that was literally a dirty t-shirt nailed to a wall.

In the next room was a soiled porcelain toilet littered with refuse all around that pretended to be art and several pictures of colored circles and squares that I was supposed to admire for their artistic genius. When art becomes a vehicle for pure self-expression, these types of displays are essentially what it devolves into.

However, when art conforms to objective standards of beauty (proportion, radiance, harmony, unity, etc.), it actually beautifies the world and brings beauty into the average person’s life.

Short-Lived but Powerful

The Pre-Raphaelite Movement was almost a flash in the pan as artistic movements go. The founding brotherhood lasted hardly five years before they broke up and went their separate ways.

Yet, they hit on something vital in art. They appealed to the human soul’s hunger for beauty and the inquiring intellect’s desire for truth. That is why the movement gave birth to a second generation, which increased and expanded their influence over time.

That second generation broadened and channeled their talents into numerous other movements and wide rivers of artistic beauty that endure to this day, especially the English Arts and Crafts movement which ended up affecting virtually every school child and adult in America.

In essence, the Arts and Crafts movement was a reaction to the rapid mechanization of human life of the Industrial Revolution in England. It emphasized a return to individual craftsmanship and an effort to bring exquisite workmanship into the homes of the average person. William Morris and his team brought very high standards of artistic beauty into the very heart of the home through practical artifacts created by very talented artists.

In America, “arts and crafts” is more of a child’s activity involving primitive attempts at creating pictures and rudimentary art forms. However, many of its precious relics of the Arts and Crafts movement may be seen on the Antiques Road Show today!

In any case, I hope you’ve enjoyed this excursion into the ravishing beauty that the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood brought into the world. We can thank God that art wasn’t left in the hands of the Surrealists.

What a wonderful article about the Pre-Raphaelites! The paintings you chose illuminate the exquisite work the Brotherhood brought to the world.

Thank you Donna, you are very kind. I have always loved these artists. They were a class act and left a beautiful legacy.