On a trip to New York City last year, I went with a friend to see the famed Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), where the striking Starry Night of Vincent Van Gogh is displayed. I had always wanted to see it firsthand and was not disappointed when I finally laid eyes on it.

But “disappointment” certainly describes my reaction to a number of the other MoMA displays erroneously described in the tour literature as art: the stained t-shirt tacked up on the wall; the toilet-drywall-wooden beam combo on the floor splattered with what looked like spray-painted leaves; the completely white square canvas (hanging next to the completely black square canvas), etc.

And don’t get me started on Jackson Pollock’s drippings (Google him if you need to).

What is behind this trend?

There is a single common phrase that justifies all modern art: “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” I confess to having used the phrase numerous times in my life.

On the surface, the observation seems accurate: what appeals to you may not appeal to me, and that’s okay. I find it hard to say that my taste might be better than yours. Individual preferences just can’t be compared. It is what it is, as they say.

Philosophically, the eye-of-the-beholder doctrine illustrates the principle of subjectivism (or value relativism) in aesthetics.

Subjectivism raises the phenomenon of personal preference to a kind of worship status that allows each of us to barricade ourselves in a fortress of personal opinion. Who can judge you if there is no objective measure by which we can compare preferences?

The main defect of the eye-of-the-beholder standard is that it is a closed system: if I happen to like something, it must, therefore, be good (I would not like something bad). And if I define something as good for me, then it must be my truth. And my truth, because it is mine, is undoubtedly a beautiful thing (I would never have an ugly truth).

Beauty, Truth and Goodness here are all rolled into one convenient, highly personal ethic that suits me very well and allows me to do whatever I want in my world.

As may be obvious, an ethic like this spells trouble for people who have to live together and find common ground in the real world. Value relativism is all I-me-mine, all the time. It isolates me in what is mine and will often put me at odds with others who insist on what is theirs, especially if the preferences conflict. On some matters we can’t both have our way.

Lacking a standard that all can judge objectively, subjectivism creates conflict.

Does subjectivism explain beauty?

After my visit to MoMa I began to wonder whether beauty really is in the eye of the beholder or whether there is a way to rise above that subjectivist conflict.

Why does Starry Night have a horde of picture-taking tourists in front of it, day-in and day-out, while people walk by the dirty t-shirt on the wall with hardly a glance? I must confess, I didn’t walk by that display without a glance. I stopped and gasped in horror that something so hideous could be featured in a world-famous museum.

When we were standing in front of Starry Night, I said to my friend: “It’s just us and sixty of our closest friends visiting Vincent today.” Most of those people were probably like me in that they paid the $25 entrance fee just to see that painting. Our visit turned out to be a communitarian experience in a way I hadn’t expected.

It’s clear that subjectivism, or mere personal preference, doesn’t explain beauty. We’re all allowed to have our opinions about what we consider beautiful, but the eye-of-the-beholder standard doesn’t explain why so many people agree on the beauty of the same things time and time again.

Pardon the pun, but there is much more to beauty than meets the eye.

The five qualities of beauty

Did you know there are five characteristics that make something beautiful? I didn’t either. But Fr. Thomas Dubay did, and he explained them in a wonderful book called, The Evidential Power of Beauty: Science and Theology Meet (Ignatius, 1999).

“Philosophical realism through the centuries,” notes Fr. Dubay, “has taught us that the beautiful is that which has unity, harmony, proportion, wholeness, and radiance.”

He then uses the analogy of the human face to describe how these qualities coordinate with one another other to make something beautiful:

The elements in a human face must be found together in oneness; otherwise ugliness has crept into the picture. There must be likewise harmony and proportion. Making this point, Plato offered the example of the unpleasantness we experience in seeing a body with one leg excessively long. A face in a painting becomes ugly should the artist decide to place an eye on the chin or cheek, or if you should have the nose and ear trade locales. Proportion therefore implies unity and wholeness. (171)

The larger point is that if something is unified, harmonious, proportionate, whole, and radiant, just about everyone recognizes its beauty, even if it may not necessarily be to an individual’s liking. Not everyone likes the Starry Night, of course, but even skeptics would not dare call it ugly.

A sharp contrast of styles

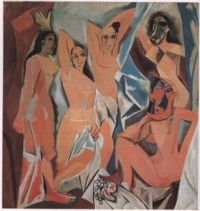

The idea of the dislocation of facial features may have reminded you, as it did me, of Pablo Picasso’s (1881-1973) works. Picasso was an artist of the early- to mid-20th century who is very difficult to label artistically as his style and interests changed significantly over his eight decades of painting.

Among other things, Picasso is called a cubist, a surrealist, an expressionist and a post-impressionist. Here, we are not attempting to analyze Picasso’s many styles or compare them to the more pleasing style of Van Gogh but to see if we can learn something about the five characteristics of beauty.

Picasso’s art is still avant garde in certain circles, but few people ever refer to his work as beautiful. Throughout most of his career, Picasso depicted the world as a sort of disjointed reality as did so many artists working in many disciplines during the early decades of the 20th century (Stravinsky, Joyce, Cummings, Graham, for example). They were reacting to the great cataclysm of World War I which left Europe (and therefore Western Civilization) broken an d in fragments.

d in fragments.

At MoMA, in an adjoining gallery to Starry Night, was one of Picasso’s most famous paintings, Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (see inserted image). This famous gathering of ladies of the night (created in 1907) was a social commentary on the fractured world of the already crumbling monarchies of Pre-World War I Europe.

One can say that the image accurately reflects a world that was corrupt, crumbling and uncertain; one is hard pressed to say that the image is beautiful.

If we were to apply the five-principle-test to Les Demoiselles, I believe the painting would fall short of an objective standard of beauty:

- Unity – although the scene holds together in one frame, it is shot through with broken shards of dull browns and blues, disjointed forms and minimalist images (fruit at bottom) that make it look more like a fractured window than a single, unified scene

- Harmony – the figures in the scene have no inherent order to their configuration; they are just thrown together and appear to look out menacingly at the viewer.

- Proportion – applying the facial standard of Fr. Dubay, most of the bodily features are angular or grotesquely disproportionate (note the eyes, noses, hands, arms and one large foot)

- Wholeness – the elements of this scene are not integrated into a larger whole; they are more like a collage of independent figures pasted onto a background; you could remove or replace any figure without having much of an impact on the whole scene

- Radiance – the figures are hardly recognizable as women let alone beautiful women; the colors are mostly sedate skin tones and bland, darker tones unevenly shaded. It certainly does not radiate with color.

A person who views this painting may admire it for its message: a cry of angst that erupted from a broken society. One may appreciate the unusual artistic imagination that created a group of courtesans with mask-like faces in seductive poses. But one can hardly stand in front of this painting and enter into its beauty in that way you can with Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

Fr. Dubay’s point is that these five qualities can be used as a standard to determine whether something is objectively beautiful, or not. They become a five-point measuring rod with which to compare the artistic merits of Van Goghs and Picassos.

[Let’s continue this discussion in Part 2 of this series. We’ll withhold the SOUL WORK section until the end of Part 3.]

Leave A Comment