What is a “codex”, you ask? Good question. In simplest terms, it’s a book.

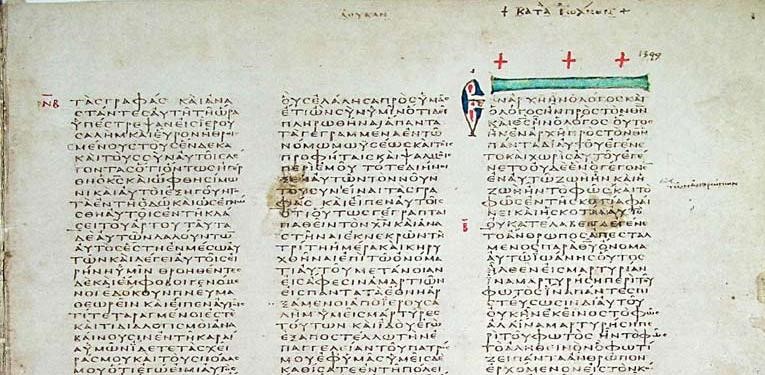

Hold on! That is true, but it doesn’t quite explain the full reality of an ancient codex, precisely when we’re talking about the famous Codex Sinaiticus, which has special significance for those of us who read the Bible. (When you read the word “Sinaiticus”, think Sinai, as in the desert of Sinai. We’ll explain further below.) The photo at the top of this post features a portion of a single page of this glorious book.

But let’s start at codex square one before we move on to the subject of the famous codex (plural, codices).

A cumbersome system

Mike and Grace Aquilina explained in their excellent work, A History of the Church in 100 Objects, that before codices came into existence, all written texts of the ancient world were found on scrolls.

We may remember from our school studies of ancient Egyptian culture that the material used to make scrolls was papyrus, a pulpy plant stem that could be hammered out and dried to make a writing surface. When many of these sheets were pasted together, they formed a very long bolt of material that sometimes stretched over 100 feet in length.

In fact, the longest scroll from ancient Egypt is 131 feet long! All ancient cultures with a literary heritage of one type or another produced scrolls of their sacred texts. Needless to say, Jesus read the Hebrew Scriptures from scrolls (Luke 4:16-21).

Such a long sheet had to be rolled up on both ends to make it usable and portable, which is why we call it a scroll. Our English word contains within itself the essence of its function: to roll. Other languages also reflect that rolling function (Spanish: rollo; Italian: ruotolo; French: rouleau).

Scrolls were generally written only on one side because a long roll of material was easier to read with the rollers face-up on either end. It was too difficult to turn a scroll over and use the rollers, which were then face-down, so they wrote only on one side. (One of my old bosses would say, “That’s a lot of wasted paper.” And it was!) There are some instances of two-sided scrolls, the most famous of which appears in the Book of Revelation (Revelation 5:1), but these were rare.

The greater difficulty of the papyrus scroll system, though, was in its lack of practicality. Imagine trying to find a reference to anything written in a scroll that is 100 feet long! It would take you forever. It was also hard to transport scrolls without damaging them. Even in ancient times it was a cumbersome system of storing written information, but it was all they had…until the codex came along.

Christianity’s role

The word codex originally meant “tree trunk” (Latin: caudex) because some early methods of writing consisted of wooden tablets coated with wax, on which students could write and erase. (Think of the slate tablets with erasable chalk used in the old schoolhouses of America and you have a modern equivalent of the clever method.)

The codex developed slowly throughout the ancient world until about the fourth century AD when it became a standard form of publishing. And Christianity had something to do with that.

Christians had Good News to give to the whole world and a divine mandate to share it. Many intelligent and zealous Christians began writing down the stories of Jesus (the Gospels) and sending letters to the early churches (St. Paul is the best example) so that the Christian testimony could be preserved. These writings began to be collected, read in church, carried to foreign lands, and passed on from one generation to the next.

For virtually all these activities, scrolls were too unwieldy. Papyrus was too fragile a material for constant use. It held up well in the dry environments of the Egyptian peninsula, but the wet climates of the Mediterranean needed something more durable.

The answer to these problems was parchment: namely, dried and stretched animal skins.

The invention of books

When some clever person got the idea of writing on dried animal skins, the technology of books was born: parchment and pages.

The benefits of animal skin were many. Skin was very easy to smooth out to create a writing surface without the defects or indentations papyrus had. Animal skin was durable. Best of all, a scribe could write on both sides of it without the ink bleeding through.

Skins were also easy to trim down into distinct pages, which were in turn easy to collect into groups of pages to produce – voilà – books!

Parchment and pages also made it possible for Christianity to produce the famous biblical codices, of which there are several: Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Alexandrinus. An ancient codex is known either by its place of origin (Sinai or Alexandria) or by its location (the Vatican).

In their most rudimentary form, early books were pages of parchment folded in half with their open leaves facing outward. Their folded edges were bound or sewn together with cord to make a spine. The books often had wooden covers locked together by clips, which helped preserve the tomes.

A Spanish publisher’s website offers a good description of many types of parchment publications if you wish to know more about this amazing technology that predated the printing press (1450).

Codex Sinaiticus

Today the word codex is synonymous with “collections” of materials. For example, the Catholic Church’s Codex Iuris Canonicis (Code of Canon Law) is a collection of all the particular laws that govern Catholic life. Secular and church law codices are the other ancient documents that have the greatest record of preservation after the scriptures.

In that sense, the Codex Sinaiticus is not a unique work written by one author, which is how we generally think of books today. It is a compilation of all the known writings that make up what we now call the Bible.

The names of those who compiled the Codex Sinaiticus are unknown to history, but it is almost certainly the work of three copyists/scribes (identified by their unique handwriting styles) who took the scattered versions of the biblical books available to them at the time and hand copied them to create one single book.

The whole manuscript is written in Greek and entirely in capital letters. There are no punctuation marks or chapter and paragraph divisions either. It would take another eight hundred years for the bible to be divided into chapters and a further three hundred for it to be divided into verses.

Production and date

The famous codex actually has its own website now (I’m sure the three original scribes would be pleased!) The site offers this description of the production process of the manuscript:

The ability to place these [biblical] books in a single codex itself influenced the way Christians thought about their books, and this is directly dependent upon the technological advances seen in Codex Sinaiticus. The quality of its parchment and the advanced binding structure that would have been needed to support over 730 large-format leaves, which make Codex Sinaiticus such an outstanding example of book manufacture, also made possible the concept of a “Bible”. The careful planning, skillful writing and editorial control needed for such an ambitious project gives us an invaluable insight into early Christian book production.

Clearly this is one of the most important books in history. Records date it back to the middle of the 4th century (350-400 AD). This fact indicates that it was produced after the Emperor Constantine liberated Christianity from persecution (313 AD), which then made it possible for the Gospel message to be spread throughout the Roman Empire. Having a complete set of scriptures to use for teaching and preaching gave great authority to the evangelizing efforts of missionaries, as it still does to this day.

St. Catherine Greek Orthodox Monastery, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt

A book divided

Here is another interesting description, from the website, concerning the current state of the Codex, 1700 years after its creation:

The Codex Sinaiticus is named after the Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, where it had been preserved until the middle of the nineteenth century. The principal surviving portion of the Codex, comprising 347 leaves, is now held by the British Library. A further 43 leaves are kept at the University Library in Leipzig. Parts of six leaves are held at the National Library of Russia in Saint Petersburg. Further portions remain at Saint Catherine’s Monastery.

It’s amazing to think that such a priceless treasure could exist in pieces, divided up among so many institutions. That sad reality is the result of the tumultuous history of Western and Middle Eastern civilizations since the mid-1800s. Prior to that, it was housed as a single volume in St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt.

We can’t go into the Codex’s amazing history here, but I encourage you to browse the website and read the many specifics of its history and composition when you have a minute. The website includes digitized pictures of every single page and fragment of the great book.

Composition

One final note: Codex Sinaticus contains a complete New Testament (27 books) and approximately half of the 46 books of the Old Testament. It also contains two additional ancient writings added as an appendix, which indicates that these two works (the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas) were venerated as holy writings but were not considered inspired works. They were not included in what the early church considered the text of the Bible. That is of great significance in that it shows the role of the Church itself in selecting the books to be included in the canon of scripture.

The other ancient biblical codex, the Codex Vaticanus, dates from the same era as Sinaiticus, although it is considered to be slightly older. It is the more complete scriptural codex of the two: it is missing several letters of St. Paul and the Book of Revelation in the New Testament but has retained virtually the entire Old Testament.

It is housed – you guessed it – at the Vatican!

One very important use

Of all the advantages of the codex as a new technology and as a means of communication in the ancient world, its “greatest benefit was that it accommodated use in the liturgy,” noted Mike and Grace Aquilina.

You could lay it down on a table or lectern, and it would stay flat. A preacher could move from passage to passage with little trouble. St. Justin Martyr recommends that the “memoirs of the apostles” were customarily read at mass in the city of Rome in 150. The codex made it possible to bind all four Gospels (hand written) between a single set of covers, and it seems that these were the first…collections of originally Christian Scriptures.

The Aquilinas go on to say that “the book as we know it – in the form of the codex – was born with Christianity. It was championed by Christianity…and it has Christianity to thank for its triumph and long endurance.”

Now, that is quite an accomplishment.

Clearly, the Codex Sinaiticus is not just any old codex. It is a priceless witness to many gifts that come to us from the Catholic Church’s sacred Tradition: information about the technology of books; insight into the life of the early church; confirmation of the unity of the Bible; and, above all, the proclamation of the Good News of Jesus Christ to the world!

Soul Work

Christians are identified by our love of Scripture, which we use as a guiding authority for our faith. The creation and preservation of the ancient codices are signs of the deep reverence we have for the Word of God.

It is important for us to read or listen to some portion of the scriptures every day, even if our reading takes only a few minutes. The Word of God is nourishment and healing for the soul.

Make sure that you not only own a personal Bible but that you also drink in its wisdom. Make the Word yours. It’s okay to make notations in your personal Bible as a means to memorize and strengthen your grasp of the written Word. Focus on your favorite books and passages of scripture and read them regularly.

Finally, make sure your Bible never gets covered up by clutter or lands on the floor. It should have a special prominence in your life, which means you should keep it in a special place. It is a divine work that must always be treated with great reverence – which is how the Church has embraced it from the beginning.

————

Source: Mike and Grace Aquilina, A History of the Church in 100 Objects (Notre Dame, Indiana: Ave Maria Press, 2017), 59-61. Photo Credit: Monastery, Berthold Werner via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave A Comment