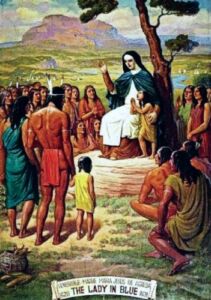

It’s a story that’s almost too incredible to believe, but a little-known Spanish nun who lived in the 1600s spent more than a decade visiting various tribes of Indians in New Mexico and Texas to teach them the Catholic Faith. These visits took place in the decade of the 1620s, but here’s the amazing thing: the nun never left Spain.

Venerable María of Ágreda (1602-1665) was a cloistered nun of the Order of the Immaculate Conception (in the Poor Clare / Franciscan tradition). As a contemplative nun, she was completely locked away from the world behind the massive walls of a convent.

Venerable María of Ágreda (1602-1665) was a cloistered nun of the Order of the Immaculate Conception (in the Poor Clare / Franciscan tradition). As a contemplative nun, she was completely locked away from the world behind the massive walls of a convent.

Transported by angels

Despite that, she was spiritually granted these visits to the Indians in North America during an eleven-year period. As she described it in one of her writings, she was “transported by the aid of angels” to evangelize the Jumanos Indians whose territory was centered close to what we now know as Albuquerque, NM. (At that time, the territory was called New Spain.)

She visited other tribes in North America at the time too, but the Jumanos seemed to be the focus of her major evangelization efforts. Why the Indians in the Southwestern region of our continent and not others? Only God really knows, but María testified later that He had revealed to her that these Indians had a special openness to grace. Isn’t that incredible?

This kind of paradox is typical of saints and saintly people: they combine in themselves things that appear contradictory and impossible: she was both in Spain and New Mexico at the same time; she was both a contemplative nun and an active evangelizer at the same time.

And did I mention that even though she was withdrawn from the affairs of men, the King of Spain consulted her for advice on many questions of state for over twenty years? God’s grace operating in the lives of saintly people like María of Ágreda makes these seeming contradictions possible.

The two great landings

If you know a little American history, you’ll realize that 1620 was the year the Pilgrims landed in America. María of Ágreda began visiting the Indians in the same year.

That was too much of a coincidence for one of the nun’s biographers, who wrote: “Of the two great landings in America in 1620 —the Pilgrims in the north at Plymouth and Agreda in the South— the mystical one has, and will yet have, far greater influence upon the history of the world.”

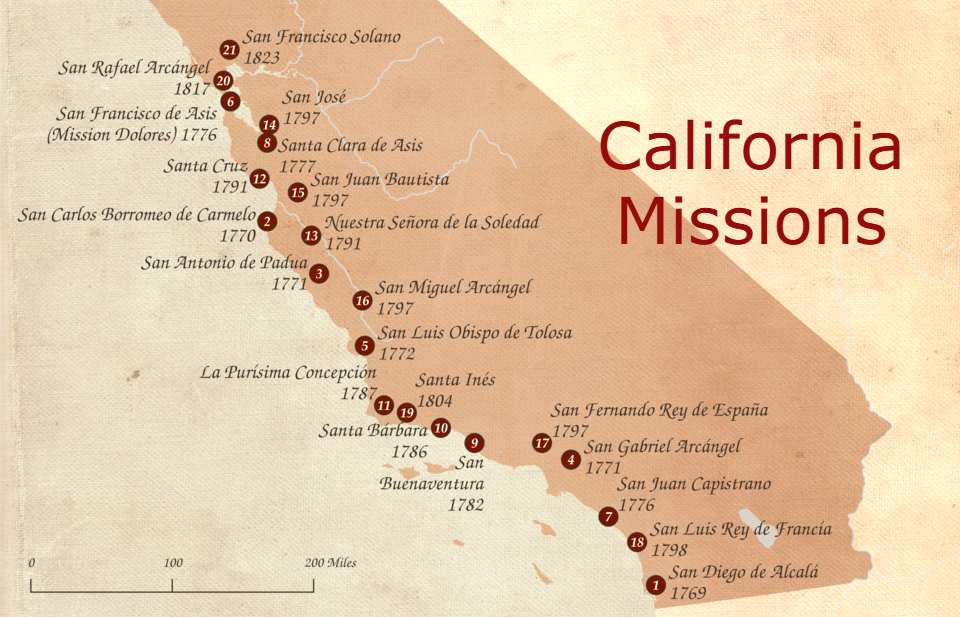

Her extraordinary visions became so famous among young Catholics of the era that they inspired many young men to become missionaries, particularly Franciscans, who were the primary evangelizers of the New World. There is a chain of Spanish missions dotting our southern and western states that stretches from St. Augustine in Florida all the way across the continent and up to San Francisco, California.

We’re all familiar with those incredible missions established by Junipero Serra (1713-84), but did you know that there were other Spanish missions in Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona as well? Here are just a few of them:

The Spanish had founded St. Augustine in 1565, which became the first permanent settlement in North America, so some Catholic missions predated her own mystical efforts. But the nun’s visions and bilocations can be considered the catalyst for the subsequent missionary efforts that occurred in the later 1600s and 1700s.

In fact, when Junipero Serra arrived in California (1767) to begin his missionary work more than 100 years after the nun had died, he wrote to another priest saying that “Agreda’s prophecy is about to be fulfilled in California.” Wow.

The lady in blue

Perhaps the most amazing part of this story is the way Sr. María of Ágreda was identified by the Church as the mystical woman who evangelized the indigenous peoples of the southwest. She didn’t advertise.

When her bilocations began, she disclosed the matter to her spiritual director to discern whether the mystical experiences were really from God. The spiritual director concluded that they were, and then wrote a letter to the Archbishop of Mexico City informing him of the nun’s request for baptism for the Indians.

(Right: María of Ágreda’s convent today, largely unchanged since the 1600s.)

The Archbishop, in turn, sent word to Franciscan Fr. Alonso de Benavides, superior of the closest mission station, ordering him to dispatch missionaries to the area to verify if this was true. Fr. Benavides in fact already knew of the request because a group of Indians had walked hundreds of miles to the station asking for priests to come and baptize the whole tribe.

When asked who told them about the Christian faith, they responded that it was “the lady in blue” as they called her. They did not know her name, but they knew the cloak she wore, which corresponded the religious habit of Ágreda’s order.

Fr. Benavides’ missionaries baptized thousands of Indians in that visit alone, including other indigenous tribes who showed up when they heard the missionaries were there. When they asked these other tribes who told them that they should seek baptism, they replied similarly: “The lady in blue.”

Eight years of searching

The mystical revelation was thus confirmed, but the mysterious woman’s identity was still unknown. Actually, the Archbishop knew it but for some strange reason did not disclose it to Fr. Benavides, who he must have thought had the gift of reading prelates’ minds. Seems like an important piece of information.

But rather than go back to the Archbishop and ask, “Who is this incredible woman?!” Benavides chose, instead, to trek around Spain telling the story and asking if anyone knew who she was. What was he thinking? Anyway, after eight years, he happened to bump into the nun’s spiritual director at a convent in Madrid, and the priest informed him of the mystic nun’s identity.

But rather than go back to the Archbishop and ask, “Who is this incredible woman?!” Benavides chose, instead, to trek around Spain telling the story and asking if anyone knew who she was. What was he thinking? Anyway, after eight years, he happened to bump into the nun’s spiritual director at a convent in Madrid, and the priest informed him of the mystic nun’s identity.

The Spanish missionaries were courageous men, I’ll give them that, but even with the slow communications of the day, did they really need eight years to sort it out?!

Benavides proceeded to personally interview the nun, who, under religious obedience, admitted to the extraordinary experiences and disclosed to him highly pertinent and specific details about the Indians that only a missionary like Benavides would have been able to corroborate. She also identified the specific missionaries who had baptized the Indians—and claimed that she had been there watching!

When the Franciscan returned to the mission territory he brought a small painting of the nun and asked the Indians if they knew her. They immediately recognized the blue cloak but said the woman who visited them had looked younger. Indeed, she must have been in a kind of transformed mystic state and appeared to them younger than she was.

The other thing that amazed the Indians was that this lady in blue was often persecuted for spreading the Christian Faith. She was captured and even tortured and left for dead by hostile Indian tribes. Yet, she kept coming back to the Jumanos in her same pristine form each time. In the course of the decade, she claimed to have visited the Indians of New Mexico over 500 times.

Mystical writings

Mystical writings

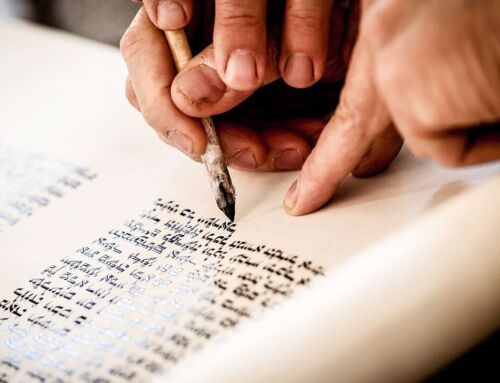

When María of Ágreda wasn’t bilocating to America, the humble nun became Mother Superior of her small community and also wrote at least 14 mystical treatises, some of which have never been published. These were not theological works, as such, but accounts of the mystical visions she had been granted during her entire life. She claims to have been receiving mystical experiences from the age of four.

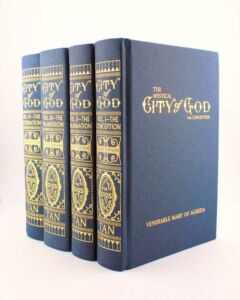

Her most famous work was/is The Mystical City of God, which runs to 2,676 pages! It is still in print today in a four-volume set or in a condensed form that is only a couple hundred pages. (On sale at TAN Books now.)

The full treatise goes into detail about the creation, the Fall of the angels, and the whole history of salvation. The abridged version focuses on the events surrounding the life of Our Lady and the hidden life of Holy Family as well as details of the public ministry and Passion of Our Lord. I have found the smaller book to be utterly fascinating.

The full treatise goes into detail about the creation, the Fall of the angels, and the whole history of salvation. The abridged version focuses on the events surrounding the life of Our Lady and the hidden life of Holy Family as well as details of the public ministry and Passion of Our Lord. I have found the smaller book to be utterly fascinating.

Persecution

But, of course, what would a good, heroic Church story be like without a bit of persecution to spice it up? Under the rubric of “no good deed goes unpunished,” she was also persecuted for her writings, which, admittedly, were unusual for her day in both style and substance.

If you ever want to make a priest or bishop nervous, tell him you’re having visions. At first he’ll ignore you, then if you persist, he’ll get alarmed and investigate you or send some priests to “verify” your status (as happened in Mexico)—and then when all else fails, he’ll sic the Spanish Inquisition on you!

Which is exactly what happened to poor Sister María.

Official Seal of the Spanish Inquisition

Ironically, the Spanish Inquisition of the day actually cleared The Mystical City of God of any theological error, but the cause was kicked over to Rome where the work was condemned in 1681. Then it was translated into French and condemned again by a commission of the University of Paris in 1696. To rub salt in the wound, the work was then placed on the Index of Forbidden Books.

All of these issues were eventually resolved after her death. Like the Divine Mercy apparitions in the 20th century, officials later determined that the misunderstandings came from bad translations, and her works were eventually freed up for wider distribution. In fact, now, all her works that have been published carry the Imprimatur from local bishops. An amazing turn around, I’d say.

It’s tempting to try to summarize some of her visions here for you, but I’ll have to leave that to another article because they are extraordinary and beautiful and described in abundant detail that defies simplification.

Sainthood process

You’d think that someone as mystical and saintly as “the lady in blue” would be a prime candidate for canonization, but the taint of the Inquisition fiasco has hung  over her head for centuries. Yet, because of her confirmed life of holiness María of Ágreda was declared “Venerable” (at that time the first step in the canonization process, before beatification) in 1675, just ten years after her death. Maybe in time her cause will go past that first step.

over her head for centuries. Yet, because of her confirmed life of holiness María of Ágreda was declared “Venerable” (at that time the first step in the canonization process, before beatification) in 1675, just ten years after her death. Maybe in time her cause will go past that first step.

In another paradox, she is also one of those “incorruptible” saints whose body has remained unaffected by the decay of death. Authorities opened her casket both in 1909 and in 1991 and found her in a perfect state of preservation.

So, whether she ever becomes a canonized saint or not, we are privileged both by her incredible evangelizing visits to the Indians of our land as well as her writings that increase the gift of faith in us to this day. In her own way, María of Ágreda is a sacred window of grace and zeal for us to look through to get a brief glimpse of that wonderful Mystical City of God.

———-

Feature Image: Mission San José de Tumacácori (Larry Lamsa. Courtesy of Flickr_Credit: AZ Skies); Portrait (Public domain); Texas missions (Texas Almanac); NM Missions (Mexico Nomad); California missions (Shruti Mukhtyar); Visions (Mexican School); Convent (Zarateman); Spanish Inquisition Seal (Di); Agreda Preaching to the Native Americans (Michael Journal); Tomb (Zarateman).

Leave A Comment