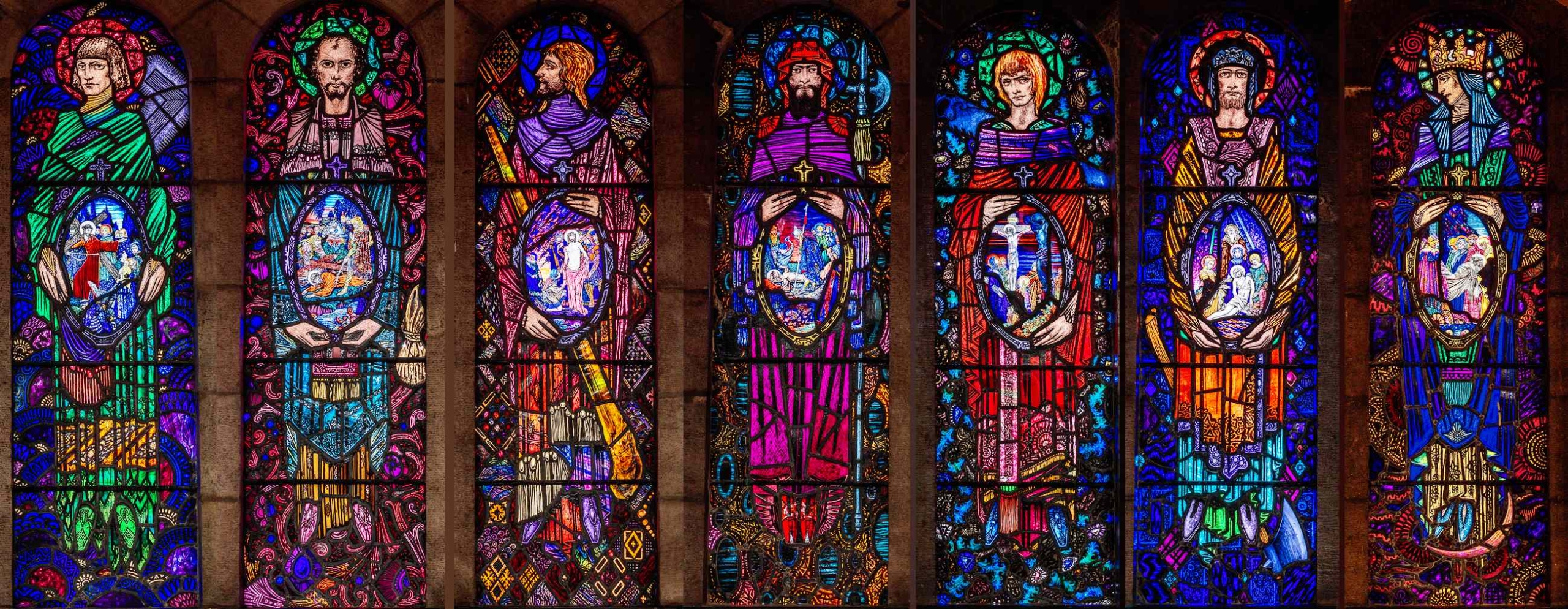

The stained glass Stations of the Cross created by the artistic genius, Harry Clarke, are so beautiful that when I look at them I find it hard to get into the penitential spirit of Lent!

But radiant beauty and self-denial are not mutually exclusive in the authentically Catholic view of things. In a sense, the formula is the reverse. Self-denial is really the pathway to experiencing true beauty. When we overcome selfish pursuits by practices like prayer, almsgiving, and fasting, we open our hearts to a higher Life and make them more receptive to an ancient Beauty that cannot be perceived on the surface of life.

In other words, Lenten penances are not the sacred windows of God’s grace; they are the forces that open the windows of our hearts to let the Light in.

And speaking of ancient, the place where you will find Harry Clarke’s lovely stained glass windows is an island in the middle of a lake in northwestern Ireland that has been a place of Christian pilgrimage since the time of St. Patrick (ca. 432-493 AD) himself.

Anyone can do the math; specifically, people have been journeying to that island for over FIFTEEN. HUNDRED. YEARS.I’ll show you the windows in a minute, but first a note about the pilgrimage center.

The Pedigree

It is called Lough (pron. “lock”) Derg, and it consists of one main island and a few other tiny islands in the middle of a lake in Country Donegal, Ireland (about 130 miles northwest of Dublin). Its spiritual heart is the island called St. Patrick’s Purgatory, which should tell you all you need to know about its austerity.

Early information about the island is scarce, so we have to rely on oral tradition and ancient legends for information about the place.

Early information about the island is scarce, so we have to rely on oral tradition and ancient legends for information about the place.

The first legend is that the place got its name, Derg (which means “red” in Irish Gaelic) from something that St. Patrick did while he was there. It is said that a huge serpent inhabited the place, and Patrick slew it to remove the danger but also to symbolize the victory of Christ over the devil.

The shed blood of the serpent gave the place its name. (Judging from the other tradition that Patrick drove all the snakes out of Ireland, apparently, he was pretty inimical to snakes.)

A second legend has it that the great Apostle of Ireland visited the island in a moment of deep discouragement when the native people were resistant to the message he was preaching. It is said that Jesus directed Patrick to a large pit or cave on the island and told the missionary that the people would believe his words if they spent a day and night in there.

Early legends indicate that people who went down into the cave overnight experienced both the blessedness of heaven and the rigors of the damned, which was convincing enough for the people to begin to believe Patrick’s teaching about salvation.

Early legends indicate that people who went down into the cave overnight experienced both the blessedness of heaven and the rigors of the damned, which was convincing enough for the people to begin to believe Patrick’s teaching about salvation.

Anyway, killing snakes as a sign of victory over the devil; using a cave to teach about Heaven and Hell; and instructing the people about the Holy Trinity with the three-leaf Shamrock – I’d say St. Patrick was a master communicator and evangelist.

“The twentieth century blows across it now / but deeply it has kept an ancient vow.” – Patrick Kavanagh, Irish poet

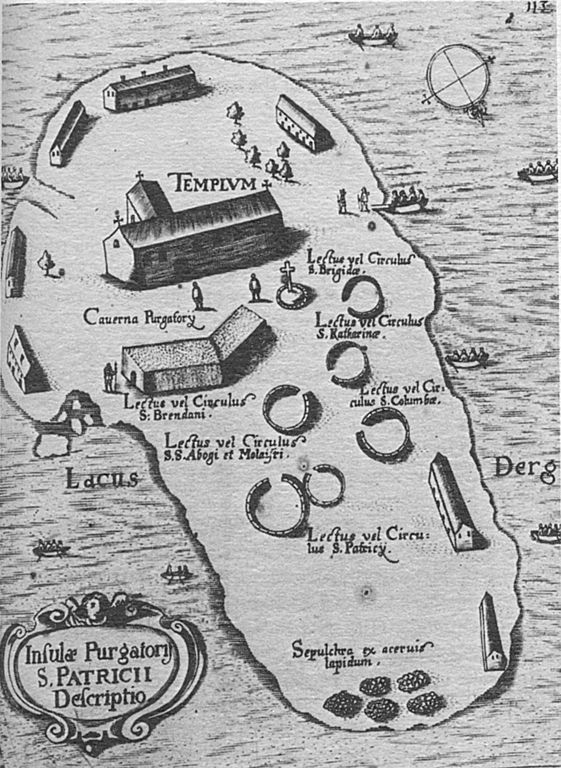

1666 map of the island

Same island today (called Station Island)

The Regimen

Like all things devotional, St. Patrick’s Purgatory flourished during the Middle Ages, and to this day it is a place of annual pilgrimage during the summer months. Documents indicate that a wide array of sinners and criminals would come from all over Europe during the months of June through August 15th to make penitential pilgrimages to expiate their sins.

Here is one account of what took place when they came:

Documents report that pilgrims who did want to visit the Purgatory would arrive with letters of permission from a bishop, either from their own region or from Armagh. They would then spend fifteen days fasting and praying to prepare themselves for the visit to Station Island, a short boat ride away.

At the end of the fifteen days, pilgrims would confess their sins, receive communion and undergo a few final rituals before being locked in the cave for twenty-four hours. The next morning the prior would open the door, and if the pilgrim were found alive, he would be brought back to Saints Island for another fifteen days of prayer and fasting. (Source.)

[NOTE TO SELF: if anyone ever offers to take you in a time machine back to Medieval Ireland to make a pilgrimage… maybe decline the offer?]

Today, the regimen is a bit truncated from its medieval rigor, though not by much. The duration is shorter – the pilgrimage lasts only three days – but you must begin fasting even before you arrive. Then they ferry you to Station Island where you spend the first night in prayer in the island’s church. You can sleep the second night.

You remain barefoot the whole three days, and they let you eat one meal of dry toast, oatcakes, and tea or coffee each day. (They reluctantly added coffee to the menu only in the Year of Our Lord 1983!)

You remain barefoot the whole three days, and they let you eat one meal of dry toast, oatcakes, and tea or coffee each day. (They reluctantly added coffee to the menu only in the Year of Our Lord 1983!)

A continuous cycle of prayer and liturgies keeps you occupied for the time you are there, and on the third day you are ferried back to the main island where you must remain in prayer and fasting until midnight of that last day. While the number fluctuates from year to year, about 10,000 pilgrims a year, mostly from Ireland itself, go through that three-day ordeal at St. Patrick’s Purgatory. Wow.

(And just to remind you that we live in the modern Internet age, these days you can book your three-day ordeal online!) Now, let’s get a look at those windows.

The Magnificent Stations of the Cross

First of all, I’d like to thank the Very Rev. Laurence J. La Flynn, Prior of Lough Derg, for permission to use the stained glass images (below) as well as the gracious help of Maureen Boyle for her assistance in forwarding them to me.

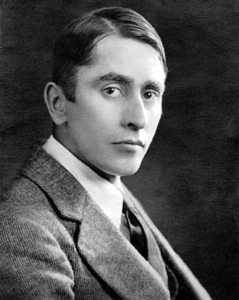

The windows are the creations of Harry Clarke (1889-1931), who is Ireland’s preeminent stained glass artist. It will only take one look at his work to see why. He was amazingly prolific and talented, creating some 160 exquisite stained glass windows prior to his untimely death at the age of only 41.

The windows are the creations of Harry Clarke (1889-1931), who is Ireland’s preeminent stained glass artist. It will only take one look at his work to see why. He was amazingly prolific and talented, creating some 160 exquisite stained glass windows prior to his untimely death at the age of only 41.

His work, primarily done in the 1920s, cannot be exactly classified, but it is generally considered to be in the genre of the Art Deco or Art Nouveau movements, although he was also highly influenced by the medieval stained glass of Chartres Cathedral and the work of many Renaissance painters.

I’ve written about his life and work in “The Greatest Stained Glass Artist You’ve Never Heard Of”, but rather than rehash the details here, I’ll just direct you to that page where you can see a sampling of his unbelievable work.

Like all artists, however, Clarke has to be seen in context. Irish independence in 1921 led to a flourishing of Irish art, architecture, and a whole host of cultural renewal projects, and, lucky for Ireland, Harry Clarke came of age as a man and an artist just at that time. When a priest friend of his decided to build a new church on Lough Derg in 1925, Clarke got the commission for fourteen stained glass Stations of the Cross for the new church.

He began the project in 1927 and finished in 1929 when the windows were consecrated. The church, unsurprisingly named St. Patrick’s Basilica, was completed in 1931.

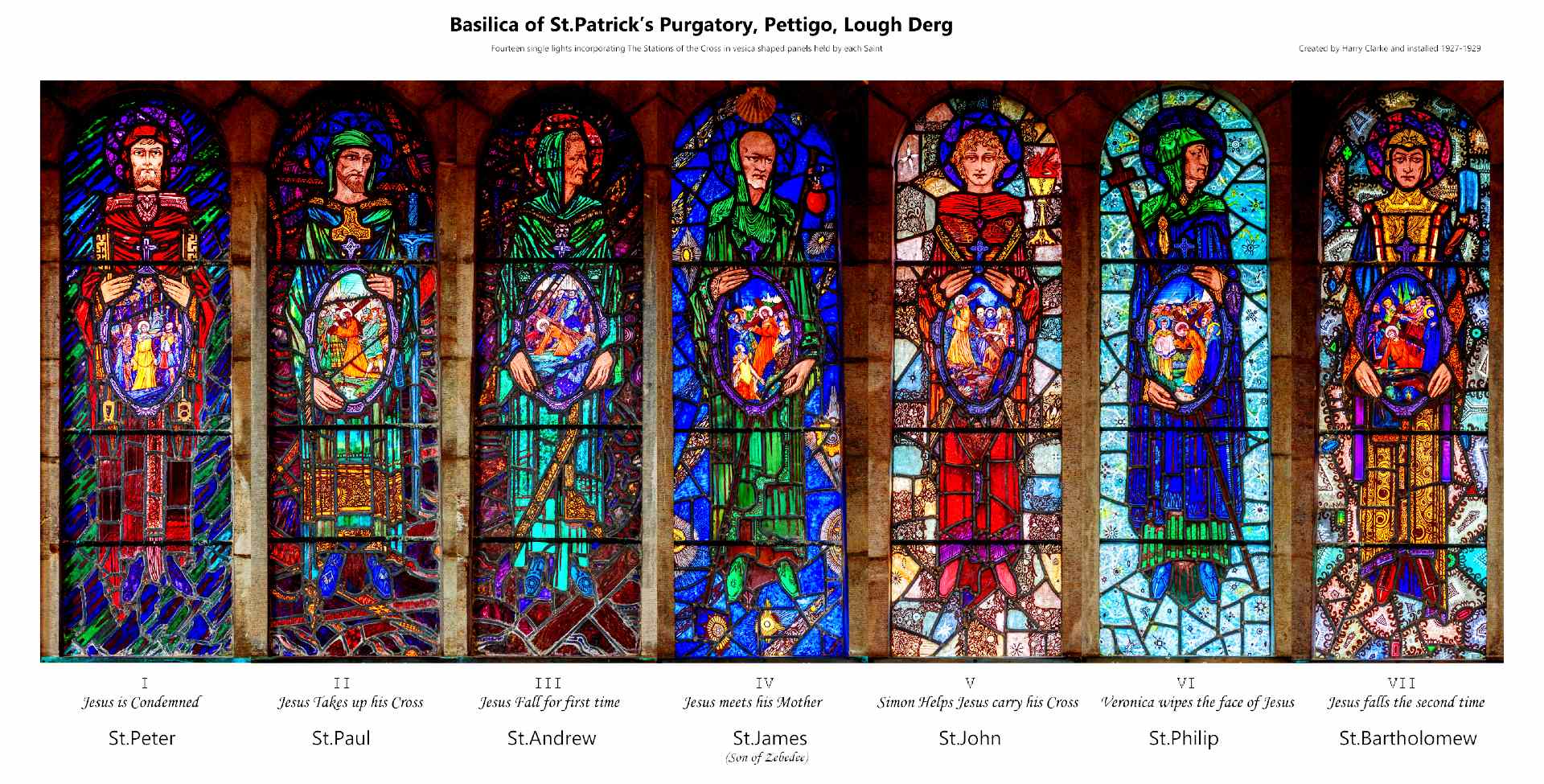

As with all Stations of the Cross, there are fourteen Stations, and in this case they are windows rather than the usual sculptures or paintings. The fourteen consist of twelve apostles plus St. Paul and the Virgin Mary, each holding an inset oval panel of the particular Station.

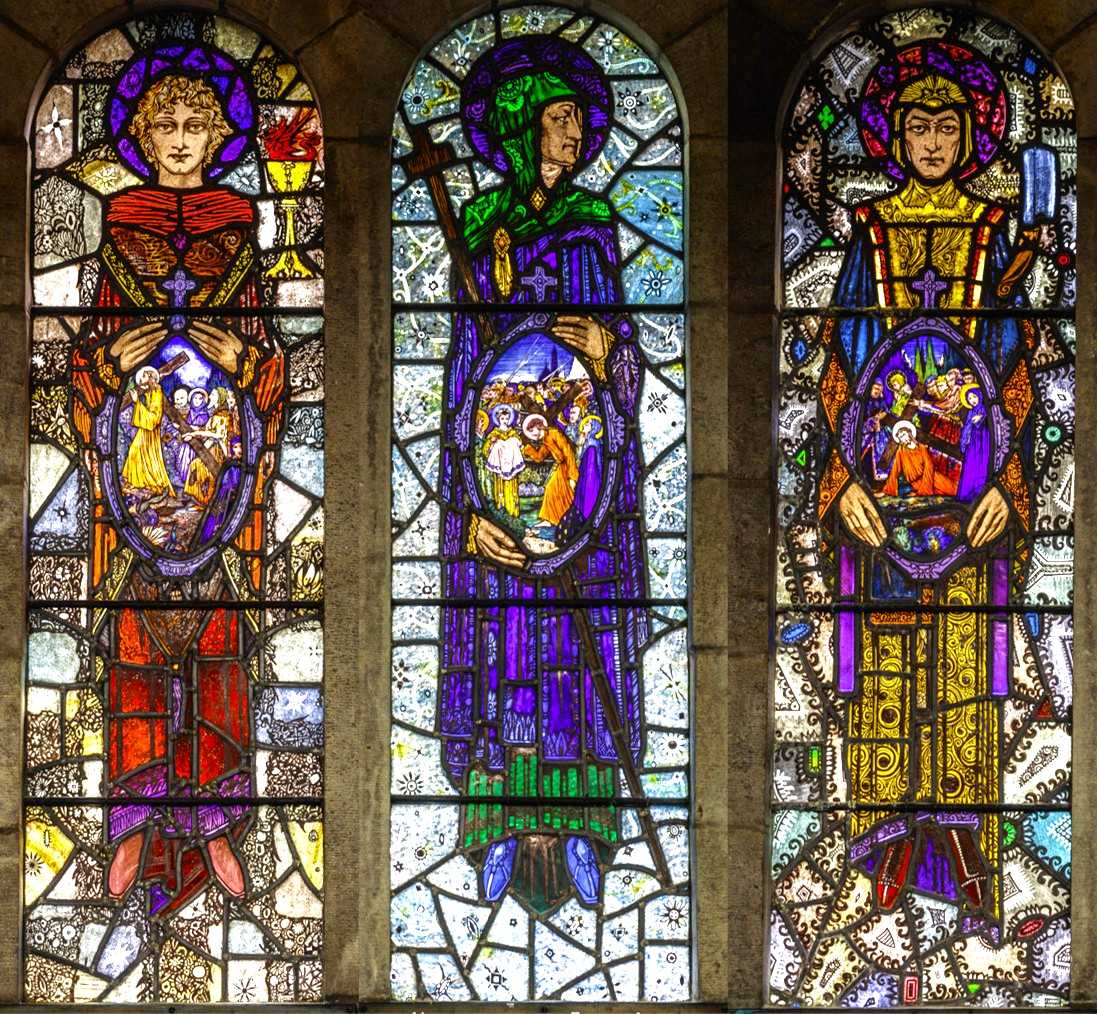

Below you’ll see three more saints excerpted from the full panels as well as one single window of the First Station, just to whet your appetite for a close-up look of them all.

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to include all of them in this newsletter, but I’ve displayed every one of them on the Sacred Windows website for you to feast your eyes on when you have a minute. Just click the button, and you’ll be taken to that web page to see all the glorious details.

What to Look For

In these windows and all the others, pay attention to the following:

- Brilliant colors! (Imagine what they look like with sunlight shining through them.)

- Each apostle bears a traditional symbol of his martyrdom or his office, while the Virgin Mary (last Station) wears a crown.

- The image of St. Peter features him with the Keys of the Kingdom above his hands, a bright purple halo, and a splash of diagonal rays of blue and green behind him.

- Note that there is not a single repetition of shape, background pattern, color scheme, halo style, etc. among all the images.

- The image in each inset oval looks more like a Renaissance painting than a stained Glass window, but every inch of the work is in glass.

St. John (Station 5) | St. Philip (Station 6) | St. Bartholomew (Station 7)

St. Simon (Station 12) | St. Matthias (Station 13) | Virgin Mary (Station 14)

St. Simon (Station 12) | St. Matthias (Station 13) | Virgin Mary (Station 14)

St. Simon (Station 12) | St. Matthias (Station 13) | Virgin Mary (Station 14)

An Obscure Treasure

So, if these stained glass windows are literally the best in the world, how is it possible that so few people know about them?

Well, there’s a very simple answer to that question. It’s probably because you have to spend three days cut off from civilization and do a good bit of penance for your sins just to lay eyes on their radiant beauty.

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 3/19/23, so it does not end with the regular Soul Work section. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Stained Glass Credits: Harry Clarke stained glass windows – Lough Derg, Pettigo, Co. Donegal; James Edwards, photographer. Photo Credits via Wikimedia Commons: 1666 Map (Thomas Carve, Public domain); St. Patrick (Nheyob, CC BY-SA 4.0); Harry Clarke (Public domain); Saint Patrick’s Purgatory Entrance (Kenneth Allen); Modern-day Station Island (loughderg.org).

Leave A Comment