The Book of Genesis tells us that we are made in the image and likeness of God, which means we are creatures who are literally made to worship the One in whose image we are made.

Surely, animals worship God in their own way, but humans are able to worship God “in spirit and in truth” (Jn 4:24). We have a spiritual soul for that very reason.

Spiritual dampeners

But it’s also true that the spirit of worship can be easily stamped out. All types of sin dull our spirits for worship as also worldliness and the power of evil (the traditional enemies of our souls: the world, the flesh, and the devil.)

Something else also dampens the human spirit and the innate desire to worship God: i.e., bad liturgy—usually accompanied by awful church architecture. I’ll illustrate what I mean.

I once walked into a Catholic church which was almost completely empty of any religious art. The back wall behind the modernistic altar was a sheer, blank barrage of flat, gray rock with a huge statue of a non-crucified Christ hanging on it. I would have been horrified had I not already been familiar with many of these types of new-fangled churches.

(The above picture is not the same church I saw, but it’s pretty close!) I was with a priest at the time, and when I asked him why the church was so barren, he told me that the architect thought that the people who filled up the “worship space” when they came to Mass…were the decorations.

I came to the conclusion that the architect’s theology was almost as bad as his architecture.

People are not objects and decorations, even for worship. They are human subjects who do the worshipping! The architect must have missed that lecture in architecture school.

The heart looks upward

When you experience bad liturgy, it’s inevitably flat. It seems more a stage production than an occasion of worship, horizontal and human-centered, rather than vertical and God-oriented, as it should be.

That’s because liturgy is divine worship, and worship is not meant to be a stage. It’s meant to be a launching pad. It’s supposed to direct our hearts and minds to God and lift our souls heavenward.

When the psalmist wrote of his profound religious experience in nature, he did not say, “Gosh, that flat, wide open empty plain was such a mystical place.”

Rather, he marveled at the verticality of his experience:

Rather, he marveled at the verticality of his experience:

“I lift up my eyes to the mountains, whence comes my help? My help comes from the Lord who made heaven and earth!” (Psalm 121:1-2)

The psalmist also prayed:

“Let my prayer rise like incense before you, may the lifting up of my hands be like the evening sacrifice.” (Psalm 141:2).

The angels in the Book of Revelation echo this religious sentiment as they join us in offering worship and prayer in one vast upward movement:

“The smoke of the incense along with the prayers of the holy ones went up before God from the hand of the angel.” (Rev 8:4)

The point is very simple: the direction of all authentic worship is upward. It is not because God is physically up above us (He is literally everywhere) but because the lifting up of our eyes and hands symbolizes the lifting up of our whole beings in worship.

And I probably don’t need to tell you what the polar opposite—“downward”—symbolizes.

Heaven participates

Why is all this important? Well, because we are by nature earth-bound. Good liturgy, art, and architecture help to lift our hearts to God in prayer and reverence.

And we’re not the only ones who experience that: St. John Chrysostom said that “when the Eucharist is being celebrated, the sanctuary is filled with countless angels who adore the divine victim immolated on the altar.”

St. Augustine reiterated that same theological sentiment: “The angels surround and help the priest when he is celebrating Mass.”

In other words, the inhabitants of the invisible world above us literally bend down to us when we are in worship at Mass. They exist in the realm of blessedness and assist us in getting there too.

The reredos reality

So, nothing creates the conditions for this heavenly encounter better than good liturgy and exquisite architecture.

I could talk at length about forms of architecture that inspire devotion (like my favorite, Gothic), but I will limit myself here to one aspect of church architecture that makes you feel as if all of heaven were present with you in worship: the reredos.

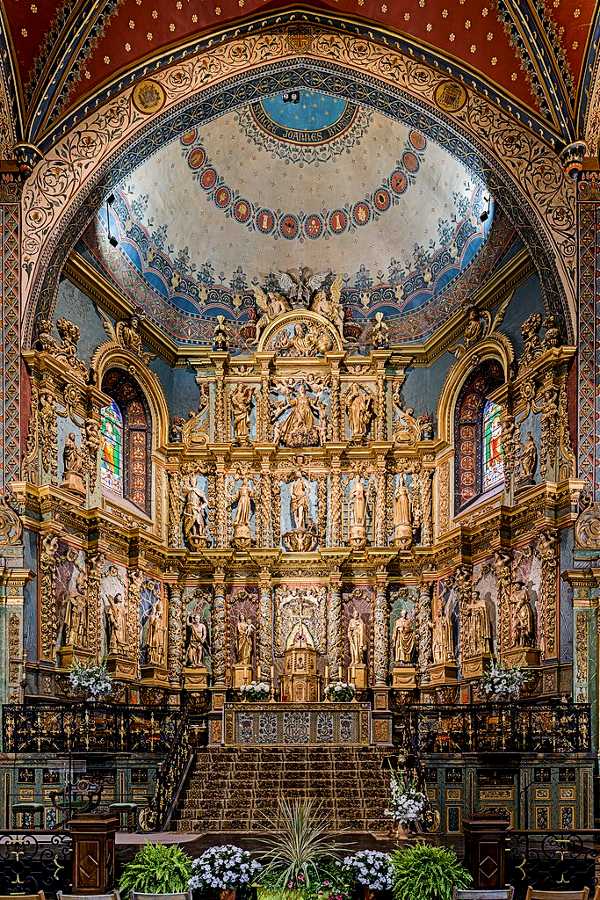

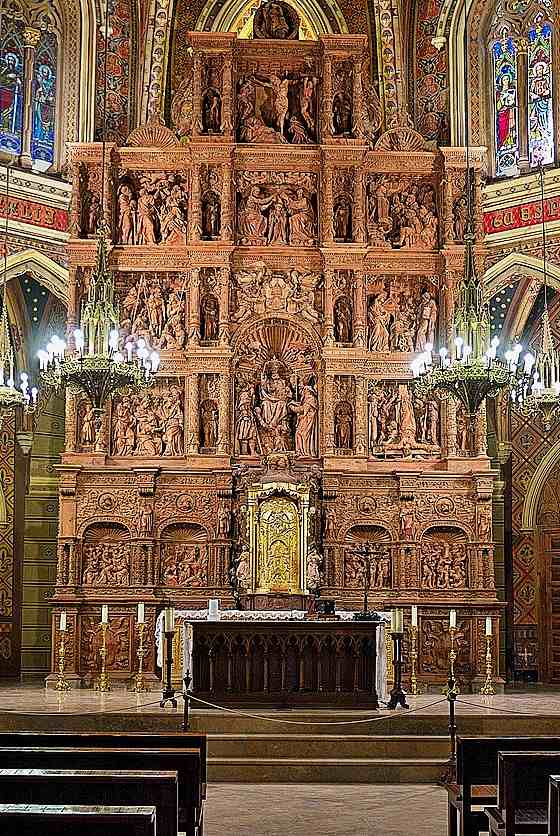

What in the world is that? Well, it’s easier to show it first and then describe it. Here are two stunning examples of what we call a reredos.

Pretty impressive, right? (Notice the size of the people on the left.)

The name “reredos” comes from the Middle English word “arere” which simply means “behind”—our English term, “to be in arrears” derives from this word. To it is added the Latin abbreviation “dos” which comes from “dorsum” (back).

That’s a complicated way of saying that a reredos is a decorative wall that rises up behind an altar!

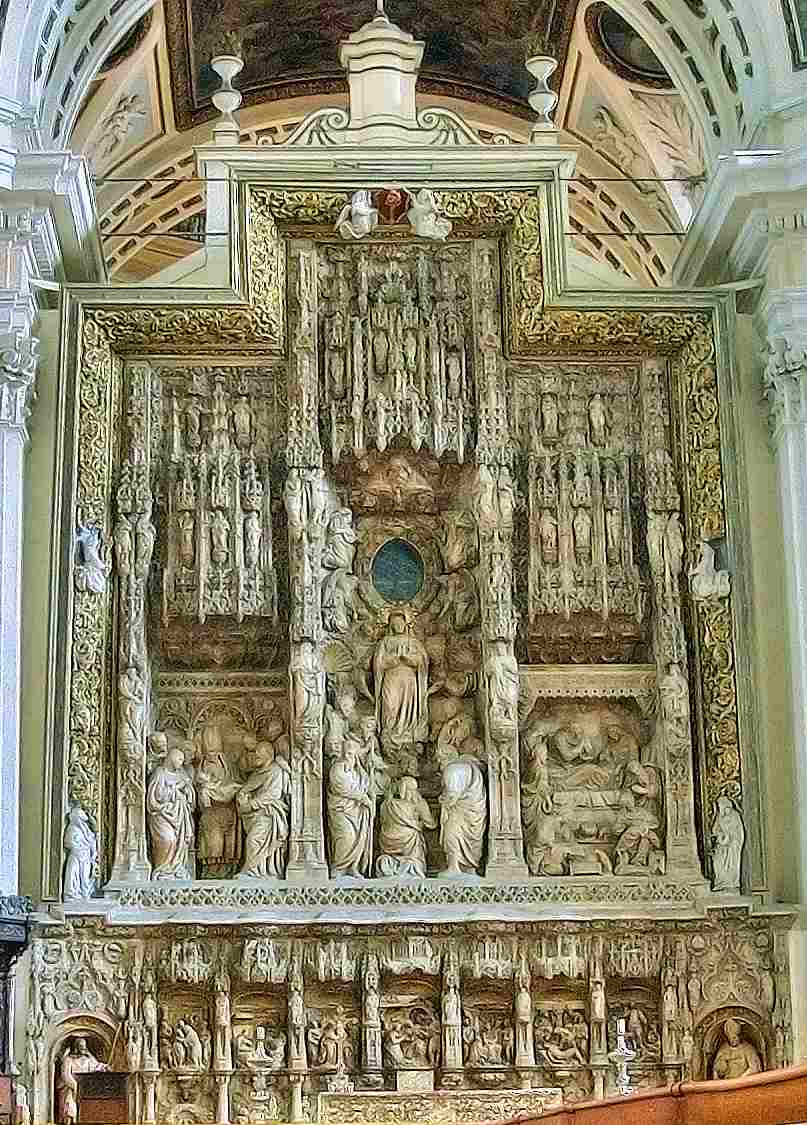

We distinguish a reredos from a retable or an altarpiece, which are works of art or panels that are attached to the back of an altar, not the wall as such. These often get lumped into the general term reredos, but here, we are just focusing on those amazing back walls.

Characteristics

As you’ll notice in the two examples above, the entire back wall of the sanctuary is filled with statues of saints and angels.

Remember what I said about “heaven bending down”? This is how previous generations of church builders envisioned heaven’s participation in the divine liturgy of the Mass. Awesome!

A few more interesting details about reredoses:

- They often (but not always) fill the entire back wall of a church from floor to ceiling and form what can largely be described as a sort of “sacred window” whereby the citizens of heaven peer into the church from on high and join with the citizens of the earthly church in worship;

- A full reredos wall rarely appears in churches that have domes over the sanctuary because they would obscure the artwork of the dome. (You’ll see two exceptions below which look like the dome is incorporated into the art.)

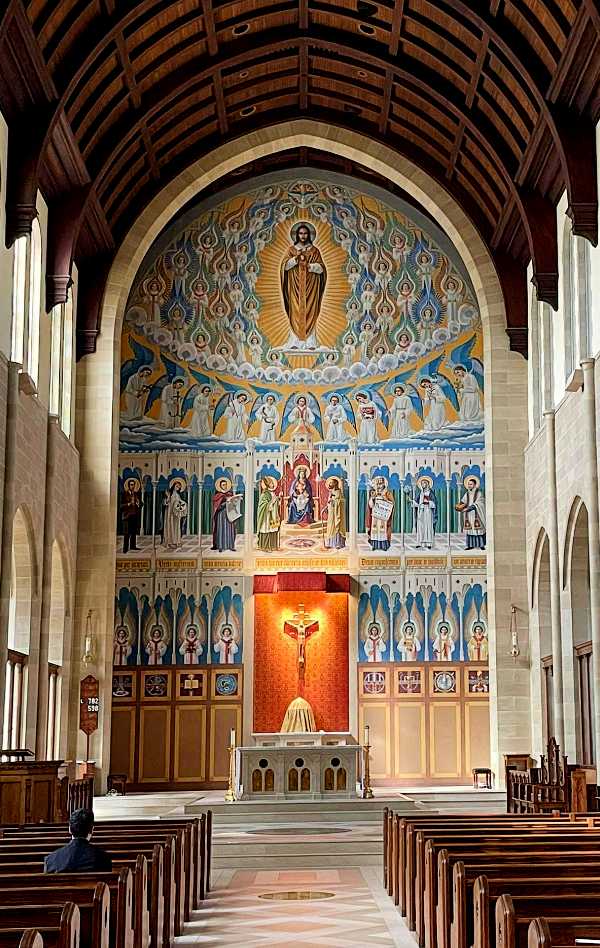

- A reredos usually consists of carved statues in niches or wood carved frames for religious paintings, but entire walls can be painted with religious art, such as you’ll see in the image of the Josephinum Seminary below. It’s magnificent.

- Some reredoses combine both statuary and paintings to form a unique backdrop to the altar, which leads us to the final insight:

Post-Vatican II churches are almost never built with a reredos because the altars are free-standing. It is most perfectly the backdrop of an altar for the Traditional Latin Mass, where the priest faces east with the people in worship and looks up to heaven whose inhabitants come to offer worship with the people.

As we saw in the biblical quotes above, the saints and angels assist in offering our prayers “like incense” up to heaven.

A feast for the eyes and the soul

The magnificent architectural tradition of the reredos transfixes the human heart, which is made for worship.

All worship is “in spirit and truth”, so a person can worship God in a forest, on a plain, or in a dungeon if he has maturity of soul. But man best worships when he has tangible reminders that direct his heart, his mind, his eyes, and his soul…upward.

Let’s end with a gallery of stunning reredoses, from various different nations, just to show that this worship tradition is universal. I searched through hundreds of pictures to find those that I considered to be the most magnificent, but trust me, this whole subject is a feast of riches.

A curious reredos inhabitant

Oh, and by the way. If you go to St. Thomas Episcopal Church in New York (the very first reredos pictured at the top of this article), you will drink in the magnificence of that wonderful reredos. (The rose window at the back of that church is equally stunning.)

Oh, and by the way. If you go to St. Thomas Episcopal Church in New York (the very first reredos pictured at the top of this article), you will drink in the magnificence of that wonderful reredos. (The rose window at the back of that church is equally stunning.)

There is one anomaly in the church, however. They put George Washington’s statue at the edge of the reredos! (Top right, second statue down.)

Washington is not a canonized saint even for the Episcopalians, but I imagine that Old George looking down on you in church does make for an interesting—ahem—“worship experience.”

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 10/01/23, so it does not end with the regular Soul Work section. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Photo Credits: Modernist church; thurible and incense via Pixabay; St. Thomas Episcopal and George Washington via Peter Darcy; Wikimedia licenses: CC BY-SA 3.0 and CC BY-SA 4.0; (Oxford College Chapel) MykReeve; (Detail 1, Oxford) Stefan Schwarz; (Detail 2, Tarançon) Zarateman, CC0; (Burgos) José Luis Filpo Cabana; (Avila) José Luis Filpo Cabana; (Saint-Jean-de-Luz) Benh LIEU SONG (Flickr), (Rouen) Tango7174; (Santa Fe) Chris Light; (Josephinum) Thom Price Facebook Page; (Capistrano) Mark Steven Brown; (Ibaan) Judgefloro; (Cebu City) LMP 2001.

I once read that George Washington, who was very friendly with a Catholic priest, called for him at the hour of his death. The priest would not reveal what took place but was reportedly very pleased to be with him at the hour of his death. It seems obvious to me what happened. He must have requested the priest keep it a secret. That is humility at its finest. Amen. +