I really don’t remember how many years ago it was that I bought a tiny anthology of Robert Frost poems. It was one in a series called Great American Poets. A small book of twenty-three poems, just sixty pages long with a hard cover and dust jacket. It’s hardly larger than most cell phones today but with much more valuable content.

Except for the Bible, it has to be the most read book in my library. To this day, the little volume sits on my bookshelf about eighteen inches from my shoulder as I write, always ready at hand. I pick it up when I need a burst of inspiration or a metaphorical breath of fresh New England air to clear my mind. Frost is easily one of my most valued companions on the journey of life.

Perhaps it’s because his poetry, simple and down-to-earth, contains so many profound lessons of life. In every poem he seems to capture some universal value or vital message that serves as a sacred window to a greater world of light and life. At the very least, his poems remind his readers of our shared humanity and the values that unite us.

It’s also hard to think of anyone who better typifies the spirit of our nation than this great soul. Most Americans know him through the phrases of his works that have embedded themselves deeply in our national consciousness:

- The road less traveled…

- Good fences make good neighbors…

- Miles to go before I sleep…

And others. It is the poem that contains this last phrase that we will examine.

An Evening to Remember

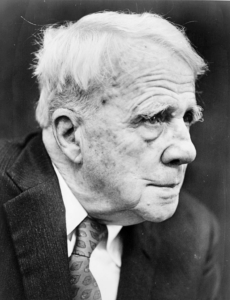

Surprisingly, Frost (1874-1963), who lived as poet in residence at Amherst College in Massachusetts most of his adult life, never finished college. He consorted with kings and presidents (he was John F. Kennedy’s favorite) and has been quoted by academics and the common man for a hundred years – but he was not an academic as we understand that term today.

He was better than that. He was a farmer.

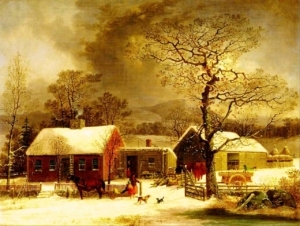

Like Grandma Moses’ artwork, his poems often capture the essence of rural American living and draw out the profound truths that the simpler lifestyle teaches.

He was also a prodigy of poetry. Frost once admitted that he wrote his 16-verse “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” in a matter of a few minutes after a sleepless night spent writing a longer poem.

According to him, after working all night, he walked outside, saw the dawning sun, and was reminded of an experience he had had on a dark evening the Christmas before. He was returning home from a frustrating errand in town trying to sell some produce from his farm to get money to buy his children Christmas gifts but had sold nothing all day. The reverie he felt as he passed by a dark wood on his way home that night gave him the idea and vivid imagery for this poem.

Such bursts of inspiration are the poet’s stock and trade: in just a few short moments of inspired writing about a dark forest, the world suddenly became a brighter place.

His famous poem (written in 1922) turned 100 years old in June of this year and was published in Frost’s collection of poetry called New Hampshire which won him a Pulitzer Prize and solidified his reputation as the un-anointed poet laureate of the 20th century.

Technique

Poetry is much more difficult to write well than prose because the poet has to take into account more than just his own ideas and musings.

- Sound: he has to think about how something will sound when it is read out loud, so he appeals to the hearer’s imagination with vowels, consonants, carefully chosen syllables, and word plays (onomatopoeia, alliteration, etc.)

- Sight/insight: he must calculate how his images and their symbolism will serve to paint a picture for his readers that will help them envision the truth of the message he is trying to get across.

- Artistry: the poet positions his words and phrases precisely where he wants them to fall in the poem for greatest beauty and emotional effect.

- Music: he thinks about rhythm, repetition, and rhyme that will make the poem sound like a piece of music more than a collection of words. (For generations of oral history, poems were sung, not read or even recited.)

When a poet sits down to write a poem he is an artist, not just a writer, almost a sculptor using words as his medium to craft a memorable monument of truth and beauty to enrich the souls of others.

When a poet sits down to write a poem he is an artist, not just a writer, almost a sculptor using words as his medium to craft a memorable monument of truth and beauty to enrich the souls of others.

Frost’s “Stopping by Woods” is all of this. It’s a masterpiece in just sixteen short verses. First let’s read it and then we’ll do a brief analysis of the poem’s structure and literary imagery, ending with the truths Frost’s little horse teaches us. (The letters ABCD at the end of each line signify the sequence of rhymes.)

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

A

A

B

A

B

B

C

B

C

C

D

C

D

D

D

D

Structure

There are a few structural items to note about the poem:

- The only 3-syllable word in the entire poem is “promises”, which in itself emphasizes Frost’s core message of fidelity to one’s commitments;

- The tone is progressive: certain syllables are soft at the beginning (w and th, and double ll); then the tone strengthens in the middle (z, g, and qu); and ends up with harsher consonants at the end (k, b, and p). This progression is significant to the overall message, as we will see;

- The meter of the poem (Iambic tetrameter) is perfectly suited to the sentiment: it is short and compact to express a simple message yet perfectly rhythmic and lyrical at the same time to give a sense of meditativeness;

- The rhymes are synchronized in a kind of chain-link fashion. The third verse in each stanza (as noted by the red highlighted words in the poem above) ends with a word that rhymes with and points to the first verse of the following stanza;

- Only the final stanza breaks this pattern; there is no other stanza for it to link it to, and the repetition of the last two lines is used to add emphasis to the message;

- When he repeats the final line, we almost get a sense of Frost waking up out of a reverie about the beauty he experiences and reminding himself of the burden he must carry for others (actually the horse reminds him!)

Symbolism

Dark wood / Dark evening

Perhaps Frost was harkening back to the medieval poet Dante, who began his epic poem Inferno with the image of finding himself lost in a dark wood. For Dante the forest symbolized being caught in the middle age of life tangled in the thicket of its many crises. Here also, the dark wood also triggers a feeling of the heavy burden of human responsibility that the protagonist carries and maybe a sense of depression at his failure at the market. Like Dante, the deep wood sends Frost deeper into his soul where he finds a longing for an undying world of peace liberated from the burdens and darkness of this world. The longer he contemplates the dark wood, however, the more he sees its intrinsic beauty. By the end of the poem he is calling it “lovely, dark and deep” as if “dark” has lost its menace and is now an attribute of its beauty.

Snow / Wind

In that context of inner longing, the white snow (falling majestically in “downy flakes”) contrasts beautifully with the menacing wood. Wind usually symbolizes the chaotic forces of the world, but this one is an “easy wind” coming off a starkly beautiful frozen lake, seeming to refresh him as he contemplates the snowfall. The contrasting images of light vs dark, heaviness vs lightness, frustration vs refreshment are the two poles of human existence: we live in this tainted world but are destined for another world where, as the Bible says, “every tear will be wiped away” (Revelation 21:4).

Farmhouse / Village

Farmhouse / Village

The human community also enters into Frost’s reverie, although indirectly: the man who owns the property, his home in the village, the sleeping world are all far away. The English Renaissance poet John Donne, wrote that “no man is an island,” but here Frost seems to feel his island-like separation from the rest of humanity as he finds himself in the middle of nowhere struggling alone with his frustration and longing.

The Little Horse and the Contrast of Natures

In my view, the little horse is the critical symbol of this poem. The horse represents the vast world of nature, and his startled reaction to the man stopping in the middle of a journey contrasts nicely with the man’s deeper capacity for wonder and spirit.

Whereas the man is struck by the beauty of the scene, the horse is blind to it. The animal is not subject to a burst of inspiration like the human; he doesn’t wonder at the transcendent.

Rather, the horse remains on task. He is a beast of burden, a creature of the world without the depth of soul that a human being enjoys as a natural endowment. He represents work and the raw, inexorable forces of nature and duty that stop for no man.

Yet, the animal is not a machine either. Frost personifies him in a delightful way: the horse “thinks”, “asks”, and “shakes” his harness bells as if seeking to understand something his nature can’t quite comprehend. His existential limitations symbolize the one pole of human existence – the fleshly – which man cannot escape but which he can transcend in a way the horse cannot.

In other words, man has an inner capacity the animal lacks. The little horse by his very deprivation teaches us what a gift the human soul is.

The beast must follow his nature and work. There is no mystery in his world. The human, on the other hand, can stop and wonder at the beauty he sees. He also must choose to work and to do so for transcendent motives (keeping his “promises”), which are refinements of human nature over animal nature.

Universal Human Experience

Finally, the harness bells.

Like St. Peter on the top of Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration, the farmer wanted to stay on the summit of his experience of deep beauty, but the horse won’t let him. The bells ring, they demand, they call. They symbolize, of course, the wake-up call that besets every person through the press of human responsibilities. If there is anything that can be called a universal human experience, it is the inflexible urgency of human commitments.

Again, the deep capacity of the human soul dominates the message: the man realistically faces all the miles he must go before he sleeps, but he chooses to travel them for the sake of his loved ones because he is not just a workhorse. He is a husband and father, a man of transcendent values. More importantly, he does so in the hope of a better world that awaits him – when his work is finally finished.

—

Sources:

Mary Oliver, A Poetry Handbook (1994), Great American Poets Series: Robert Frost (1986); Poem text in public domain at Wikipedia: “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening”; Photo of Robert Frost, Walter Albertin, World Telegram, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons; all other images courtesy of Pixabay.

Soul Work

Human problems don’t go away by wishful thinking. Frost’s poem is about the mature man who takes the knotty responsibilities of raising a family squarely on his shoulders and embraces them again after finding inspiration in an experience of beauty.

This pattern is reproducible in our lives too. We cannot avoid the press of duty, but we can fortify ourselves for it by deepening our soul’s capacity to see it all in perspective. Analogously, we “see the forest for the trees” only when we step back from the urgency of life’s crises and immerse ourselves in Beauty, Truth, and Goodness for a while.

This is nothing new to the Church, which has given humanity an endowment of transcendent gifts like no other. Perhaps today you can take time out to listen to some inspirational music, read an engaging story, go to a museum or to a performance of wholesome art, etc.

Above all, prayer strengthens the human spirit, and we can do that at any time.

Leave A Comment