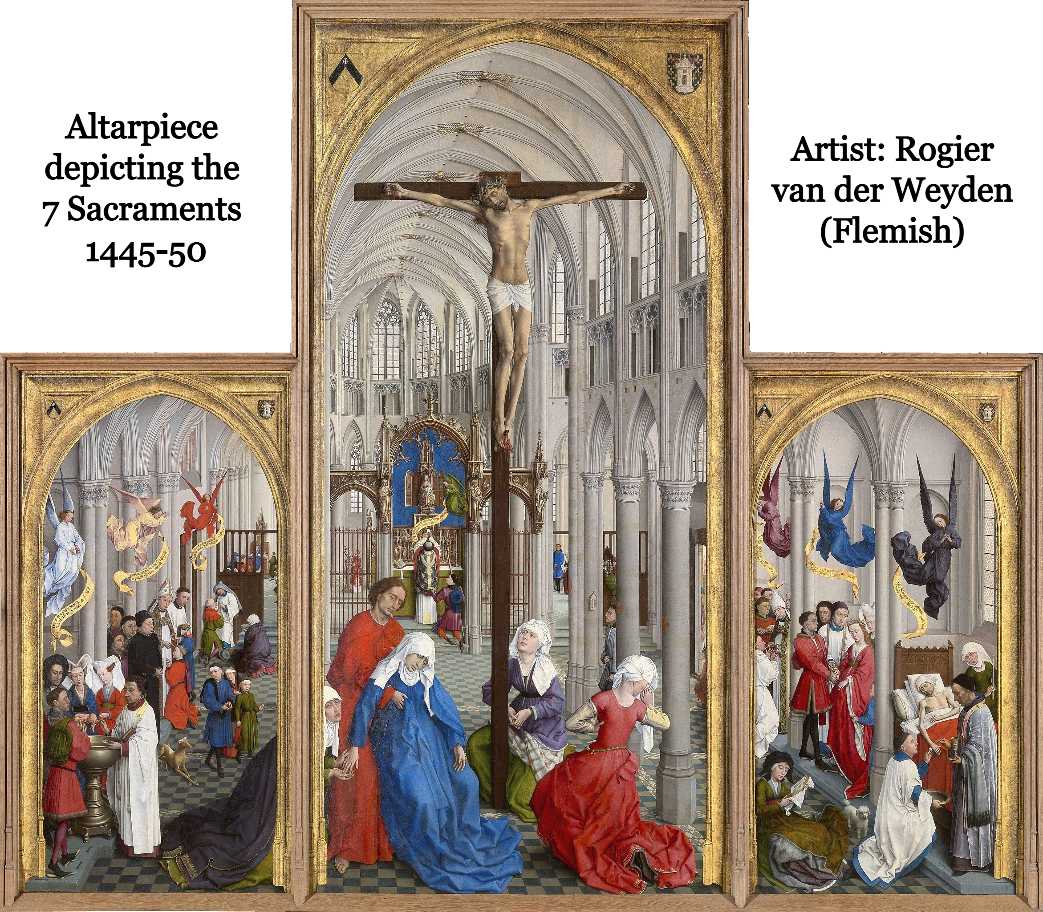

“This is the sweet mystery of life: the Sacraments.”

~Abp. Fulton J. Sheen

Cradle Catholics take it for granted that the number of sacraments is seven. It just is. “It has always been thus,” as the saying goes. But has it?

Well, not really. Or, maybe it’s better to take the lawyer’s position and say, “Both Yes and No” or “It depends.” Let me explain.

Rooted in Scripture

The Yes part of the answer is that the number has always been seven. Above all, it’s not hard to find evidence for the seven sacraments in the Bible. Here is the basic rundown (the citations below are only a selection. Many more could be added):

- Baptism: Matthew 28:18-20; Mark 16:15-16; John 3:1-7.

- Confirmation: Acts 19:3-6; Acts 2:1-13; Hebrews 6:2.

- Eucharist: John 6:30-71; Matthew 26-26-29; 1 Corinthians 11:24-27.

- Penance: Matthew 16:19; John 20:21-23; James 5:16.

- Anointing of the Sick (Extreme Unction): Mark 6:13: James 5:14-15.

- Holy Orders: John 20:21-23; Acts 6:3-6; 1 Timothy 3:1, 5:22.

- Matrimony: Matthew 19:4-6; Ephesians 5:31-32; Revelation 20:1-3.

In other words, the sacraments are all scripturally based, so we should never let anyone tell us that they are non-biblical “inventions” of the Catholic Church. Keep in mind that the sacraments were around from the very beginning of the Church – even before the New Testament was written! They have been guarded in the heart of the Church for twenty centuries.

In essence we are saying that sacraments are the Church’s holiest possessions – more accurately, gifts – because they are of divine origin, and we must always remember that when we receive them. They are the most sacred of all the sacred windows of our faith.

Pope St. Leo the Great said that the presence of God in this world has passed into the sacraments. They are a pretty awesome realities when you think about it.

Number Depends on Definition

Historically, the core problem for the Church was not figuring out the number. The issue was how to define a sacrament, namely, how to determine what qualified as a sacrament and what did not. And that is the No answer: if you don’t know what a sacrament is, just about anything holy can be a sacrament, and that number isn’t limited to seven.

One very clever theologian in the early middle ages, for example, thought that there were thirty sacraments! His name was Hugh of St. Victor, and please don’t blame him for his theology because he just thought that other holy things such as holy water, blessed ashes, the sign of the cross, and the taking of religious vows, among others, were also sacraments.

It was an honest mistake. We take the seven sacraments as a given, but it wasn’t always so. Such a saintly man as St. Peter Damian thought the consecration of kings was an eighth sacrament. The famous theologian, Peter Abelard, believed the number of sacraments was six, and other theologians of the day thought there were five or twelve. (Old Hugh takes the cake with thirty, however.)

This diversity of numbers came about because the Church hadn’t settled on a clear definition of a sacrament, as distinct from a random holy thing.

The issue was finally settled in the year 1213 when the Fourth Lateran Council fixed the number of sacraments at seven; the Church reaffirmed the number seven again at the Council of Florence in 1439; and then definitively at the Council of Trent (1545-63).

Now, I know what you must be thinking: “You mean it took 1,200 years to define the number of sacraments?!” I get your dilemma. It seems like the Church was a little slow on the uptake! This was not an easy matter for the Church to get right. But why, exactly, did it take so long?

An Organic Process

First of all, since the Church didn’t invent the sacraments, the full understanding of them took place through an organic process of development, which of course, like any natural process, took time.

Joseph Martos, in his book Doors to the Sacred, says that one reason it took so long is because the Church was pretty busy for a few centuries. For example:

- From the time of Christ to the Roman Emperor Constantine (313 AD) the Church was fending off one violent persecution after another. During these centuries, the Church took for granted that the sacraments had been handed on to them by the Apostles.

- The Fathers of the Church (roughly 200 to 700 AD) then spent a good deal of time on doctrinal controversies and on clarifying critical doctrines like the divinity and humanity of Christ. But they didn’t define the sacraments because these were lived realities, not disputed matters.

- After that, the Church was too busy evangelizing and converting all the pagan tribes of Europe in the centuries following the Fall of Rome (roughly 500-1000 AD). Finally,

- The Crusades happened: there were as many as eight Crusades from 1096 to 1270 AD, and, needless to say, it’s hard to write books when the majority of a nation’s youth are off conquering and defending foreign lands.

Martos goes on to say that the rise of several new religious orders in the Middle Ages, particularly the Dominicans and the Franciscans, together with the establishment of universities, led to a precise definition of what a sacrament is.

Here again we have another Catholic marvel. The great medieval universities grew out of Catholic cathedral schools: Oxford was established about 1096; University of Paris, 1150; University of Padua, 1222, among others. These centers of culture and faith systematized higher learning and allowed scholars to get into the depths of teachings that had formed the foundation of the Church’s life for a thousand years. Says Martos:

The monks and schoolmen were looking for a coherent understanding of the Christian religion, but they found themselves confronted with a bewildering variety of texts: sermons and letters, commentaries and treatises, statements of bishops and councils. So in order to make some headway through this mountain of information, early medieval scholars began making summaries of what they read and collecting quotations on various subjects such as the incarnation, the Trinity, the church, and so on. (Martos, Doors, 49-50.)

That’s when the real smart churchmen of the Middle Ages (men like St. Albert the Great, St. Thomas Aquinas, and St. Bonaventure) began to make the necessary distinctions that solidified our concept of what a sacrament is.

Greater Precision

A precise definition of a sacrament came from a scholar at the University of Paris named Peter Lombard (1096-1160 AD), whose collection of ancient writings, The Sentences, was read by everyone who got a higher education. He was the first one to make a certain crucial distinction about holy things which was critical to defining the number of sacraments. He said,

A precise definition of a sacrament came from a scholar at the University of Paris named Peter Lombard (1096-1160 AD), whose collection of ancient writings, The Sentences, was read by everyone who got a higher education. He was the first one to make a certain crucial distinction about holy things which was critical to defining the number of sacraments. He said,

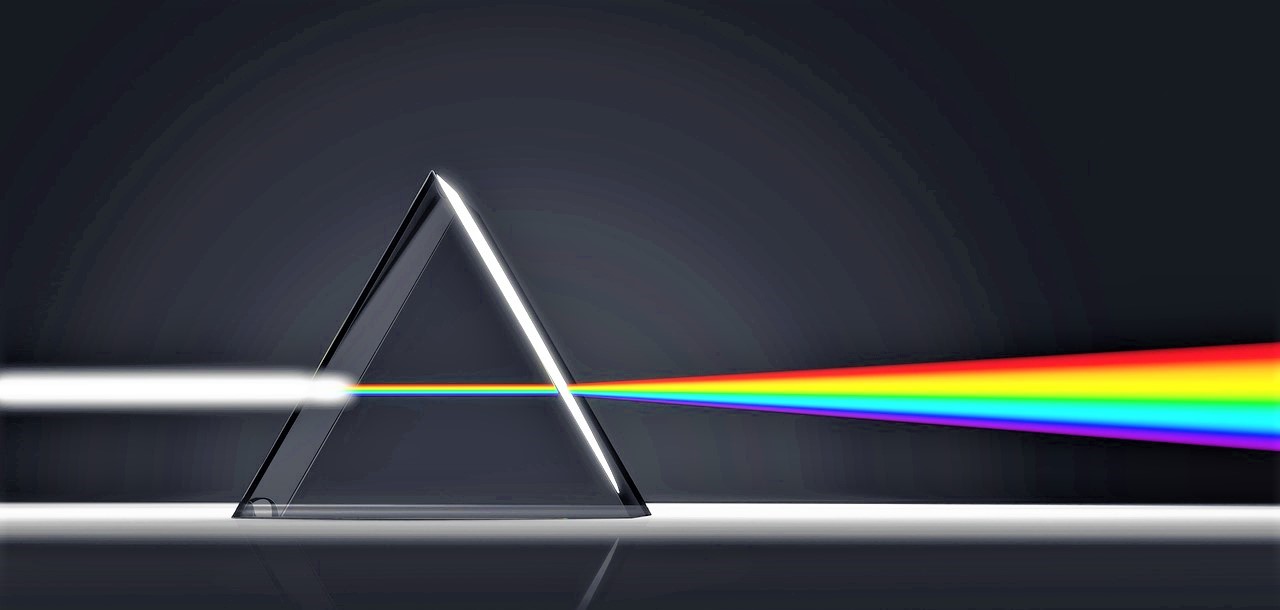

- A holy thing can be either a sign of holiness, or

- It can be both a sign of holiness and a cause of that holiness.

Bingo! This distinction has come down to us as the difference between a sacramental (just a sign) and a sacrament, which is both a sign and a cause of grace. (With distinctions like that, I would have thought Lombard was a Jesuit, but the Jesuits wouldn’t come on the scene for another 300 years. He was a Franciscan….)*

Did you also notice the dates? Lombard died in 1160 and the first formal definition of the number of sacraments was at the Lateran Council in 1213. In other words, once the Church got clarity on the very essence of what a sacrament was, it was not hard then to formalize it into doctrine. This is the way things operate: whenever the Catholic hierarchy defines something, it’s not because the Church “invented” it! It’s usually because the Mystical Body of Christ had mulled it over for a few centuries to get clarity on its deeper meaning for our souls.

A Crucial Distinction

This also brings us right back to the crystal clear definition of the ever-reliable Baltimore Catechism:

“A Sacrament is an outward sign instituted by Christ to give grace.”

That distinction, for example, shows the difference between holy water and the sacrament of Baptism. Holy water is a holy thing because of its blessing by a priest, but it is not a sacrament; yet, it can be used in the action of the Sacrament of Baptism to actually give us grace. The same goes for the different oils used in Baptism, Confirmation, Holy Orders, and Anointing as well as for other material elements such as bread and wine.

Sacramentals may also consist of words and gestures, not only physical elements. For example, the sign of the Cross is a reminder of Christ’s Crucifixion, but a priest making the sign of the Cross over a penitent and pronouncing the words, “I absolve you…” is a sacrament.

Whole courses can be taught on the sacraments, so we will have to limit ourselves to the question of why there are seven sacraments, and not six or eight (or thirty!) But look for more articles to come on these wonderful sacred windows.

Symbolism of the Number 7

Finally, as to the number, seven is often called the “perfect number” in scripture, and there is a reason for that:

Four symbolizes the natural world (four corners of the earth, four directions, four winds, etc.), and three, of course, symbolizes the life of God (the Trinity).

Seven is the sum of those two numbers and thus represents a fusion of the natural and supernatural, the human and the divine, indicating that anything which bears that number is able to transcend heaven and earth.

That’s another way of saying that the sacraments came down from heaven – and more importantly – raise us up to the very life of God.

———-

*Fulton Sheen, Life is Worth Living, Audio CD set, #25 – “The Seven Rivers of Life,” St. Joseph Media, 2019.

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 2/5/23, so it does not end with the regular Soul Work section. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

*(Correction: It was incorrectly stated that Peter Lombard was a Franciscan. Rather, he was a secular priest and served as bishop of Paris for a year before his death.)

Leave A Comment