When I spoke about the Pre-Raphaelite phenomenon in a recent Sacred Windows piece, I was describing a movement that was a rebellion of sorts—a typically polite English uprising. The French, however, had their own version of this rebellion, and it came via the often flamboyant and chaotic animators of Impressionism.

What, exactly, were they rebelling against? Well, in short, they didn’t like the “Christmas Card artist” I will speak of today—or his ilk.

This Frenchman, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and his English counterparts like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainesborough, were the artistic targets of the rebels who wanted to break out of the strictures imposed on art by the Royal Academy of Art in London and the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

This Frenchman, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and his English counterparts like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainesborough, were the artistic targets of the rebels who wanted to break out of the strictures imposed on art by the Royal Academy of Art in London and the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

The rebels thought that art had degenerated into banal repetitions of tired themes (classical formalism), and they might have been right. Or at least one could understand why this younger set of idealists wouldn’t want to be held back by the constraints of their elders. Boring!

In response to the encrusted artists of the day, the English preferred a return to pre-Renaissance realism—a kind of harkening back to an age of faith and chivalry—while the French preferred breaking out into unfettered free expression (shocking, I know.) It was inevitable that these movements would generate a sort of internal war in the art community.

So, who won? Happily, both sides did!

The Triumph of Beauty

While much, but not all, beauty is a matter of personal preference, art must still appeal to certain standards—such as unity, radiance, proportion, integrity—in order to have a lasting impact and a following that doesn’t dissipate after half a generation. Cheap art, which just stimulates superficial emotions, never endures.

That’s why both movements won. The classical style of the French and English schools had its own remarkable beauty, even if the young turks of the time didn’t like it. The rebel movements also created some amazingly wonderful art before their fragile efforts diverged into other fields or fractured into bizarre strains of modern art that only appeal to certain personality types.

That’s why both movements won. The classical style of the French and English schools had its own remarkable beauty, even if the young turks of the time didn’t like it. The rebel movements also created some amazingly wonderful art before their fragile efforts diverged into other fields or fractured into bizarre strains of modern art that only appeal to certain personality types.

Bouguereau, a classicist, painted such immensely beautiful imagery, particularly of women, that, to this day, we can enjoy his brilliance on innumerable religious cards and calendars. Most of us are unaware of the talent who created them all. They’re just beautiful and apt to the season, so we never get tired of looking at them.

He lived from 1825 to 1905 and died just shortly before his 80th birthday. He is said to have created 822 works of art in his professional life (not counting sketches). That is extraordinary. It is thought that Rembrandt, for example, produced only about 300 paintings; Caravaggio, only about 100; and the incredible Vermeer, only 34.

Although many familiar and famous artists have been extremely prolific (Van Gogh, 860 paintings; Rubens, 1400 paintings; and Charles Schultz, 28,000 Charlie Brown comic strips!), Bouguereau ranks as one of the most prolific painters ever to light up the world with his talents.

Although many familiar and famous artists have been extremely prolific (Van Gogh, 860 paintings; Rubens, 1400 paintings; and Charles Schultz, 28,000 Charlie Brown comic strips!), Bouguereau ranks as one of the most prolific painters ever to light up the world with his talents.

His professional life showcased an astounding versatility and breadth of subject matter. He painted portraits for private patrons of high society as well as hundreds of renditions of simple, humble peasants. His art was for private homes, public buildings, and international shows. He taught literally thousands of students during a nearly sixty year career.

His Madonnas

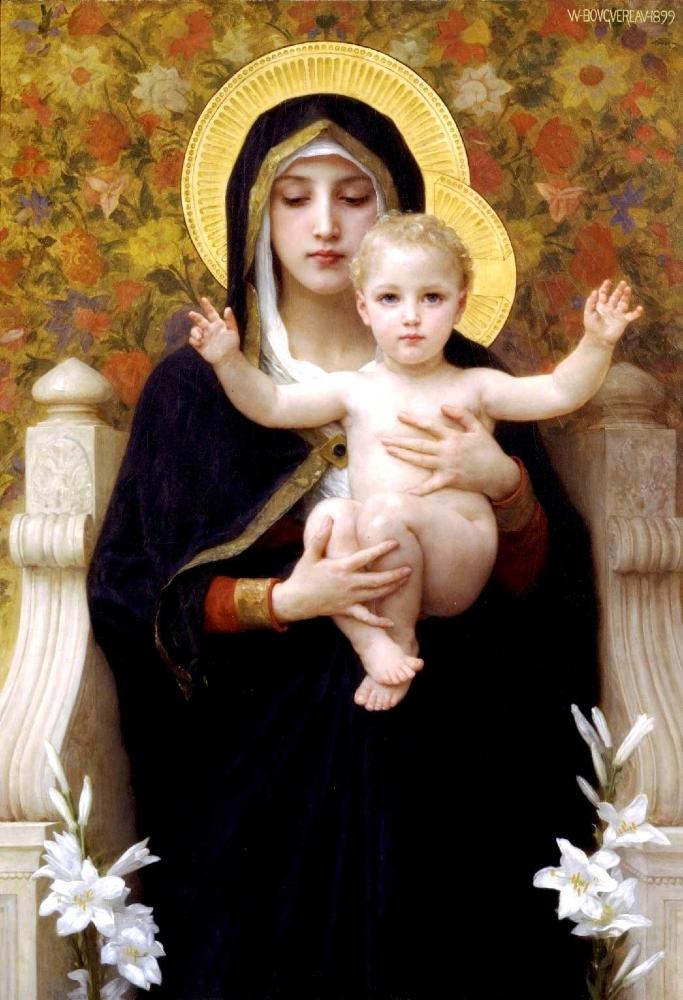

Yet, I think his greatest single subject seemed to be the Blessed Virgin Mary in the classical form of the Madonna (Mother and Child). In canvas after canvas we see variations on the same theme and even images of peasant mothers poised in unique Madonna-like poses with their children.

I probably don’t need to tell you that the Madonnas are what made him a Christmas card painter for the ages (though he likely never intended for his art to be commercialized that way). They are wonderful, and you’ll see a few of his most famous Madonnas below.

The French art scene during much of Bouguereau’s long career was often focused on pagan mythology. I don’t know about you, but I can only take so much of Persephone being carted off to the underworld by her uncle, Hades, or nymphs frolicking in the Elysian Fields.

Bouguereau certainly painted a ton of art reflecting pagan mythology, which is beautiful in its own right but not the pinnacle of his artistic expression.

What is little known about him is that his uncle Eugène was a Catholic priest (the artist’s portrait of le bon père at left) and inspired in the young artist a love of beauty in literature, nature, and faith. For a time in his youth, Bouguereau was studying for the Catholic priesthood but soon realized his true vocation was to art. From his early twenties, he dedicated himself to advancing in this profession.

What is little known about him is that his uncle Eugène was a Catholic priest (the artist’s portrait of le bon père at left) and inspired in the young artist a love of beauty in literature, nature, and faith. For a time in his youth, Bouguereau was studying for the Catholic priesthood but soon realized his true vocation was to art. From his early twenties, he dedicated himself to advancing in this profession.

Still, we can see in his Madonnas the influence of his early formation in the faith, even if certain aspects of his life did not always adhere to that faith with the same vigor. There but for the grace of God go all of us.

A Few of His Sibling Portraits

Another constant theme of Bouguereau’s is family, children in particular. I’ve written before about his love for the simple innocence of childhood. It is one of his many marvelous contributions to art, in my estimation.

Here are just a few of his enchanting depictions of children and their siblings together (mostly in rural scenes). I can’t get enough of these!

Beauty in the Midst of Tragedy

Perhaps his wonderful children and sibling portraits are a reflection of Bouguereau’s grief for the children he himself lost: he outlived four of his five children. Can you imagine?

One child died in infancy, and three of his children died of tuberculosis (a little girl at age 5 and two boys at ages 15 and 32.) Coupled with the death of his first wife in 1877, these tragic deaths were spaced out over a period of 32 years (1866 to 1900), so the artist was never without his share of heart-wrenching sorrow to accompany his art throughout his whole long career.

One child died in infancy, and three of his children died of tuberculosis (a little girl at age 5 and two boys at ages 15 and 32.) Coupled with the death of his first wife in 1877, these tragic deaths were spaced out over a period of 32 years (1866 to 1900), so the artist was never without his share of heart-wrenching sorrow to accompany his art throughout his whole long career.

(Image at right: his eldest daughter, Henriette, with her infant brother Paul.)

I wouldn’t wish that kind of sustained agony on anyone, but it’s clear that Bouguereau had developed an enormous ability to channel his grief into magnificent art. It is the mark of a truly great soul and may be the best way to bring something good out of so much pain and sorrow.

His Madonnas

I like his Madonnas better than his rustic sibling art because of the religious theme, but each genre is ravishing in its own right. He also painted many other holy scenes, but by far, the ethereal beauty of Madonna captured Bouguereau’s religious imagination more than any other. He seemed to have the same penchant for painting Our Lady as Botticelli whose love for Madonnas was just as vibrant and his painting just as vividly beautiful.

It’s not clear how many Madonnas (or Madonna-like representations) Bouguereau painted overall, but I’d like to leave you with six Christmas card images to spur your Advent imagination and to help you to prepare your heart for the coming of Mary’s Son at Christmas.

(Notice the Child in 3 of the 6 with his arms outstretched welcoming all!)

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 12/8/24. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Photo Credits: All Bouguereau paintings via Wikimedia and in the public domain.

Leave A Comment