You may be surprised to know that the word “hour” in the Catholic tradition doesn’t mean sixty minutes of time. Our Tradition embraces a more qualitative sense of time or at least more general timeframes than we are used to in our world of time mastery and technical precision.

We’re familiar with this traditional way of reckoning time from scripture: the Gospel of John, for example, says that Pilate condemned Jesus at “the sixth hour” (John 19:14) –noon – a typical way of measuring time in the ancient world before the invention of the clock.

Of course, we conduct our lives in the world of chronological hours, but the concept of an “hour” in the Catholic mind is not really about time: it’s about prayer. Hours are more like sacred spaces in the day when we take “time out” to sanctify our work and daily lives by prayer.

The jewels of prayer that our title speaks about are based on this more generalized and qualitative concept of time, and we’ll appreciate them better with a little explanation of the system of prayer that produced them.

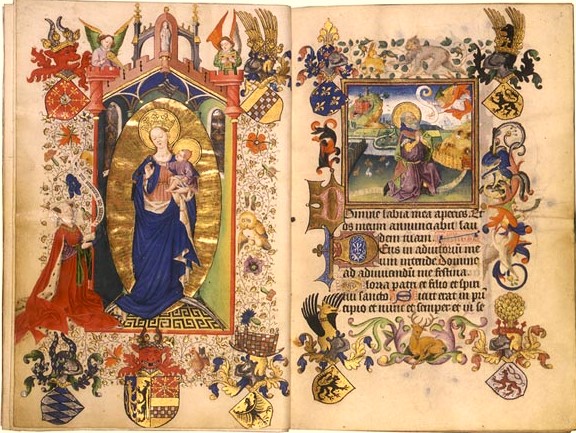

Saint Anne presenting a young Virgin Mary and Anne of Brittany to her patron Saint Claude.

From the Primer of Claude of France, ca. 1505

Hours and Prayers

First, the word itself. The English word “hour” comes directly from the Greek word hóra (Gk: ὥρα) with a hard “h” at the beginning.

The Latin language adopted the word directly, keeping the “h” but making it silent. So hóra is actually pronounced “ora” in Latin, which is precisely the word for “prayer” in Latin! (The verb “to pray” is “orare”.)

These two words – with and without the “h” – are fraternal twins, we might say. When the word is used to designate time, it keeps the initial “h”, which we see reflected in the uncommon English word for “schedule” (horarium). When it is used for prayer, it loses the initial “h” as in our word “oration”, etc.

The connection between the two words may be coincidental, but it is likely – very likely – that the ora for prayer came from the fact that the prayers were conducted at fixed hours of the day in both the Jewish and Christian traditions. There is some biblical precedent for this in the psalms:

“Seven times a day I praise you because your judgments are righteous” (Ps 119:164).

This scriptural witness for daily prayer is the basis of what developed over centuries in the Christian monastic Tradition.

St. Benedict (Again)

I’ve written in the past about the contribution of the amazing St. Benedict (480-548 AD) to the transformation of Western civilization. His feast day is this week (July 11th), and each time it comes around I always marvel that one man could have had such a great impact on history. His monks essentially saved the West after the fall of the Roman Empire, and they spread learning and culture everywhere they went.

I’ve written in the past about the contribution of the amazing St. Benedict (480-548 AD) to the transformation of Western civilization. His feast day is this week (July 11th), and each time it comes around I always marvel that one man could have had such a great impact on history. His monks essentially saved the West after the fall of the Roman Empire, and they spread learning and culture everywhere they went.

The other aspect of the Benedictine influence on civilization was prayer. As part of their Rule of Life given by St. Benedict (in the year 516), all monks dedicate themselves to praying the psalms together with their community at certain hours of the day. This routine of monastic prayer is called the Liturgy of the Hours and is based upon the “seven times a day” reference from Psalm 119.

Then, the Benedictines went the extra mile and found another prayer reference in the same psalm which increased their prayer regimen to eight times a day!

“At midnight I rise to praise you because of your righteous judgments.” (Ps 119:62)

While St. Benedict did not invent this system of prayer, he certainly standardized it and made it a way of life for centuries of monks and, as we will see, for the laity as well.

The Horarium of Prayer

Monks pray at eight different “hours” of the day. This does not mean that they sit in a church for eight continuous hours every day praying! Again, that is the chronological meaning of the word hour. Still, eight different prayer times during the day is a lot of prayer.

It indicates that every single day, while the laity go about their business working jobs in the world, monks in monasteries and nuns in cloisters are doing their own “work” praying for the world in a formal way, roughly every three hours – including in the middle of the night.

This schedule of prayer is also called the “divine office”, and again, there is a very logical reason for that term: “officium” in Latin means “duty”. It is the duty of monks, nuns, priests, and religious to pray for us – how nice!

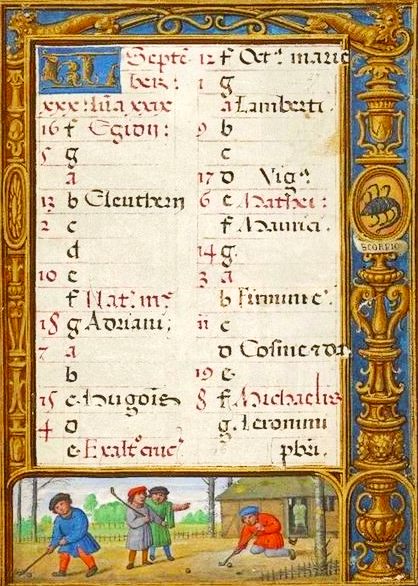

(Left) Upper Panel: Church calendar. Lower Panel: Four men playing a game that looks like medieval golf!

(Right): Opening words of the Hail Mary (Ave Maria in Latin).

Religious men and women obviously take prayer seriously. While the world goes crazy with its political upheavals and social chaos, they are sitting in churches behind monastery walls placidly interceding for the world. And they have been doing so in a structured way for more than 15 centuries.

Undoubtedly, these consecrated souls are probably the reason our wretched, sinful world doesn’t collapse into utter anarchy on a daily basis.

Jeweled Prayers for Active People

When other religious orders arose in the 12th century, like the Franciscans and Dominicans, they began to carry around an abbreviated book of Psalms called, appropriately, a Breviary. That way, they could continue the tradition of praying eight times a day even while conducting their ministries outside monastery walls.

When other religious orders arose in the 12th century, like the Franciscans and Dominicans, they began to carry around an abbreviated book of Psalms called, appropriately, a Breviary. That way, they could continue the tradition of praying eight times a day even while conducting their ministries outside monastery walls.

The laity too got in on the deal, especially in the Middle Ages when the profoundly religious culture of Catholic Europe began to produce various types of prayer books for the average literate believer to use. These contained psalms like the monks’ prayer books but also added devotional prayers, Mass and scripture readings, artwork, calendars of feast days, and hymns, among other things.

There is nothing new under the sun, they say. The nicely decorated prayer book you might use when you go to Mass or pray in an adoration chapel may be unique in its modern printing and design, but it is not a new concept. Its roots lie in the fantastically-decorated prayer books of the Middle Ages.

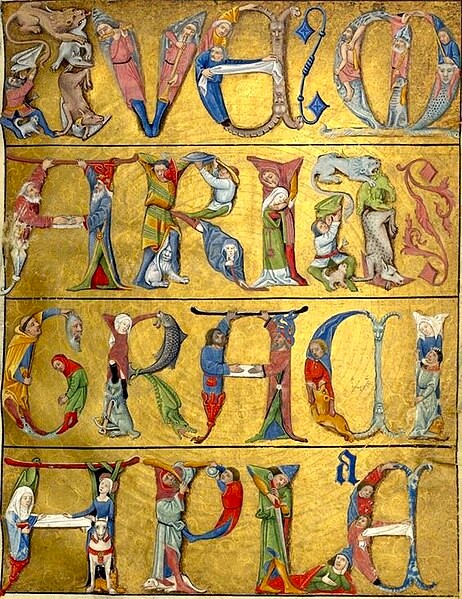

Illuminated Pages

Here, we come to the truly beautiful tradition of illuminated prayer books. By “illumination” we mean painted decorations that were added in and around the words of a hand-printed manuscript. I wrote earlier about the magnificent Book of Kells which is one of the best examples of an illuminated manuscript ever, but the early decorated Bibles were only the beginning of this art form.

The illuminated prayer books of the Middle Ages may be even more impressive as they represent the long-term refinement of this art form. They are nothing short of little jewels of prayer.

For obvious reasons, these books were mostly produced by the nobility who had the money to pay for scribes and artists to create them, although they are not as rare as one might think. One can find tens of thousands of these medieval books in various museums and libraries around the world.

The “market” for these books, however, was quite demanding in the Middle Ages, so the costs went down as many enterprising individuals took care to produce these books for those who wanted them. The best manuscripts, however, were always commissioned by the noble and royal families of the nations.

Here is a list of 58 of the most famous and complete “Books of Hours”

Since there were no strict rules for the production of these books, they are all unique works of art of the highest order, ranging from straight text-only books to manuscripts with exquisite calligraphy, illuminated capital letters, and decorative artwork on full pages.

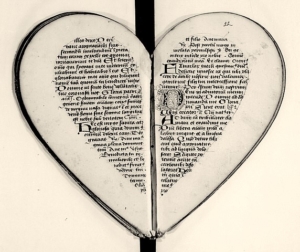

My favorite types of prayer books from that era are the ones crafted in the shape of a heart.

My favorite types of prayer books from that era are the ones crafted in the shape of a heart.

Left: They are called, appropriately, “cordiforme” prayer books (heart-shaped)

Right: And they also appear as decorated music manuscripts.

You’ve seen a few impressive examples of prayer book illuminations so far in this newsletter. Here are a few more:

The Masters of the Craft

One final note of some importance. We probably have to place the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1440 AD) under the rubric of “no good deed goes unpunished.” As transformative as that invention was, it literally wiped out the industry of hand-producing illuminated manuscripts – a sad consequence of a good thing.

It is believed that the Farnese Book of Hours was the final major illuminated manuscript created. It was produced in Italy by Croatian-born Giulio Clovio for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in 1546. Clovio was the last of the master craftsmen illuminators whose industry came to a screeching halt after book printing began to dominate the literary culture.

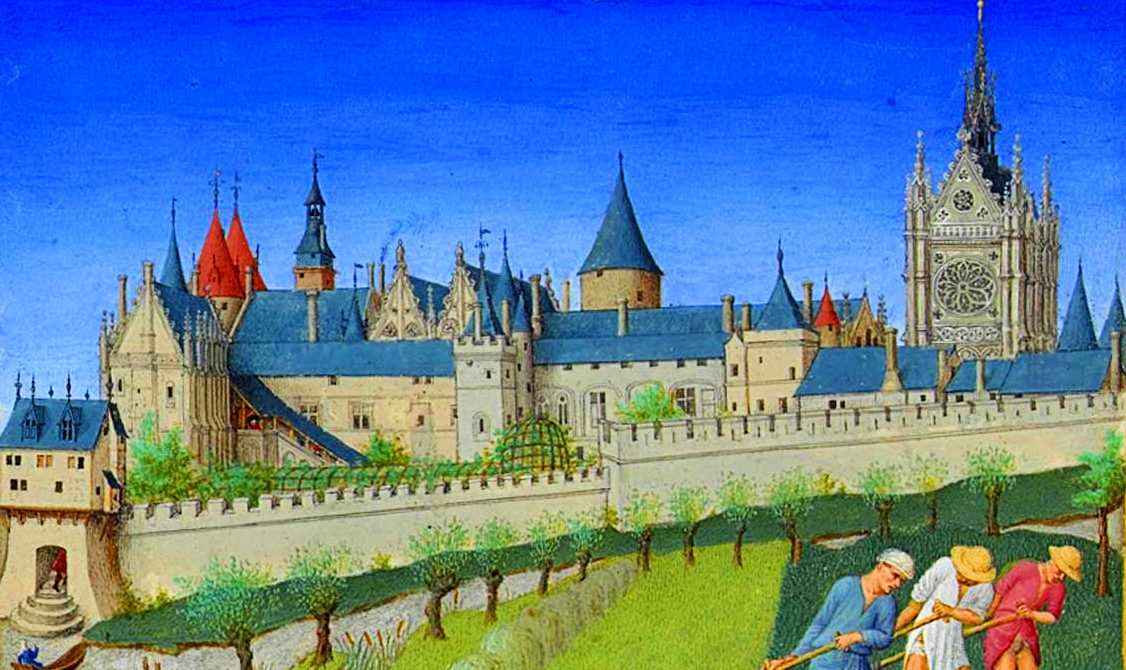

A century prior to him, however, the uber-talented Limbourg Brothers (Herman, Paul, and Johan), produced one of the finest works of art known to man: the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The Wikipedia entry for this work calls it “possibly the most valuable book in the world” – who would have known?!

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

“The Very Rich (Decorated) Book of Hours of the Duke of Berry”

Jean, the Duke of Berry, a member of the French royal family and a patron of the arts par excellence, commissioned the massive project. Duc Jean found his muses in the three Dutch brothers, who became the virtual gold standard of manuscript illumination in the late Middle Ages.

Jean, the Duke of Berry, a member of the French royal family and a patron of the arts par excellence, commissioned the massive project. Duc Jean found his muses in the three Dutch brothers, who became the virtual gold standard of manuscript illumination in the late Middle Ages.

The brothers began their work in 1409, which was sadly cut short when all three of them – and the Duc himself – died of the plague in 1416. Examples of untimely ends like this often remind us to be grateful to God for what we have and the time He has given us!

There is much to explain about this beautiful manuscript, but it’s probably better to let it speak for itself. We will finish with a small presentation of images from this book, and as a bonus, I have placed a larger gallery of their work on another posting of this website for you to view if you wish. [View Limbourg Gallery of Images.]

To conclude by restating our theme: Even one “hour” spent marveling at these min-jewels of prayer from our tradition would be “time” well spent!

———-

Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 7/9/23, so it does not end with the regular Soul Work section. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.

Photo Credits: All prayer book images are via Wikimedia (Trés Riches Heures; Limbourg Brothers; Book of Hours) and are in the public domain. Breviary: King Baudouin Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons; St. Benedict, via Pixabay.

Leave A Comment