Discounting the attempted thefts of this magnificent work of art, the Ghent Altarpiece has been stolen in whole or in part six times in its six-hundred-year history. That’s far more than the Mona Lisa (which was stolen only twice)!

Maybe that’s because the Belgian masterpiece is truly one of the most fascinating works of art ever created by the hand of man. Maybe also because it’s an image of our Lord Himself, a perennial sign of contradiction to the world. I’ll get to the artistic details in a minute, but we first need to know something about its creators. They were two amazingly talented brothers.

The Van Eycks

Sometime around the year 1425, a Belgian nobleman named Jodocus Vijd commissioned Hubert Van Eyck (1366-1426) to paint an altarpiece for the Church of St. John the Baptist in the city of Ghent (today that church is called St. Bavo Cathedral).

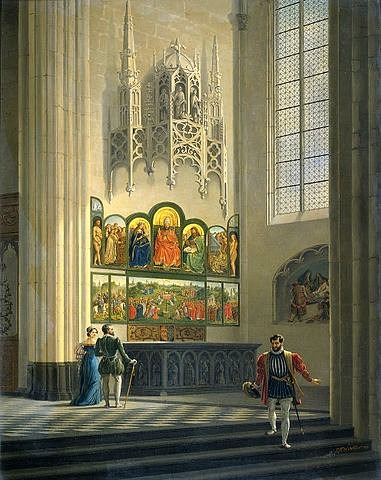

St. Bavo Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium

Ghent Altarpiece during the Renaissance

Sacred Windows readers may remember from a recent newsletter that an altarpiece is different from a reredos (literally a whole decorated wall that serves as the backdrop for an altar). An altarpiece, in contrast, is a work of art attached to the back of the altar itself and towers above it, usually with Eucharistic themes.

Although we know very little about him, Hubert is credited with designing this altarpiece—a work of engineering more than a work of art—but is said to have created some of the earliest sketches and maybe even preliminary drafts of the paintings. He could do no more: a year after he began the project he died.

His younger brother, Jan, inherited the project and went to work. Jan’s self-portrait as an older man shows him wearing a red turban. I don’t know about you, but I can’t get enough of that turban! And check out his signature—it reads like an uber-elegant piece of Latin graffiti: “John of Eyck was here + 1434 +”!

Jan was probably Hubert’s assistant and already involved in every detail of the creation of the altarpiece, but Hubert only launched the project. It was Jan who, after two years of full-time painting, shepherded the project to completion in 1432.

Hubert would have been proud of his little brother, who created a timeless masterpiece. In an inscription only found on the frame several centuries later Jan gave credit to Hubert as the artistic genius who was responsible for it. But his tribute to Hubert must have come from a truly humble heart. Jan the painter was the real genius.

The only personal defect I can detect in Jan, in my humble opinion, is that he worked on commissions for the treacherous medieval villain, the Duke of Burgundy (misnamed Philip the Good) who was the arch nemesis of St. Joan of Arc and is most responsible for her death. (But the altarpiece is so wondrous that I’m inclined to forgive Jan for his momentary lapse of judgment.)

The Mechanics and Facts

In the Middle Ages, altarpieces like the Van Eycks’ creation were immensely popular art forms. They consisted of interconnected panels depicting saints and religious scenes meant to be stationed atop altars as inspirational art. Two-paneled altarpieces are called diptychs, three-paneled are triptychs, and those composed of multiple panels are called polýptychs. The Ghent Altarpiece is easily the greatest example of a polýptych.

Altarpieces were normally meant to be opened on Sundays and feast days but closed at all other times, so they usually have artwork on both the front and the back, which makes them immensely complex and interesting works of art. Click the button below to see a fascinating 6-second animation of the opening and closing of this altarpiece.

Here are a few of the artistic facts about the famed Ghent Altarpiece:

- It rises above the altar at 11.5 feet high.

- When opened to its full extent it is 15 feet wide (wow!)

- When closed, it is the same height but half the width (7.5 feet).

- It is made up of 20 panels, 12 on the front (open) and 8 on the back (closed).

- The front consists of two levels of panels, while the back has three levels, which will be evident in the before/after picture below.

- Each individual panel would be its own masterpiece of religious art if it were not part of a larger work.

- It is also one of the first oil paintings in history, certainly one undertaken on such a massive scale.

- When closed, the eight panels display a monochrome work of art with statues that look three-dimensional, as well as subdued colors on the other panels.

- When opened, it turns into a panorama of color.

One writer perceptively noted that the transition of the altarpiece from closed to open looks “as if the makers of the Wizard of Oz derived their inspiration for a black-and-white Kansas and a technicolor Oz, from Ghent.” Well-said. The Van Eycks had Hollywood beaten by five centuries!

In fact, it was shortly before the Wizard of Oz came out (in 1939) that a most incredible theft of the Ghent Altarpiece took place. That too, is part of a story right out of Hollywood, as we will see.

A History of Theft and Mistreatment

To say that this work of art lived a tumultuous life is probably an understatement. It survived at least three wars and, as I mentioned, six thefts. Most notoriously, the main panels were stolen by Napoleon’s troops in 1794, but France gave them back to Belgium after Napoleon was deposed in 1815.

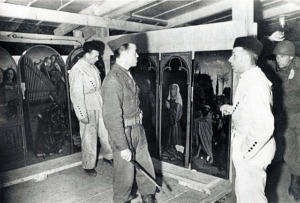

In the following century, the Nazis (1940) pilfered the entire altarpiece during their occupation of Belgium and took it to Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria where they catalogued all their stolen art. They then transferred it to the Altaussee salt mines near Salzburg, where the Nazis had hidden over 8,000 of their most valuable heists.

A group of art detectives rescued it in 1945 when one of Hitler’s henchmen planned to blow the whole salt mine to smithereens! That story actually made it into the 2014 movie named The Monuments Men. The main character, played by George Clooney, called the Ghent Altarpiece the greatest work of art in western civilization. Sometimes Hollywood gets things right.

A group of art detectives rescued it in 1945 when one of Hitler’s henchmen planned to blow the whole salt mine to smithereens! That story actually made it into the 2014 movie named The Monuments Men. The main character, played by George Clooney, called the Ghent Altarpiece the greatest work of art in western civilization. Sometimes Hollywood gets things right.

But history adds more insult to injury. As I alluded to above, in 1934 an opportunistic thief stole a single panel from the lower left corner of the artwork and demanded a ransom. Unfortunately, it was one of dozens of ransom notes that arrived after the theft creating a mass of confusion. Then the real thief returned the back half of the panel as a gesture of good will hoping that he would get the ransom, but the Church never paid it. It remains missing to this day. A copy was substituted in its place.

You get the whole sordid “picture” I’m sure. You can also understand why today the Ghent Altarpiece is housed behind a display case of bulletproof glass in a climate controlled and highly secure section of the cathedral! Better late than never, right?

A Modern Painstaking Renovation

Actually, the greatest damage done to the six-hundred-year-old work is due more to its caretakers than its thieves! For example, a well-meaning curator once actually sawed a number of the front and back panels apart so they could be displayed together without having to open or close the entire altarpiece (ugh!).

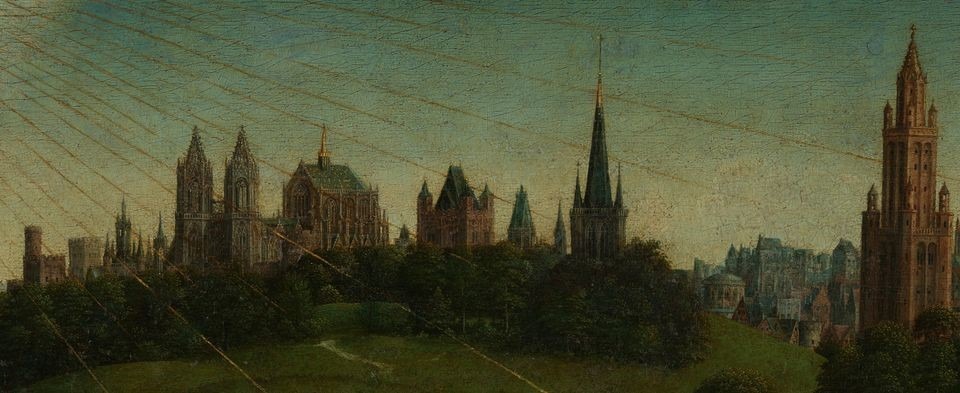

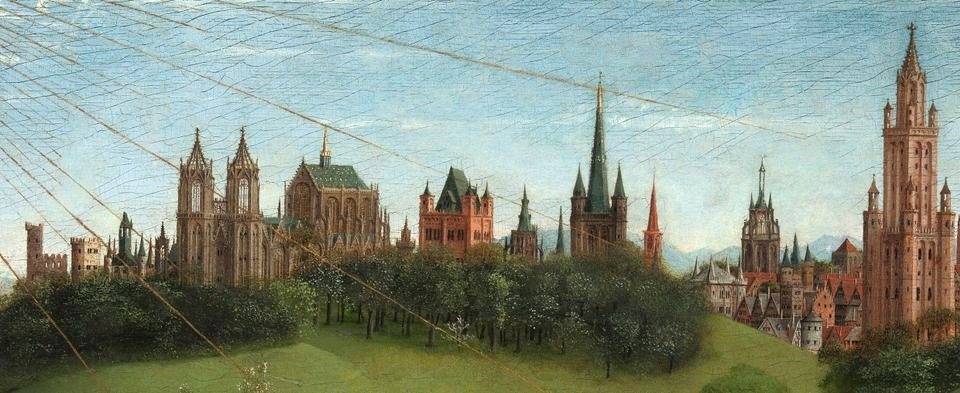

The Van Eycks’ masterpiece has been subjected to dozens of feeble touch-ups and attempted renovations over the centuries that eventually covered about 70% of the entire painting and nearly inflicted permanent damage on the immortal work. I say “nearly” because it appears that the most recent modern restoration has corrected most of that damage—thankfully. (One of the “touch-ups” actually painted over a whole building on the horizon of the lower level. Major ugh!)

On that matter, in 2009 the Belgian Ministry for Cultural Heritage began a painstaking restoration of the entire altarpiece, from head to foot, both frames and paintings. The restoration work was carried on in a special room of the cathedral where onlookers could pass by and look in on the restorers through glass panels to see the progress in real time. The work on the back and the bottom half of the front was completed in 2019.

Here is a before-and-after image of the 8 back (i.e., closed) panels, which gives an indication of the amount of dirt, grime, and aging varnish that was removed in order to restore it to the conditions of Van Eyck’s original. The transformation is truly beautiful.

The Key to the Kingdom

A complex work of art—especially a religious one—needs to be interpreted to get at its deeper meaning, and the Ghent Altarpiece is no exception. Van Eyck, however, has made it easy for us to discover the key for interpretation; it’s the Trinity, or more specifically, the Trinitarian life.

When you look at the wide display, your eye is naturally drawn horizontally across the impressive panorama of images, but take another look. If you view it vertically, down the center of the image, you have the key.

When you look at the wide display, your eye is naturally drawn horizontally across the impressive panorama of images, but take another look. If you view it vertically, down the center of the image, you have the key.

- God the Father is seated on His throne at the top blessing the universe.

- God the Holy Spirit appears under Him (emerging from the top of the bottom panel) hovering over the world below.

- And the Mystical Lamb of Revelation (God the Son) stands atop the altar giving His Eucharistic blessing to all believers.

But don’t stop there. At the very bottom of the panel you can see a fountain under which is something that looks like a tap of flowing water issuing forth into a trough that seems actually to run off the bottom of the panel—into the world!

A Latin inscription from the Book of Revelation decorates the front of the fountain (difficult to see here) gives us the key to interpretation: “Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding from the throne of God and of the Lamb” (Rev 22:1).

100 Billion Pixels

100 Billion Pixels

This work of art is almost inexhaustible, so, unfortunately, I cannot do it justice in a relatively short article. I only wish to give you an introduction to it and a resource for further viewing.

When you have a moment, give yourself a treat and take a tour of the altarpiece on the incredible website that the restorers set up to make its beauty available to the world through the marvel of the Internet (click the button below). They digitally photographed every centimeter of the image both before and after the restoration in high resolution, and viewers are able to look at this composite digital image of the Ghent Altarpiece in extreme detail. It is made up of literally 100 billion pixels, which means you can see every intimate detail of the paintings by zooming in.

Click the button below to go to the “Closer to Van Eyck” website. If you just look at the scrolling images without clicking on them, you will see the exquisite colors, contours, and fine details that have been restored to their original form. However, you can also click on any panel and then zoom the image to see the astonishing work that has been done in the restoration.

Actually, if you do so, it will be like looking through the very eyes of Jan Van Eyck as he painted one of the most ravishing gifts to Christ’s kingdom ever created.

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 11/12/23, so it does not end with the regular Soul Work section. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Photo Credits: Photos in the public domain or via Wikimedia Commons: Altaussee Salt Mine; Red turban; Signature; Modern display case; (Renaissance view) Pieter-Frans De Noter; (St Bavo Cathedral) Torsade de Pointes; Details of the altarpiece courtesy of “Closer to Van Eyck: Rediscovering the Ghent Altarpiece”.

[…] don’t forget the famous Ghent Altarpiece by Jan Van Eyck featured angels playing musical instruments to, um, beat the band (notice the harp […]