If I were to ask any high-school-educated person about the Dark Ages, they would probably have heard of the term and think it referred to a period of time after the Fall of the Roman Empire (476 AD) where civilization basically vanished until the Renaissance. In this view, barbarians roamed the world destroying things and Western society as a whole came to a screeching halt.

That is actually a better description of the COVID era in the US than of Europe after the Fall of Rome.

But Rome’s demise was not primarily due to the barbarians, who only put the coup de grâce on the Empire’s incremental decline. It was really the long-term result of the moral and cultural collapse of a once-great civilization.

That is an object lesson for our own times, which I’ll have to leave to another article. My purpose is to talk about what happened after the Fall—and what we’ve been told about it.

Montecassino Abbey, Founded by St. Benedict in 529 AD

Dark History or Dark Propaganda?

One of my favorite historians is Rodney Stark, whose book, The Victory of Reason, lays bare the predominant lie about the “Dark Ages”. (I put the term in quotes for reasons that will become obvious).

Stark says that all of us have been fed a clever, if unquestioned fairy tale about this period in history since we were in grade school. It’s revisionist history at its finest. Here’s how Stark describes it:

For the past two or three centuries, every educated person has known that from the fall of Rome until about the 15th century, Europe was submerged in the “Dark Ages“—centuries of ignorance, superstition, and misery—from which it was suddenly, almost miraculously rescued, first by the Renaissance and then by the Enlightenment.…

But it didn’t happen that way. The idea that Europe fell into the Dark Ages is a hoax originated by antireligious, and bitterly anti-Catholic, 18th century intellectuals, who were determined to assert the cultural superiority of their own time….

Instead, during the so-called Dark Ages, European technology, and science overtook and surpassed the rest of the world! (Victory, p. 35).

I like his frank assessment: “It didn’t happen that way”. As evidence of that, I’ll list below many of the world-transforming accomplishments of the alleged “Dark Ages” and the ways in which that period prepared us for the modern world.

Thankfully, the “Dark Ages” myth has been fully discredited by modern research (i.e., actual facts), which convincingly proves what a remarkable era it truly was, but it is a persistent lie that is hard to overcome in the general perception. A few facts always help.

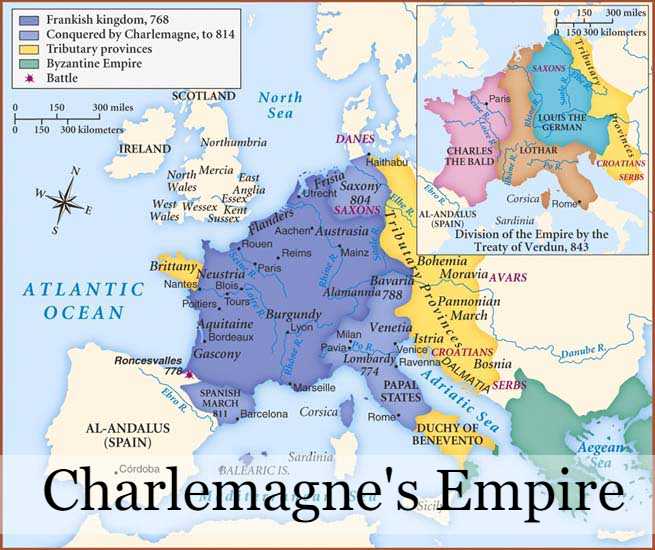

Quick Timeline

What we call the Middle Ages lasted approximately a thousand years (~400-1400 AD), of which the “Dark Ages” were technically the early part (before the Crusades began). It’s more accurate to call this period the “Early Middle Ages”.

What followed were the Crusades, the universities, and the building of the great cathedrals, a period generally called the “High Middle Ages”.

The Renaissance began in the mid-1400s and led to our Modern age. This chart shows a very rough estimate of the time periods, rounding off the numbers for clarity:

(*You know I had to mention Joan of Arc. Basic chronology from Fr. William Slattery.)

But it’s important to note that during the “Dark Ages”, the foundations of what today we call science, education, democracy, and modern capitalism were all laid down by the most unlikely group of movers and shakers in history: Benedictine monks.

For that reason, I think we should call the period a very bright sacred window into divine and human ingenuity. Let’s start with…

Conversions

During those supposedly backward times, millions of souls came to the light of the Christian faith. It was a watershed era for the spread of Christianity as missionaries evangelized the barbarian world and converted whole nations (partial list, see the SW website for further list):

- 509: King Clovis was baptized and the barbarian Franks were converted, sowing the seeds of faith in France;

- 530s: The Vandals (Germanic and Polish tribes) converted to the faith.

- 540s: St. Patrick evangelizes and converts the people of Ireland.

- 570s: The Saxons (western France) converted.

- 580s: The Visigoths (Spain) converted to Catholicism from a heretical sect.

- 590: Pope Gregory the Great sends St. Augustine of Canterbury to convert the Angles (British Isles).

- Late 500s-early 600s: St. Columbanus and his monks take Christianity to northern Italy and central Europe.

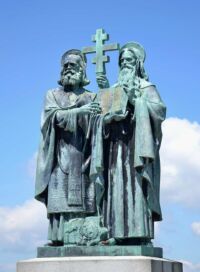

- 700s; St. Boniface evangelized the tribes in the Netherlands and Northern Germany setting the stage for Charlemagne to establish his empire over a Christianized Western Europe in 800.

In Central and Eastern Europe the story is the same, having a somewhat delayed effect due to the ongoing survival of the Eastern Roman Empire (Constantinople) and the battle with the Mongols.

From the late 600s into the Late Middle Ages, the stories of conversions of whole peoples are simply astonishing, along with the ongoing efforts at Christianization of those areas in the West that were already partially converted (partial list):

From the late 600s into the Late Middle Ages, the stories of conversions of whole peoples are simply astonishing, along with the ongoing efforts at Christianization of those areas in the West that were already partially converted (partial list):

- 600s: Missionaries continue their evangelization efforts in England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland.

- 681: Bulgars and Huns convert to Christianity (present-day Bulgaria and Hungary).

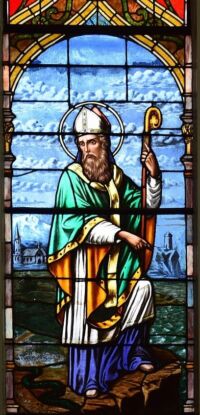

- 800s: The Greek brothers Cyril and Methodius evangelize the Slavic peoples of Central Europe.

- 988: The conversion of the Emperor Vladimir (Russia, Ukraine).

- 997: St. Adalbert evangelizes Prague and what we call the Czech nation today.

- 1000 and beyond: Ongoing evangelization of Scandinavia, as well as the Polish and Germanic peoples.

This is an utterly amazing story of heroism and missionary fervor that rarely gets mentioned in history books. Isn’t it amazing that it all took place in those bad Dark Ages!

The Monasteries

Much of this missionary fervor was brought about by the Benedictine monks, whose monasteries sprang up like mushrooms throughout the Christian world starting from the 500s. [See my earlier article about the Benedictine legacy.]

From these Benedictine monasteries came massive and positive changes in the landscape of Europe and ultimately the world. The vast majority of the human and cultural developments during the Middle Ages came from Benedictine monks and the institutions they established for the good of society (like schools and banks, etc.).

Most importantly, Stark asserts in his book that it was the Catholic work ethic epitomized by monks that gave us these changes.

Medieval Catholics in general believed that the world could be improved beyond the abject misery that the pagan world bequeathed to them, and they set about changing things for the better. What a novel idea.

Not only that, but God gave man stewardship of the earth in the Book of Genesis (2:15; 9:7) which meant that man had a moral duty to investigate and develop the world in order to make it a better place.

Astonishing Developments

So the Catholic monasteries became not only the institutional force for the spread of the Christian faith but also for the advancement of culture as a whole. Those who envision the “Dark Ages” as backward centuries of cultural regression overlook more than a few societal developments that all happened in this period. Let’s consider some of the most astonishing ones.

Agriculture and Technology

In this period, there was not an incremental but an exponential increase in human productivity through several inventions that we take for granted today:

In this period, there was not an incremental but an exponential increase in human productivity through several inventions that we take for granted today:

- The water wheel and watermill for grinding grain—this technology was eventually used for everything from pounding cloth to sawing wood to grinding swords to creating paper. It also made it possible to irrigate fields far and wide by means of pumping stations that had never before existed.

- The invention of the heavy plow made it possible to get under the exhausted surfaces of overused Roman fields and bring up the more fertile soil underneath for planting. It also made it possible to plow up rocky fields without having to extract rocks by hand. Wow.

- Some monasteries became centers of the new science of fish farming, which was quite the important industry for Catholic civilizations that didn’t eat meat on any of the Fridays of the year.

Animals and Transportation

They also upgraded the businesses of animal husbandry and transportation in the same manner. Did you know that Catholic monks developed iron horseshoes (unknown to the Romans) and the big harnesses and collars that allowed horses to travel longer distances and pull heavier loads?

- These improvements in horse technology immensely increased the scope and speed of international commerce.

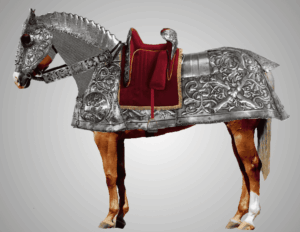

- Advances in saddles, bridles, stirrups, and harnesses made medieval armies more formidable because the powerful “war horse” now became a relevant factor in battles.

- The monks also invented the three-field system of crops, where they rotated two fields (active and fallow) each year and left the third field to grow food to feed the animals—so simple yet so clever!

And you thought monks only made beer and sold fruitcakes at Christmas! Anti-Catholic scholars, of course, conveniently overlooked these and other massive human productivity gains during those terrible “Dark Ages”.

Arts and Science

I don’t have enough time or space to list all the developments that took place in these huge areas of human culture, but I can offer you a summary that I recently saw on the Internet, which listed just a few of the contributions those anonymous medieval monks made to human civilization:

Fire engines, whiskey, the science of genetics, multiple alphabets, musical notation, the scientific method, eyeglasses, the university, double-entry accounting, stained glass, champagne, clocks, cranes, the wheeled plow, heavy armor, soil cultivation, Parmesan cheese (!), algebra, gas lighting, grammar schools and free education, book chapters, the magnifying glass, among many other developments.

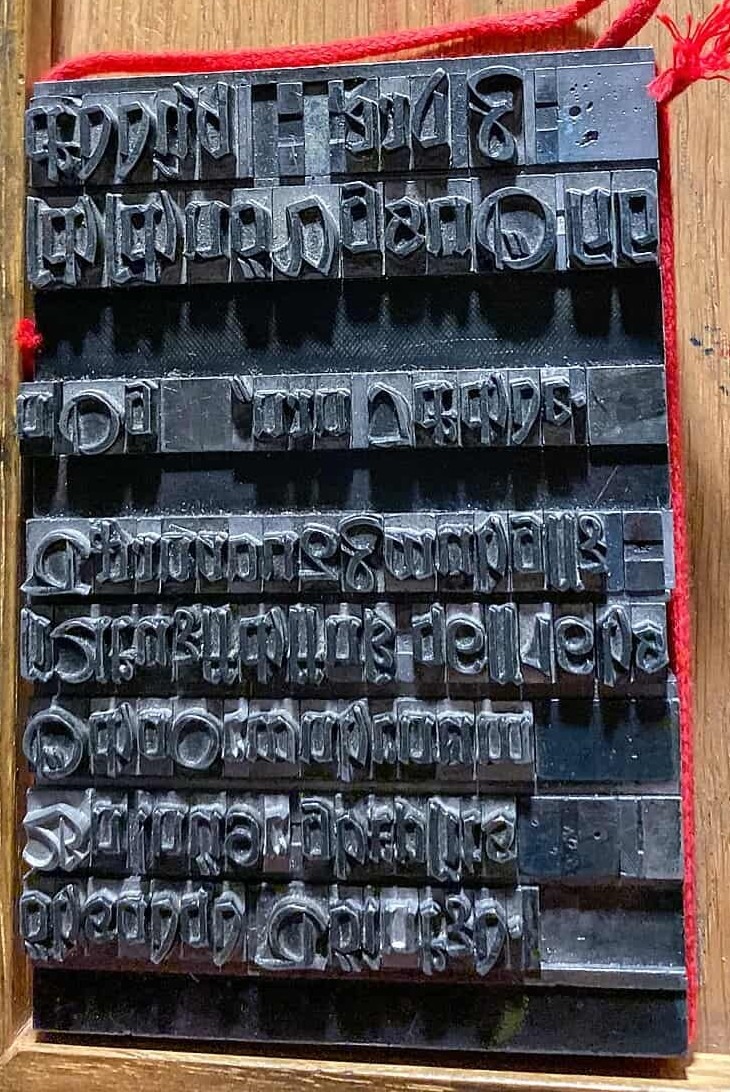

Gutenberg’s printing press (1450) came at the very beginning of the Renaissance era and transformed the world. Please realize, however, that Gutenberg’s invention would not have been possible if multiple centuries of monks hadn’t fostered a literate culture that was also capable of producing a technology like that.

Such a cultural advancement could not have been invented by the technically-backward Asian, Islamic, or African societies of the time.

(Below: Gutenberg’s actual printing press and an early type set.)

I would add to this list other key social developments that were outcroppings of monkish activity but not technically part of a monk’s religious mission. Consider these incredible developments that all came from this period:

- International banks and investment banking.

- Due to the early monastic banks, Europe went from a primitive bartering culture to cash economies to international systems of financing and lending on credit, all within a couple hundred years.

- The international clothing trade and garment industry.

- Significant advancements in construction technologies and techniques, despite not having steel, power instruments,

modern cranes, or bulldozers.

modern cranes, or bulldozers. - Which, of course, is how they built those magnificent cathedrals.

What follows is my favorite satirical meme related to our subject.

Tradition is a Sacred Window

Tradition is a Sacred Window

As you can see, this is a subject that fascinates me from a human and historical point of view, but mostly because it has great relevance for our spiritual lives. It reminds me that, as Catholics, our pilgrimage of life takes place on the crest of the long, flowing river called the Christian Tradition.

This marvelous legacy of Truth, Beauty, and Goodness has handed down to us not only the teachings that save our souls but also the religious culture and many marvelous examples of holiness to emulate. The technological and societal advancements are all icing on the cake compared to the spiritual blessings of such a Tradition.

Now I’m sure you can see why I say that the “Dark Ages” were not dark at all. They were actually a bright sacred window of holiness and human development that gave us virtually everything we have today. Wow.

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 11/16/25. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.

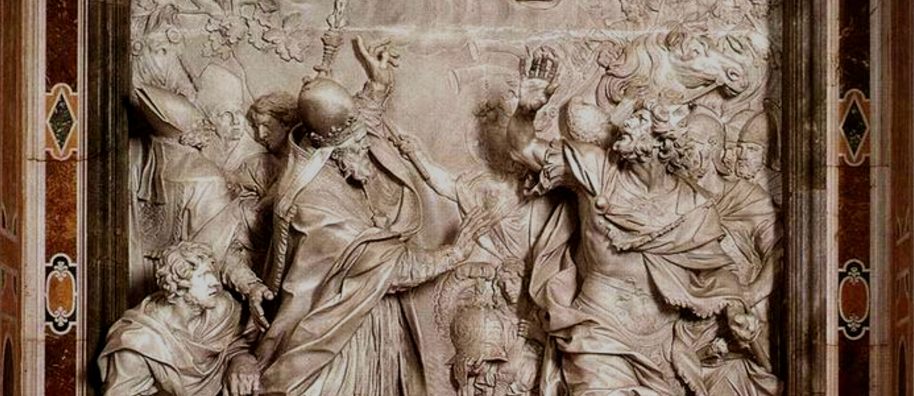

Photo Credits: Feature: “Fuga d’Attila” 1653, by Alessandro Algardi (Pinterest); Monte Cassino Abbey (Ludmiła Pilecka); Charlemagne (Albrecht Dürer, Public domain); King St. Louis IX (JLPC / Wikimedia Commons); St. Patrick (Nheyob); Cyril & Methodius (Pudelek); Norbertine Monastery in Krakow (Jar.ciurus); Windmill (Agnes Monkelbaan); Gutenberg (Printing Press and Type Set): War Horse (Sebacalka).]

Leave A Comment