Most artists do one thing well and focus primarily on that one thing as their avenue to fame and fortune. Renaissance men like Leonardo and Michelangelo may be exceptions to this rule, although each of these had their particular artistic focuses through which they channeled most of their genius. For Michelangelo, that was clearly sculpture. (Leonardo was a genius at everything he did, but his problem was focus. It is said that he left more works undone than he finished!)

French society painter, Jacques Joseph “James” Tissot (1836 –1902), was also an exception to the rule. He had an amazing level of artistic genius that spanned two distinct realms: secular paintings (portrait and scenery) and religious art. There was some overlap between the two realms, but not much until Tissot had a spiritual conversion back to his Catholic faith that caused him to dedicate the last years of his life to painting nothing but religious art. (Please read the story of Tissot’s conversion and full body of religious works here.)

Vibrancy and Dimensions

The 365 watercolor paintings that make up Tissot’s collection, “The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ,” are breathtaking in their detail and in their accurate depictions of the cultural-religious milieu of the Middle East in the late 19th century. Some of his paintings are very vibrant in color but most have a somewhat subdued tone owing to the medium he painted in (gouache, a type of watercolor) as well as the reality of aging. His paintings are well over a century old now, and watercolor doesn’t age as well as oil.

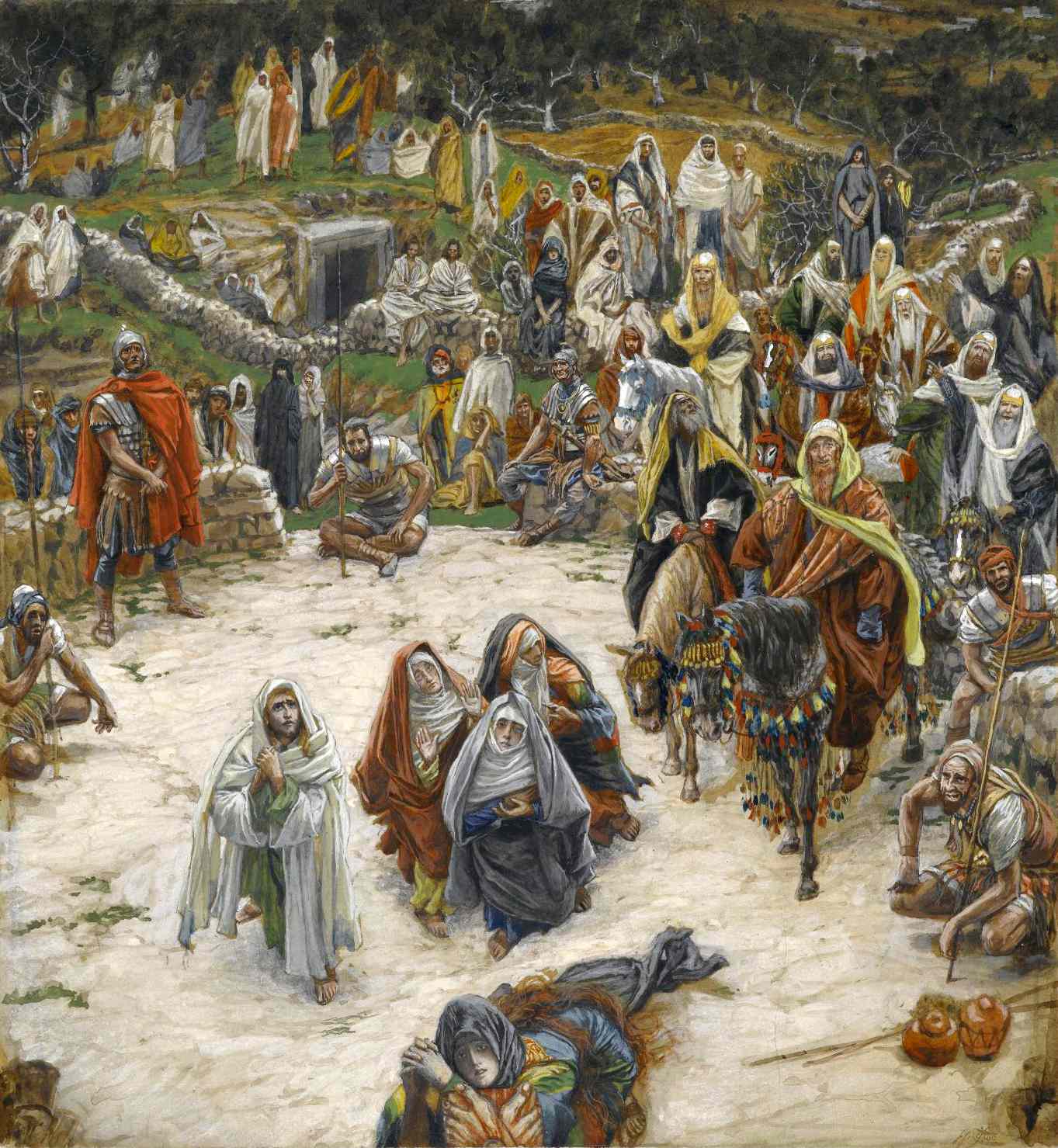

It’s not possible to pick a favorite image out of the hundreds in this collection. They are all unique wonders in themselves. Yet, one stands out as perhaps a summary of Tissot’s style and artistic gifts. The piece entitled “What Our Lord Saw from the Cross” was one of Tissot’s vibrant-color paintings, which makes it a pleasure to view. But more important than its pleasing presentation is its theological astuteness.

At first glance, it appears to be a very large painting, the type that could decorate the whole side wall of a chapel or church. Yet, it is only 9 ¾-inches tall by 9-inches wide, almost a square, and I believe the aspect ratio was carefully chosen by Tissot for what he wanted to convey.

It takes the unique view of Calvary from the vantage point of Christ looking down from the Cross at the people standing around. If the canvas was too tall (portrait mode) he would not have been able to show the full range of characters standing around. If it was too wide (landscape mode), he would not have been able to convince us that it was a view “from above”. The dimensions of the canvas are brilliant and well-chosen.

A View from Above

The very concept of depicting a Crucifixion scene from the Cross is artistic genius at its finest. First let’s have a look at the marvelous painting, and then I’ll offer a few points of perspective about it below.

- Vantage point: High – twelve to fifteen feet above the crowd. The viewer sees what Christ sees from above, looking down. Traditional Crucifixion scenes place the viewer below looking up.

- Feet: Note that the Lord’s crucified feet are visible at the very bottom center of the panel, which would have meant that He was not sloughed over while looking down (if so, we would also see his bent knees in the scene). He is standing straight up – on the nails. The upright position indicates His perfectly voluntary death and His total dominance of the situation. Even in death, He is Lord.

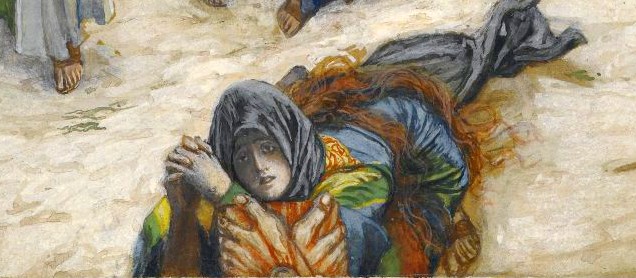

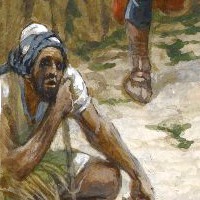

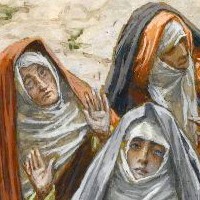

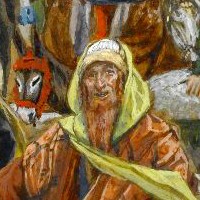

- Range of emotions: Tissot captures the Magdalen’s pleading, the Blessed Virgin’s serenity, the Pharisees’ haughty cynicism, the Centurion’s stoicism, the sneering faces of the uncommitted, and even a few thunderstruck expressions.

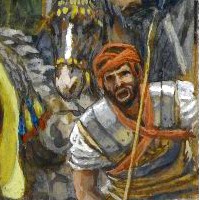

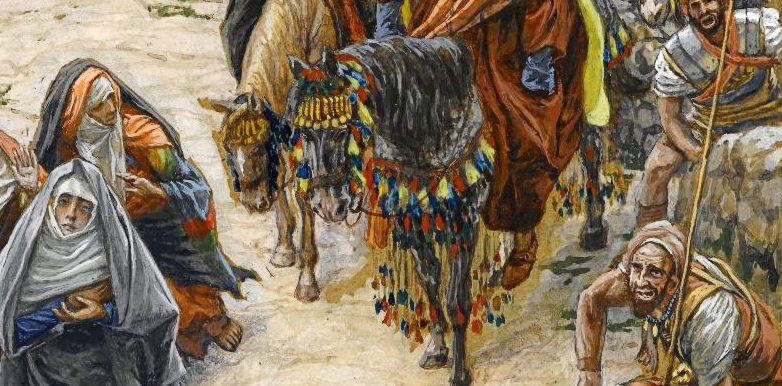

- Horses: Two Pharisees (center right) sit on horses who do not seem to indulge their masters’ arrogance. The humble animals actually bow to the Lord hanging on the Cross. The holy woman next to them seems to marvel at their reverent gestures. Notice also the intricate brocade and tassel work on the finely-adorned creatures.

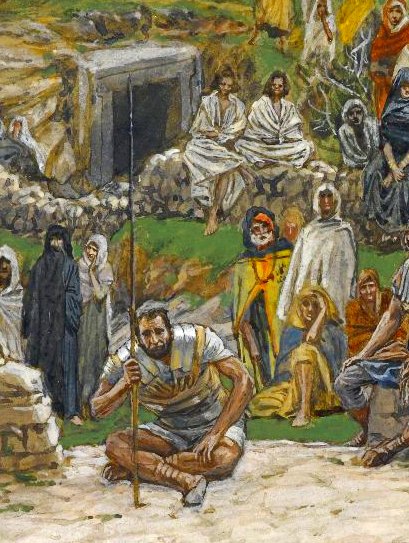

- Low Wall: It goes almost unnoticed, but we can discern a low wall surrounding the summit which creates a distinct separation of spaces between the white stone of Calvary and everything outside. It was Tissot’s way of depicting the inner sanctum of the Crucifixion, like the sanctuary of a church that is cordoned off by the altar rail, only in this case, the Altar is the Cross and Jesus is the High Priest offering the holy sacrifice. It is accurate Eucharistic theology in watercolor.

- Tomb: A soldier with a thin lance (perhaps the one that would eventually pierce His heart) sits slightly left of center stage at the edge of the inner circle; follow his lance upward to where it passes through the dark opening of the empty tomb in the background – a symbol of the ultimate power of death – waiting to swallow its divine prey.

- Disciples: Two men sit next to the tomb. They are, oddly, wearing only sheets. The Gospel of Mark notes only one disciple who was “wearing nothing but a linen cloth about his body” (Mark 14:51), but Tissot’s religious imagination sees this odd scenario as two Apostles who fled the Garden the night before but have come back to witness the Crucifixion. They seem unable to approach the inner circle due to their shame at abandoning the Lord. The sheet symbolizes their shame and covers their “nakedness” of spirit before the Cross.

- This leads us, finally, to the clothing. The vast array of garments, colors, textures, and fashions in this scene is truly amazing. Everyone in this scene is dressed uniquely, some with crude garments, others in armor, and still others with finery fit for a king. We’ve already mentioned the decorations on the horses. The assortment and detail of vesture reflect Tissot’s own background: his father was a maker of fine dresses.

Realism and Invitation

Above all, Tissot’s genius captures a realism about the biblical account of the Crucifixion which could very well reflect the physical reality of the original scene. There is an incredible variety of figures, garments, and facial expressions. We won’t know the actual details until we get to Heaven and are privileged to look in on that eternal mystery with our own eyes.

Still, James Tissot has done us an immense favor by helping us to exercise our religious imagination to wonder what it must have been like to be right there with Him as He looked down – on me, on you – from His high altar.

Soul Work

Tissot’s view is a sacred window into the most sacred event in human history. Like all good art, it invites us into the scene and asks us to look closely at the details. But more importantly, it asks us to place ourselves there and experience the scene very personally. Sit with the imagery and allow it to sink in to your consciousness. Make it your own.

A good spiritual exercise would be to come back to the painting a couple times today or in the next few days. Don’t only analyze it as I have done in this piece, but pray with it. Experience the scene from the two perspectives that Tissot wanted to convey: that of Christ looking down and that of the participants looking up.

Use your imagination to look over the whole human race as Jesus did from the Cross and “survey” sinful humanity. The categories of human reactions to the work of God are all there: haughty rejection (Pharisees), indecisiveness (apostles), growing awareness (some of the men sitting around), humble acceptance (the Magdalene), intelligent meditation (John), and the heights of contemplative prayer (Our Lady).

After you see what He saw, then turn your gaze heavenward like the holy women and men standing around the Cross. Contemplate the scene. Offer the deepest prayer of your heart.

You are standing at the very Center of all grace and truth. Nothing will be denied to the believer.

Thankyou inspiring view I have often wondered the same.Every DAY I know Jesus’s is with me.

[…] Tissot The View from the Cross […]

What a glorious and insightful commentary and call to reflexion and meditation! Many thanks for this. . .

[…] Sacred Windows James Tissot What Our Lord Saw from the […]