If you were a monk in the ancient Church trying to read the Bible, you would have been presented with a real challenge. The early biblical manuscripts (both Greek and Hebrew) had no verses, no chapters, and—incredibly—not even any breaks between paragraphs!

The ancient texts are like one huge run-on sentence that only broke between different books of the Bible.

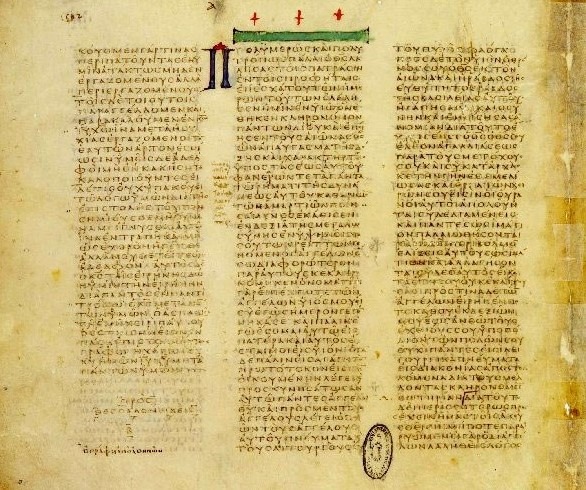

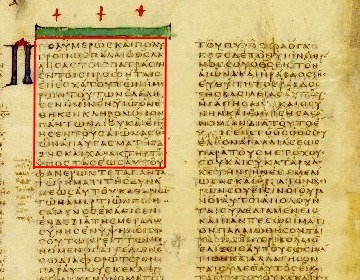

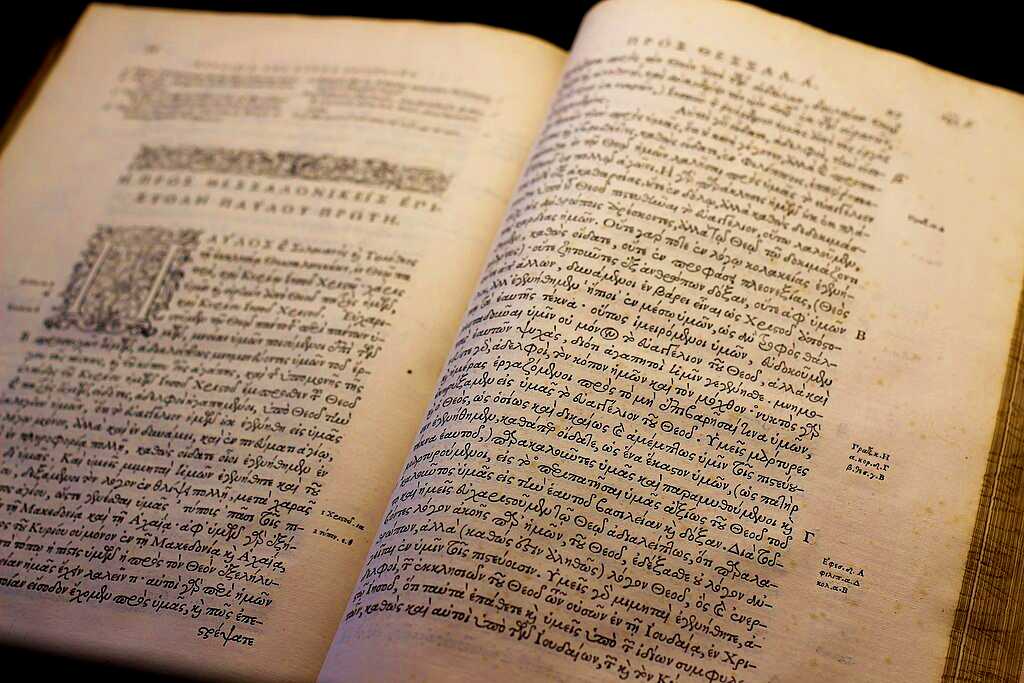

Here what I mean: this is one page in Greek from the ancient Codex Vaticanus (mid-300s AD) which shows the end of Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonians and the beginning of the Letter to the Hebrews (starting after the green line):

Do you hear yourself saying, “It’s all Greek to me?” I do! However, if you look closely at the script, you may also discern a peculiarity even if you don’t know the Greek alphabet. Every letter on the page is a capital letter.

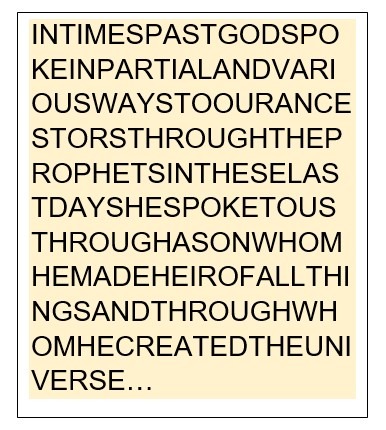

The biblical writers (or at least their scribes) didn’t use small case letters at all, and often times they didn’t even bother with punctuation. The first two verses of the Letter to the Hebrews pictured above would have read something like this:

And so forth. Can you imagine?! It’s a curious thing, isn’t it?

In modern times, when we use ALL CAPITAL LETTERS TO WRITE SOMETHING it has the effect of yelling in print (especially if you put three exclamation points after your pronouncements which I reluctantly admit to doing on social media every so often!!!)

Maybe yelling is what the biblical authors were doing, I don’t know. But they had to get God’s message across to our dull minds somehow.

Anyway, the historical explanation is probably simpler. Writing script in all capital letters was simply the standard method of writing and copying documents in the ancient world. So, they were not yelling…at least I hope not.

Back to our basic point: nowadays, our Bibles are not massive walls of text. They are neatly divided into chapters and verses, so someone in the course of history did us the favor of breaking up all that text into manageable portions.

Stephen Langton

Stephen Langton

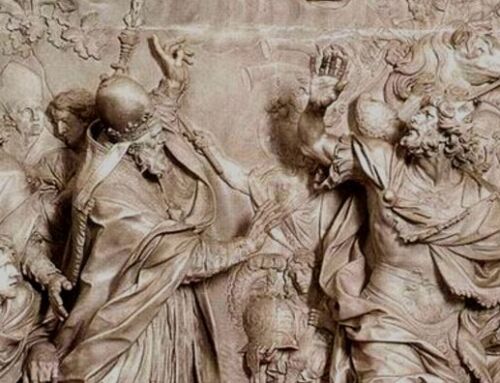

That someone was Stephen Langton (1150-1228) who became the Cardinal Archbishop of Canterbury in 1207 AD and was known as the most scholarly man in England at the time. Langton was quite the mover and shaker of English Catholic history. In addition to being a prolific author, he had one of those dynamic careers that tends to amaze less productive people like me.

He did many things, but he also did three extraordinarily important things that defy belief when you realize that they were all done by one man. For example:

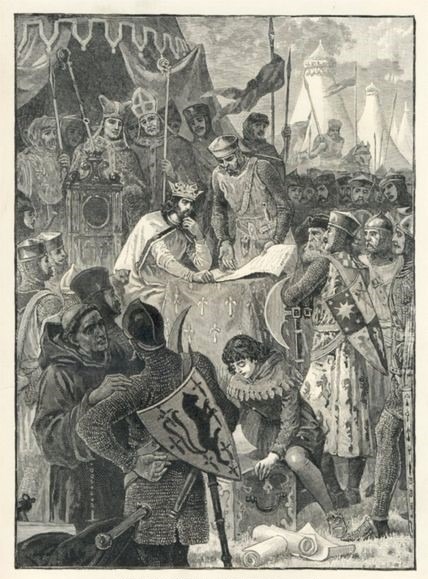

- He led the coalition of English barons who were responsible for forcing King John of England to sign the Magna Carta in 1215 AD. This, of course, is the foundational legal document limiting the power of English kings and the template for all codes of civil rights in the West;

- He is the scholar who divided the entire Bible into chapters.

- He is also credited with composing the Latin hymn, Veni Sancte Spiritus, which the Church sings to this day during the Vigil of Pentecost.

Minor matters, you say? Not quite. They were, in a sense, world-changing things whose effects endure to this day.

In these key areas of faith and society (law, Scripture, liturgy), Langton touches our lives at least indirectly each day. If you read the Bible, or if you enjoy the benefits of the rule of law in our society (at least until the next election), you are feeling some of the long-term effects of the career of this dynamic man.

His Election

The way Langton came to be the Archbishop of Canterbury might not have been the dramatic stuff of a novel like the DaVInci Code, but it certainly is a lesson in medieval church-state politics.

When the previous Archbishop of Canterbury died in 1205 a big fight broke out about who would succeed him. The priests of the Cathedral elected their own man while King John chose his particular candidate and imposed him on the priests of the Cathedral. Being stubborn, the priests rebelled.

A political war ensued between the two factions, so the Pope of the day, Honorius III, called the fighting parties to Rome to explain what was going on. It was a paternalistic effort to resolve a dispute, kind of the way a dad hauls his sons into the kitchen from the yard to stand in front of him and work out their differences!

The end result was that the Pope nullified the elections of both candidates and forced the disputants to go back to the drawing board and do it over, right there in front of him (the meeting took place at the papal residence in Viterbo).

So, before they departed from Italy, they elected a third candidate, Stephen Langton, who then left his teaching post at the University of Paris and returned to Canterbury to take up his new position.

Did I mention that Langton and Pope Honorius were good friends? Funny how that happened. (Hint: they had been classmates in Paris several years before.) As I said: medieval politics. Some things never change. Yet, in this case, it was the best thing the English Church ever did.

King John Signing the Magna Carta, 1215 AD

The Papal Palace at Viterbo, Italy

Chapter Divisions

There is very little historical documentation about when and how Langton divided the Bible into chapters, but it could have been while he was still a teacher at the University of Paris to help him as he was writing his commentaries on the Scriptures. If so, it would have been around 1205 AD.

It could also have been toward the end of his life (ca. 1227 AD) when he had more time to dedicate himself to his studies. Most of the information available on the internet suggest the later date, but both possibilities are plausible.

So, exactly how many chapters are there in the Bible? The total number is 1,334. Here’s the breakdown:

- Old Testament chapters (46 books) = 1074

- New Testament chapters (27 books) = 260

TOTAL: 1,334 chapters.

Imagine painstakingly reading through every single page of the Bible and trying to discern where the best places would be for inserting chapter breaks. It must have taken Langton forever to do all that work!

If I ever meet Langton in heaven I’ll have some questions for him, though, about his decision-making in a few places. In one spot, for example, it looks like he put a chapter division in the middle of a sentence! John’s Gospel, between Chapters 7 and 8 reads like this:

Chapter 7, verse 53 – Then each went to his own house…

Chapter 8, verse 1 – …while Jesus went to the Mount of Olives.

For the life of me, I can’t understand how that happened, but I suspect Langton was imbibing a little too much English mead on the day he was working on the Gospel of John.

Verses Came Later

Anyway, in case you were wondering, the Bible was further divided into verses a little over three hundred years later by a Catholic Frenchman named Robert Estienne, who probably rivaled Langton in diligence and work ethic:

Anyway, in case you were wondering, the Bible was further divided into verses a little over three hundred years later by a Catholic Frenchman named Robert Estienne, who probably rivaled Langton in diligence and work ethic:

- He divided the Greek Bible into verses in 1551.

- He divided the French Bible into verses in 1553.

- He divided the Latin Vulgate (St. Jerome’s version) into verses in 1555.

Here’s the breakdown of verses:

- Old Testament has 27,570 verses (this is based on the New American Bible because the Hebrew, Latin, and Greek versions of the OT are quite different in verse numbering.)

- New Testament has 7,957 verses (this is based on the Greek and Latin versions which are identical in number, but vernacular translations will differ slightly.)

TOTAL verses in the Bible: 33,527—which is preferable to reading 1000 pages of run-on sentences, I would say.

The Sistine Hall of the Vatican Library

Catholic Gifts

Whoever asserted that Catholics are “anti-Bible” was certainly being facetious or possibly downright malicious because men like Jerome, Langton, and Estienne throughout history prove that fable wrong.

Stephen Langton was a scholar and a pastor. His work took place before the Protestant rebellion where the Bible became a sort of weapon to be used against Catholics and other enemies. But the Word of God was never meant to be treated that way.

Langton’s division of the Bible into chapters was not intended to dissect or diminish it, but to make it more accessible to people who wanted to read it and study it. He knew that contact with the Word of God was a source of salvation that unified the Church and sanctified souls.

Of all his accomplishments, that may be his most worthy gift to humanity.

———-

[Note: This article is a reproduction of the Sacred Windows Email Newsletter of 9/08/24. Please visit our Newsletter Archives.]

Photo Credits: Feature and images via Wikimedia: Estienne Greek (ActuaLitté); Langton Statue (Ealdgyth); Viterbo Palace (NikonZ7II); Codex Vaticanus (Public Domain); Estienne Portrait (Rijksmuseum); Anjou Bible (Iannutius de Matrice); Saint-Martial Bible (Bibliothèque nationale de France); Grand Bible of Clairvaux (Public domain); Vatican Library (Vatican Museums); Opening to the Gospel of Matthew (detail), Donald Jackson, Scribe, ©2002 The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, USA. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Thank God for Stephen Langton! Through his hard work he made it so much easier for us today to read the Word of God.

Amen Gary!